No One Cares What Color The Fire Truck Is: A... Interagency Cooperation In Fire Management in Central Oregon

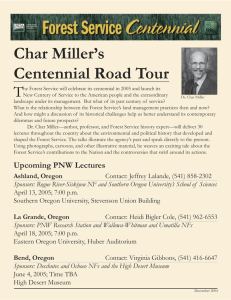

advertisement