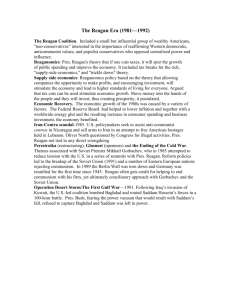

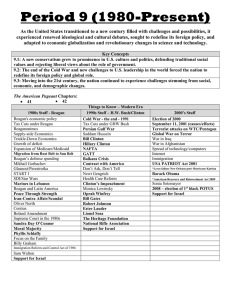

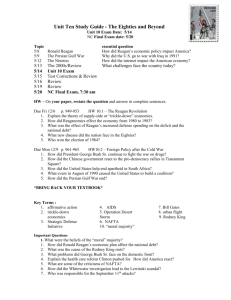

30 Society, Politics, and World Events from Ford to Reagan, 1974–1989 I

advertisement