OCTOBER TERM, 2001 1 Syllabus

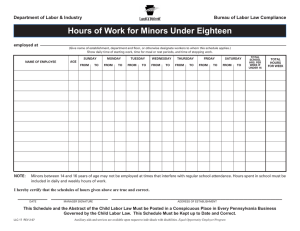

advertisement