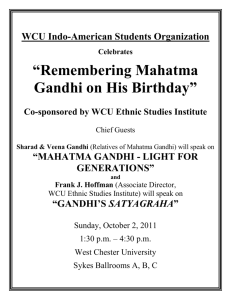

NCERT First Mahatma Gandhi Memorial Lecture – 2007

advertisement