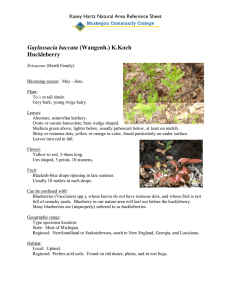

The Federal Trust Responsibility and Treaty Protected Resources on Ceded... Lands: A Huckleberry Case Study

advertisement