The Charles A. Dana Center’s TEXTEAMS Professional Development Model: Evidence for Effectiveness Introduction

advertisement

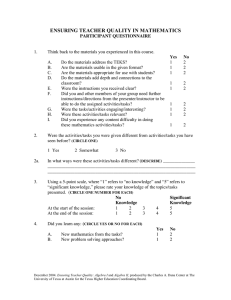

The Charles A. Dana Center’s TEXTEAMS Professional Development Model: Evidence for Effectiveness By Lee Holcombe1 Introduction The No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act of 2001 has increased the profile of scientifically-based research within education and compelled exacting research standards. The act not only requires justification of professional development expenditures with evidence of effectiveness, it also establishes stricter guidelines as to what passes as evidence. Similarly, professional development providers must document the literature upon which their designs are based and offer scientifically-based evidence of design effectiveness. Guided by these mandates, this article profiles the Charles A. Dana Center’s TEXTEAMS professional development model and offers existing evidence that satisfies NCLB criteria for scientifically-based research.2/3 This document comprises three main sections: Standards-Based Education and Effective Reform – The literature clearly establishes that even the best professional development, though critical, cannot sufficiently improve teacher practice and increase student learning unless it is connected to a broader effort. To be effective, professional development must be a component of an aligned system of instructional support mechanisms. Using literature that identifies elements of effective reform in terms of student learning, the Dana Center developed a framework for reform that any district or school can adopt as a decision-making guide. Professional Development – This section identifies characteristics of effective professional development models drawn from recent studies on effective change and relates TEXTEAMS to the characteristics of effective professional development. References – This document is designed to be concise yet sufficiently expository to help guide districts in their decision-making process. However, before making substantial decisions regarding curriculum, assessment or professional development, I encourage readers to consult the listed readings for a deeper understanding of the frameworks. Standards-Based Education and Effective Reform As education reforms evolved into the 1990s, state policymakers built an architecture of standards-based reforms that included academic standards as well as compatible testing, incentive and accountability systems. Among the numerous lessons learned along the way, states found that this architecture was necessary but not sufficient to exact changes in instructional practice (Massell, 1998). States also learned that successful implementation of standards-based accountability systems meant that “virtually all schools, no matter what their demographic characteristics or prior performance, must do different things, not just do the same things differently” (R. Elmore & Fuhrman, 2001). FOOTNOTES: 1. Cynthia Schneider, Darlene Yanez, Laurie Mathis, Gary Floden, and Maggie Myers contributed significantly to this piece through their careful reviews of drafts and valuable input. 2. TEXTEAMS stands for Texas Teachers Empowered in Mathematics and Science. As of February 2003, over 100,000 teachers statewide have attended at least one mathematics or science TEXTEAMS institute. 3. In order to respond to NCLB in the long-term, policymakers, districts and schools will need to gain an understanding of scientifically-based research as well as the ability to recognize it within the entire range of the quality of education research. To this end, we have recently released a separate document entitled Making Sense of Research for Improving Education. An excellent companion to this document, it identifies the various types and qualities of research and how they relate to NCLB, provides examples of each, provides guidance on how to identify and review existing research in ways that are consistent with NCLB, and provides guidance on how to support scientifically-based research. Lee Holcombe has been conducting research and evaluation with the Charles A. Dana Center for approximately one year. Prior to the Dana Center, he conducted research at the Ray Marshall Center at the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas at Austin for four years. His research interests include professional development and school improvement. 34 • Spring 2004 Texas Study Understanding how local educators acquire new knowledge and expertise – commonly referred to as building the capacity of schools to respond to systemic reforms – is the bottom-up counterpart to the top-down policy of standards-based reforms. Without capacity at the local level, state policies have little (or unintended) influence on practice. Massell organizes the response capacity of schools and districts into two broad categories. Organizational capacities refer to the quantity and types of people supporting the classroom, the quantity and quality of interaction within and among organizational levels, material resources, and the allocation of school and district resources. Classroom capacities encompass teachers’ knowledge and skills, curriculum materials, and students’ motivation and readiness to learn. A coherent and robust reform strategy must address all of these determinants of capacity. Standards-based reforms have renewed attention, therefore, on professional development and the supporting policy mechanisms needed to improve instructional practices (Corcoran, 1995; Corcoran, Shields, & Zucker, 1998). The Dana Center has framed an intervention, the TEXTEAMS Instructional Development Model (TIDM), which is based on the TEXTEAMS Professional Development Institutes that encompass both Massell’s organizational- and classroom-level capacities of the district and school. The Dana Center arrived at the TIDM model by triangulating results from the three stud- ies cited in Table 1, each of which provides strong empirical evidence for effectiveness in terms of student outcomes. The TIDM is based on the Instructional Program Coherence (IPC) model developed by Newmann, Smith, Allensworth and Bryk (2001) in their study of student performance on the Iowa Test of Basic Skills (ITBS) in Chicago public schools. The team defined IPC as “a set of interrelated programs for students and staff that are guided by a common framework for curriculum, instruction, assessment, and learning climate and are pursued over a sustained period” (p. 299). They found empirical evidence linking IPC at a school to student ITBS scores in grades two through eight. The researchers employed advanced statistical models using composite measures at each IPC school – arrived at through a common scoring rubric as well as teacher survey data – in 1994 and 1997. Newmann et al. (2001) explicitly required teachers to coordinate the curriculum frameworks both within and across grade levels and/or courses. They also addressed working conditions that support implementation of the framework. Working conditions refers to the degree to which administrators and teachers expect one another to implement the framework, how much the framework drives staff hiring and retention decisions, the extent to which teachers are evaluated and held accountable for the way they implement the instructional framework and pro- Table 1. The left-hand column includes the constituent elements of the TIDM. These elements are based upon the convergence of the three studies listed in the last three columns. A checkmark indicates that the cited research includes the corresponding constituent element. TIDM Teachers of a course use common instructional strategies Newmann et al. (2001) ✔ Just for the Kids (1999) ✔ Holcombe (2002) ✔ Teachers undergo a thorough induction process Course teachers use common assessment strategies ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Teachers across courses coordinate curriculum and assessments ✔ ✔ N/A (Algebra Only) Professional development supports the implementation of the common curriculum, instructional strategies, and assessments ✔ ✔ ✔ Teachers are held accountable for a common instructional framework ✔ ✔ ✔ Teachers are held accountable for student performance on assessments ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Immediate assistance and feedback is provided following teacher observations Instructional specialists provide targeted assistance to teachers and students Collaboration is encouraged Implementation measures are sustained ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Spring 2004 Texas Study • 35 Table 2: Framework of effective professional development practices compiled from selected literature. The last column indicates whether the TEXTEAMS model includes each characteristic. Characteristic of Effective Professional Development Focus on daily activity Active participation Group support and collaboration Focus on assessment aligned with curriculum Focus on content Focus on higher-order thinking skills Sources of Characteristics Murnane and Levy (1996) ✔ ✔ ✔ Elmore et al. (1996) Cohen and Hill (1998) Is it Present in TEXTEAMS? Porter et al. (2000) Desimone (2002) ✔ ✔ fessional development that supports the framework. As with other models, quality professional development in an instructional environment with IPC affects practice and learning when it is sustained over time, provides opportunities for active participation and collaboration, and is aligned with the instructional framework.4 In another study, researchers from Just for the Kids (1999) drew upon their extensive statewide Texas data to identify campuses serving predominately disadvantaged students who sustained high student achievement on TAAS over a three-year period.5 They then conducted in-depth studies of the successful practice of each school to converge on a model for success. As Table 1 indicates, their findings were strikingly similar to those noted by Newmann and his colleagues. Other evidence from Texas includes Holcombe’s (2002) investigation that found positive effects of teacher participation in the Dana Center’s TEXTEAMS Algebra Institute on student learning of Algebra I – as measured by their performance on the Algebra I End-Of-Course Exam – in high schools in San Antonio ISD (SAISD). Holcombe’s findings relate to the TIDM in terms of the context in which teachers from the district participated in the TEXTEAMS Algebra I Institute. Primarily in reaction to low passing rates of its high school algebra students on the Algebra I End-of-Course Exam, SAISD implemented an Algebra Action Plan, the heart of which was the TEXTEAMS Algebra I Institute. As Table 1 suggests, the elements of the Algebra Action Plan are similar to those of the IPC. During the window in which all elements of the Algebra Action Plan were in place, the ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ positive effects of the Algebra I Institute were evident in student performance on the Algebra I End-of-Course Exam. His findings suggest that collaboration and active participation – as measured by the number of teachers at a campus who attend the Algebra I Institute collectively – lead to increased student learning. At SAISD, the effects were strongest among teachers who completed the Institute, but Holcombe also found empirical evidence for the effects of collaboration between those teachers who completed the Algebra I Institute and those who did not at the same campus. Holcombe’s results suggest that concurrent and sustained implementation of all elements of the Algebra Action Plan is necessary to affect student learning. Scores recorded by students of teachers who were exposed to all the elements of the Algebra Action Plan except the Algebra I Institute did not increase as did those of the Algebra I Institute teachers; once the Algebra Action Plan was no longer implemented, scores by students of Algebra I Institute teachers decreased to levels expected had the teachers not completed the institute. Sustainable reform, then, is not a result of a transitional window in which an instructional environment with TIDM elements are achieved and then forgotten. Professional Development Each of the contributing studies on effective change in Table 1 relies heavily on quality professional development. The literature on the importance of professional development in improving the quality of teaching is extensive (Cohen & Hill, 1998; 4. The third dimension of IPC is that schools allocate sufficient resources to advance the instructional framework over time. Of particular note is that the framework, related assessments, and teaching assignments are stable over time. Although they are important, these additional requirements for IPC are not discussed in detail since they are not directly related to professional development. 5. See www.just4kids.org for the report 6. Most research on effective professional development accounts for the context in which the professional development takes place (e.g., coherence of Desimone et al. (2001)). Since the TIDM has already been discussed, those characteristics are not examined here. 36 • Spring 2004 Texas Study Darling-Hammond, 1998; R. F. Elmore, Peterson, & McCarthey, 1996; Murnane & Levy, 1996; Office of Educational Research and Improvement, 1998; Porter, Grant, Desimone, Yoon, & Birman, 2000; Stein, Smith, & Silver, 1999; Weinbaum, 1997; Wenglinsky, 2000). The literature on the essential characteristics of effective professional development is extensive as well. Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of effective professional development in selected notable literature.6 The selection – by no means comprehensive in terms of the body of relevant literature on quality professional development – constitutes characteristics of effective professional development that are common across the literature. The TEXTEAMS Instructional Development Model and Characteristics of Effective Professional Development Table 2 reveals that characteristics of the TEXTEAMS professional development model are consistent with those identified in the literature as effective. In contrast to the one-shot professional development model, the institutes consist of 30 hours focused on particular grade levels and subjects. They are designed to provide teachers “opportunities to learn how to question, analyze, change instruction, and teach challenging content” (Texas Statewide Systemic Initiative, 1998). According to one of the original developers of the TEXTEAMS model, its philosophy is to “instill in teachers an in-depth understanding of the mathematics content and to show how that knowledge translates into classroom practice” (McNemara, 1999). The Dana Center believes that TEXTEAMS models pedagogy that deliberately engenders collaboration and active participation among participants. It situates the teachers in the role of learners as well as instructors, allowing them to experience mathematics and science instruction from the perspective of their students. Having experienced the lessons from multiple perspectives, teachers gain a clearer understanding of the learning process that the lessons are intended to generate. Corcoran, T. B., Shields, P. M., & Zucker, A. A. (1998). Evaluation of NSF’s Statewide Systemic Initiatives (SSI) Program: The SSIs and professional development for teachers. Menlo Park, CA: SRI International. Darling-Hammond, L. (1998). “A conversation with Linda DarlingHammond.” Harvard Education Letter Focus Series (4), 2. Desimone, L., Porter, A. C., Garet, M., Suk Yoon, K., & Birman, B. (2002, Summer). “Effects of professional development on teachers’ instruction: Results from a three-year longitudinal study.” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 24(2), 81–112. Elmore, R. F., & Fuhrman, S. (2001). “Holding schools accountable: Is it working?” Phi Delta Kappan 83(1), 67. Elmore, R. F., Peterson, P. L., & McCarthey, S. J. (1996). Restructuring in the classroom: Teaching, learning, and school organization. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Fennema, E., Carpenter, T.P., Franke, M.L., Levi, L., Jacobs, V., & Empson, B. (1996). “A longitudinal study of learning to use children’s thinking in mathematics instruction.” Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 27(4), 403–434. Goertz, M. E., Floden, R. E., and O’Day, J. (1996). The bumpy road to education reform. CPRE Policy Briefs. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania, Consortium for Policy Research in Education. Hanushek, E. A., Kain, J. F., Rivkin, S. G. (1998). Teachers, schools and academic achievement. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research (Working Paper 6691), 37. Holcombe, L. (2002). Teacher professional development and student learning of algebra: Evidence from Texas. Harvard Graduate School of Education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. Johnson, S. M. (1996). Leading to change, the challenge of the new superintendency. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Inc. Kennedy, M. M. (1998). Form and substance in in-service teacher education. (Research Monograph No. 13). Arlington, VA: National Science Foundation. Massell, D. (1998). “State strategies for building local capacity: Addressing the needs of standards-based reform.” CPRE Policy Briefs. University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia: Consortium for Policy Research in Education. Mayer, D. P. (1997). New teaching standards and old tests: Dangerous mismatch? Harvard Graduate School of Education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard. The emerging consensus on the importance of alignment bodes well for the TIDM. The Dana Center used the Texas mathematics and science curricular frameworks as the benchmark for the development and design of each TEXTEAMS institute, resulting in an alignment between the state curricular content and the investment in teachers’ capacity to effectively deliver the content. Therefore, teachers who participate in TEXTEAMS institutes satisfy the alignment condition for effective standardsbased reforms. McAdams, D., & Houston, R. W. (May 14, 2000). “Give Bush high marks for Texas education successes.” The Houston Chronicle, 4. References Murnane, R. J., & Phillips, B. (1981). “Learning by doing, vintage, and selection: Three pieces of the puzzle relating teaching experience and teaching performance.” Economics of Education 4(1), 453–465. Cohen, D. K., & Hill, H.C. (1998). Instructional policy and classroom performance: The mathematics reform in California, Philadelphia, PA: Consortium for Policy Research in Education, University of Pennsylvania (CPRE RR-39), 48. Corcoran, T. B. (1995). Transforming professional development for teachers: A guide for state policymakers. Washington, DC: National Governor’s Association. McNeil, L. (2000). Contradictions of school reform: Educational costs of standardized testing. New York: Routledge. McNemara, B. (November 2, 1999). Personal interview. Moses, R. P., & Cobb, C. E. (2001). Radical equations: Math literacy and civil rights. Boston: Beacon Press. Murnane, R. J., & Levy, F. (1996). Teaching the new basic skills. New York, NY: The Free Press. National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. (1991). Professional standards for teaching mathematics. Reston, VA: Author. National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. (2000). Principles and standards for school mathematics. Reston, VA: Author. Spring 2004 Texas Study • 37 Newmann, F.M., Smith, B., Allensworth, E., & Bryk, A.S. (2001, Winter). “Instructional program coherence: What it is and why it should guide school improvement policy.” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 23(4), 297–321. Office of Educational Research and Improvement. (1998). Ideas that work: Mathematics professional development. Washington, DC: Eisenhower National Clearinghouse for Mathematics and Science Education, 67. Olson, L. (June 6, 2001). “States turn to end-of-course tests to bolster high school curriculum.” Education Week, 20(39), 1. Porter, A. C., Garet, M. S., Desimone, L., Yoon K. S., and Birman, B. F. (2000). Does professional development change teaching practice? Results from a three-year study. Washington DC: U.S. Department of Education, 68. Resendez, L. (March 12, 2001). Personal interview. Smith, M. S., & O’Day, J. (1991). “Systemic school reform.” In S. H. Fuhrman & B. Malen (Eds.), The politics of curriculum and testing (pp. 233–267). Philadelphia: Falmer Press. Smith, M. S., & O’Day, J. (1993). “Systemic school reform and equity.” In S. H. Fuhrman, (Ed.), Designing coherent education policy: Improving the system. (pp. 250–312). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. 38 • Spring 2004 Texas Study Stein, M. K., Smith, M. S., & Silver, E. A. (1999, Fall). “The development of professional developers: Learning to assist teachers in new settings in new ways.” Harvard Education Review, 69(3), 237–269. Texas Education Agency. (1999). Improving student achievement on the Algebra I End-of-Course Exam. Austin, Texas: Author, 1. Texas Statewide Systemic Initiative. (1998). Texas teachers empowered for achievement in mathematics and science. Austin, Texas: Charles A. Dana Center, The University of Texas at Austin. U.S. Department of Education. (1998). Mathematics equals opportunity. Washington, DC: Author, 30. Weinbaum, A., & Rogers, A. M. (1995). Contextual learning: A critical aspect of school-to-work transition programs. Washington, DC: National Institute for Work and Learning, Academy for Educational Development, 32. Wenglinsky, H. (2000). How teaching matters: Bringing the classroom back into discussions of teacher quality. Princeton: Educational Testing Service, 36. Wilson, S., & Ball, D. (1991). Changing visions and changing practices: Patchworks in learning to teach mathematics for understanding. East Lansing, MI: The National Center for Research on Teacher Education.