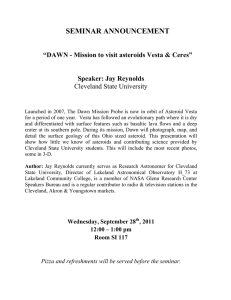

A spectroscopic comparison of HED meteorites and V- Please share

advertisement