THE HOLOCENE HISTORY OF TAXUS BACCATA (YEW) IN BELGIUM AND... REGIONS Author(s): Koen Deforce and Jan Bastiaens

advertisement

THE HOLOCENE HISTORY OF TAXUS BACCATA (YEW) IN BELGIUM AND NEIGHBOURING

REGIONS

Author(s): Koen Deforce and Jan Bastiaens

Reviewed work(s):

Source: Belgian Journal of Botany, Vol. 140, No. 2 (2007), pp. 222-237

Published by: Royal Botanical Society of Belgium

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20794641 .

Accessed: 10/01/2013 04:53

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

.

Royal Botanical Society of Belgium is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Belgian Journal of Botany.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded on Thu, 10 Jan 2013 04:53:02 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Belg. J. Bot. 140 (2) :222-237 (2007)

? 2007 Royal Botanical Society ofBelgium

THE HOLOCENE HISTORY OF TAXUSBACCATA(YEW)

INBELGIUM AND NEIGHBOURING REGIONS

Koen Deforce*

Flemish

Heritage

Institute, Koning

(*Author

for correspondence;

and Jan Bastiaens

Albert

II-Laan

e-mail:

19 bus 5,

-1210

Brussels,

Belgium

koen.deforce@rwo.vlaanderen.be)

Received 5 September2006; accepted 24November 2006.

?

is limited to

The current natural distribution of Taxus taccata L. inBelgium

a few localities in the southern part of the country. In these localities, Taxus is predominantly

growing on steep, calcareous

slopes, which is believed to be its natural habitat in this part of

Abstract.

In Flanders, the northern part of Belgium, Taxus is considered not to be native and

stands are interpreted there as being planted by humans or as garden escapes. The

data for Taxus, however, show a very different picture

Holocene

pollen and macrofossil

distribution, as well as habitat. It appears that during

regarding abundance and geographical

theworld.

Taxus

the Sub-boreal, Taxus grew in the coastal plain and the lower Scheldt valley, where itwas part

of the carr vegetation on peat. Before the end of the Sub-boreal, Taxus seems to have disap

peared from this region, most probably because of the transition from the carr vegetation to

is not the only case where such observations have been made. In other

(raised) bogs. Belgium

areas of northwestern Europe, Taxus also seems to have had a completely different distribution

and ecology in the past, especially during the Sub-boreal.

An

finds of Taxus taccata

from Belgium

is here given,

of the palaeobotanical

distribution and palaeo

supplemented with finds from neighbouring regions. The Holocene

in a broader northwest European context.

ecology of Taxus taccata are discussed

overview

?

Key words.

Taxus taccata

L., Belgium,

INTRODUCTION

During most of the Pleistocene interglacial

periods, Taxus formed a much more important

element of the vegetation of northwestern Europe

than during theHolocene (Averdieck 1971, God

win 1975, Zagwijn 1992, Lang 1994). Taxus has

been found inBelgium as early as theTiglian-C5

interglacial period (ca. 2-1.8 million yrs BP;

Pleistocene

chronozones according to Lang

1994) (Kasse 1988) and seems to have had its

greatest expansion innorthwesternEurope during

the Holstein interglacial (400 - 367 ka BP), a

Holocene,

vegetation

history, yew.

period characterised by a warm oceanic climate

1962, Kelly

1964,

(Jessen et al 1959, West

Godwin 1975,Watts

1985). High percentages of

both Taxus pollen and macroremains have been

found at several northwest European sites where

Holsteinian sediments are preserved. High per

centages of Taxus pollen have also been found at

several sites inBelgium, in sediments dating from

this period (De Gro?te

1977, Ponniah

1977,

Somm? et al 1978). The most famous palaeo

botanical record of Taxus dating from theHolstein

interglacial, however, is a spear made of Taxus

wood found at Clacton (Essex, UK; Godwin

This content downloaded on Thu, 10 Jan 2013 04:53:02 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

HISTORY OF TAXUS BACCATA INBELGIUM

1975), which is also one of the oldest known arte

factsmade ofwood.

During the last interglacial period before the

Holocene, the Eemian (130 -115 ka BP), Taxus

also played a more important role in the vegeta

tion in northwestern Europe than during the

Holocene, although the pollen percentages are

much lower than during theHolstein interglacial

1975,Woillard

1979,

(Behre 1962, Andersen

Lang 1994). Zagwijn (1983, 1992) even distin

guished a Taxus subzone in his zonation of the

Eemian period in theNetherlands. In Belgium,

both pollen and wood of Taxus have been found

inEemian peat deposits at Be?rnem (De Gro?te

1977, Deforce

1997, Klinck 1999).

During the present interglacial period, the

Holocene, Taxus seems to have played a less

importantrole in the vegetation. However, during

the Sub-boreal (5 000 - 2 500 uncal. BP;

et

Holocene chronozones according toMangerud

was

more

abundant and showed a

al. 1974), Taxus

completely differentdistribution and ecology than

nowadays. The aim of this paper is to review the

available data on the Holocene history of Taxus

and to discuss its past distribution and ecology.

Furthermore, the existing hypotheses for the

Holocene Taxus decline will be evaluated in the

lightof the available palaeobotanical data.

PRESENT-DAYECOLOGY AND

DISTRIBUTION

There is no scientific agreement on the exact

taxonomic position of the genus Taxus, which

encompasses about seven closely related species

scattered throughout the northern temperate

1986, Dempsey & Hook 2000,

region (Voliotis

Thomas & Polward 2003). The species separa

tion within the genus is equally disputed (van

Vuure 1990, Delahunty

2002, Thomas & Pol

wart 2003), although recent genetic research

et al. 2003) shows that the current

(Collins

arewell founded.

delimitations

species

Taxus baccata L. (subsequently referred to

as Taxus), the species native toEurope, is an ever

green needle-leaved gymnosperm shrub or tree,

growing up to 28 m high. The species is slow

223

growing and long-living, reaching maturity only

at ca. 70 years. It is extremely shade tolerant but

can withstand full exposure to the sun (Tutin et

al 1964, Thomas & Polwart 2003). Taxus is

and is

normally dioecious, rarely monoecious

wind-pollinated (Tutin et al 1964, Thomas &

Polward 2003). Itflowers from February toApril

(Richard 1985).

Taxus occurs throughoutmost of Europe and

some parts of northernAfrica, although its distri

bution is very scattered. Taxus thrives best in

regions with a mild, oceanic climate. Its distribu

tion is limited by low temperatures in Scandi

a severe continental climate in eastern

navia,

Europe and aridity and high temperatures in

Turkey and north Africa (Thomas & Polwart

2003). In theMediterranean region, Taxus is con

fined to thehighermountains (Tutin et al 1964).

Taxus does not form pure monospecies

stands (except in theCaucasus Mountains and on

chalk and limestone in England) but belongs to

diverse forest communities mainly composed of

Abies, Fagus, Carpinus, Alnus and Picea (Ellen

berg et al 1991, Jahn 1991, Iszulo & Boratyn

ski 2004).

In Europe, most of the natural stands of

Taxus grow on well-drained calcareous soils,

although the tree can grow on almost any soil,

including silicious soils derived from igneous and

sedimentary rocks (Thomas & Polwart 2003). In

most countries, Taxus is a declining or even

threatened species. The reasons are thought to be

deforestation, selective felling and grazing

1979, Svenning & Mag?rd

1999,

(Muhle

Navys 2000, Holtan 2001, Thomas & Polwart

2003, Mysterud & 0stbye 2004). Several pro

tected areas have been established to conserve the

1991, Hartzell

species (Svalastog & Holand

Kr?l

Brande

1991,

1993,

2002), which also sur

vives in a cultivated form as an ornamental tree in

parks, gardens, and cemeteries (Kr?ssmann

1972, Saintenoy-Simon 2006).

In Belgium, the current natural distribution

of Taxus is limited to a few localities in the south

ern part of the country, namely the southern and

western part of theMeuse district (Fig. 1; Lawal

r?e 1952, Duvigneaud

1965, Galoux

1979, van

Rompaey & Devosalle

This content downloaded on Thu, 10 Jan 2013 04:53:02 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1979, Saintenoy-Simon

224

BELGIAN JOURNALOF BOTANY 140

1983, 2006, Lambinon et al. 1998). At these

localities, Taxus predominantly grows on steep,

calcareous slopes, which are believed to be its

natural habitat in the region (Lambinon et al.

1998). Taxus grows there togetherwith Fagus syl

vatica, Carpinus

betulus, Quercus

robur, Q.

Tilia platyphyllos and, sometimes,

petraea,

Ulmus spp. and Corylus avellana (Duvigneaud

1965, Galoux

1979). In Flanders, the northern

of

part

Belgium, Taxus is considered not to be

native and Taxus stands are interpreted there as

having been planted by humans or as escapes

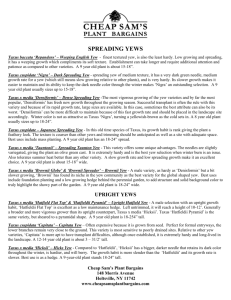

Fig. 1.Map showingboth the currentnaturaldistributionand subfossilfinds of Taxus baccata inBelgium: white

dots denote

tenoy-Simon

natural

& Devosalle

1952, van Rompaey

(data from Lawalr?e

populations

et al. 2006); black symbols denote Holocene

et al. 2006, and Maes

Landuyt

T. baccata

2006, Van

1979, Sain

palaeobotan

ical recordsofpollen, seeds andwood/charcoal ofTaxus. (1)Avekapelle 363 (Baeteman & Verbruggen 1979); (2)

Booitshoeke (Baeteman & Verbruggen 1979); (3) Oudekapelle (Stockmans & Vanhoorne 1954); (4) Sint

inpress); (6) Leffinge

Jacobs-Kapelle (Stockmans & Vanhoorne 1954); (5) Raversijde (Deforce & Bastiaens,

(Baeteman et al. 1981); (7)Wenduine (Mertens 1958); (8) Blankenbergse vaart Zuid (Allemeersch 1991); (9)

Heusden (Stockmans 1945); (10) Laarne - Damvallei (Verbruggen 1971); (11) Borsele (NL)(Van Run 2001);

(12) Ellewoutsdijk (NL)(Van Run 2003, Van Smeerdijk 2003); (13) Baarland (NL)(De Jong 1986); (14)

Terneuzen (Munaut 1967a,b); (15)Waasmunster - Pontrave (Merckx 1996); (16)Weert (Minnaert 1982); (17)

Verrebroek (Deforce et al. 2005); (18) Doel (Minnaert & Verbruggen 1986); (Deforce et al. 2005); (19) Zand

vliet (Munaut 1967a); (20) Oorderen (Munaut 1967a); (21) Kruisschans (Vanhoorne 1951); (22) La Karelsl?

(Waldbillig,easternGutland, Luxembourg) (Pernaud 2001).

This content downloaded on Thu, 10 Jan 2013 04:53:02 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

HISTORY OF TAXUS BACCATA INBELGIUM

from gardens and parks (Lambinon et al. 1998,

Maes et al 2006).

In other parts of northwestern Europe, the

natural distribution of Taxus is also mainly con

fined to soils on limestone and other types of

well-drained, base-rich soils (UK and Ireland:

Tittensor

1980, Kelly & Kirby 1982, Stace

et al. 2002; The Netherlands:

Preston

1997,

et al. 1985; Germany: J?ger & Werner

Weeda

2002; France and Switzerland: Palese & Aeschi

mann 1990; Scandinavia: Jonsell 2000, Moss

berg & Stenberg 2003).

PALAEOBOTANICALRECORDS OF TAXUS

The pollen data

225

were present in the investigated peat sequence.

Similarly, pollen analysis of peat sequences

from Kruisschans

(Antwerp, Belgium; Van

hoorne

(Diksmuide, Bel

1951), Oudekapelle

&

Vanhoorne

Stockmans

1954) and

gium;

(Diksmuide,

Sint-Jacobs-Kapelle

Belgium;

Stockmans & Vanhoorne

1954) did not reveal

Taxus pollen during the palynological research,

while several Taxus seeds were recovered from

the same peat sequences investigated.

Holocene Taxus pollen recordsfrom Belgium and

immediate surroundings

Holocene

records of Taxus pollen from

are

not

very abundant. Out of a total of

Belgium

370 palynological studies from all over Belgium

that were

Characteristics of'Taxus pollen

Taxus pollen is spherical to obtusely angu

its

size ranging between 19.3 and 29.8

lar,

after acetolysis (Averdieck 1971, Beug 2004).

Taxus pollen does not have sacci and is inapertu

rate. The exine is intectate and has a scabrate or

microgemmate sculpturing (Moore et al. 1991,

Beug 2004). Regarding identification, confusion

might be possible with pollen of Juniperus, Pop

ulus, Rhynchospora and Quercus

(Averdieck

et al. 1991, Beug

1971, Zoller

1981, Moore

2004). The pollen grains frequently split and are

to

corrosion

sensitive

1967,

(Havinga

Averdieck

1977,

1971, Rohr & Kilbertus

Taxus

is an

Bradshaw

1978). Although

the

tree,

pollen representation in

anemophilous

surface samples near Taxus stands seems to be

rather low and decreases sharplywith increasing

distance from the Taxus stand (Heim 1970,

Noryskiewicz

2003). These factors, in combina

tionwith the lack of distinctive features such as

sacci, apertures or a distinctive exine sculptur

ing, make it likely that Taxus pollen was not

recognised in some of the earlier palynological

studies (K?ster

1994), or at sites where condi

tions for pollen preservation were poor. During

the palynological

investigation of Wood Fen

et

al 1935), for example, no

Godwin

(Ely, UK;

Taxus pollen was found while several trunks and

even the pollen-bearing cone scales of Taxus

reviewed (Deforce & Bastiaens

2006), only 12 contained substantial records of

Taxus. Sites where Taxus occurred in only one

or a few samples, and with a frequency of less

than 1%, are not included in the overview pre

sented here, as this might represent long-dis

tance transport. On the other hand, itmust be

remembered that in some of the older analyses,

Taxus pollen was very probably overlooked, as

above. Three

additional

already discussed

records derived from the southwestern Nether

lands, close to the Belgian border, are included

in the discussion.

Together, the records show two remarkable

characteristics: (1) they are all situated in the

coastal plain and the lower Scheldt valley (Fig.

1), and (2) they can all be dated from the Sub

boreal. Some of these dates only rely upon bio

zonation as the interpretation of the older dia

grams is not supported by radiocarbon dating. But

still, the available 14C dates (Table 1) allow the

conclusion thatTaxus appears in pollen diagrams

inBelgium and the southernNetherlands between

4750 ? 140 uncal. BP (Oorderen) and 4280 ? 130

uncal. BP (Terneuzen). At all sites Taxus percent

ages remain rather low, varying between 2 and

6%. The percentages are higher only at Zandvliet

(10.1%) and Ellewoutsdijk (16%). Taxus disap

pears from the pollen diagrams between 4035 ?

30 uncal. BP (Raversijde) and 3510 ? 45 uncal.

BP (Baarland)(Table 1).

This content downloaded on Thu, 10 Jan 2013 04:53:02 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BELGIAN JOURNALOF BOTANY 140

226

The seed data

?

\ as

Os Os

_

S

g S

-

VO VO 00

0\

O

<11 <

Q

S

1

1/5

00

S1

ra

-

il

in O

in in

( (

?5?5

O00

"

(

00

- a00sVO- '

S

- Tt

^

5

*

s

(

(

Tjrt

13

? 00

VO^

m m

VO

*, 00

?

>

CP

sI

13

|i

IJ

al

ss

ss

.2<

o U

.s

On

o

o

in o

o

in t^-og o -Ho -H g

,o

-"{ ?T?

- -,, ? 00

PQm co PQm

8

VO ?

iri in

( CN

S 2 s a

m vo ro>

in

t?- as oo oo ??r

o

es ?s m

Tj- r

in in m in 2? in in

( )

VO <r>

<o

vo oo m vo^

oo oo

oo 5

as ^ffl ^i

.2 ?

IS

o p

-H -H

O _ _

ON VOO Or-H

rn

en

^

-H -H g -H -H

O

? O ? O O00 ON^ , oo m

^

CQ

CQ PQ Tj

a

S

? 2

t?

?l

s ?

b? I

Characteristics of Taxus seeds

The seeds of Taxus are highly characteristic:

they are large (6-8 mm) and ellipsoid-ovoid with

a tapering upper end, and rounded to slightly tri

angular or biconvex in section; their surface is

smooth. Seeds cannot be mistaken for any other

species. When fresh, seeds are surrounded by a

conspicuous reddish aril. This aril is the only non

toxic part of Taxus, and it is eaten and digested by

birds and small mammals, while the seed itself

passes the intestinal canal undamaged (Weeda et

al. 1985). Birds are themain agent of seed disper

sal (Zoller

1981, Thomas & Polwart 2003),

which occurs from September into the winter

et al. 2000). As the

1981, Bouman

(Zoller

fleshy aril does not preserve, palaeobotanical

finds of Taxus seeds always lack thatpart.

Holocene Taxus seed recordsfrom Belgium and

immediate surroundings

A small number of Holocene

records of

seeds of Taxus are known from Belgium: subfos

sil seeds have been found atOudekapelle (Stock

mans & Vanhoorne

1954) and Sint-Jacobs

1954), in the

Kapelle (Stockmans & Vanhoorne

western coastal area, and at Kruisschans (Van

hoorne 1951) and Heusden (Stockmans 1945),

both along theriver Scheldt (Fig. 1).

These findsoriginate from the same restricted

region thatyielded subfossil pollen, i.e. the coastal

area and the lower Scheldt valley. The Taxus seeds

have all been recovered from peat deposits, none of

which have been dated by radiocarbon analysis.

Nevertheless, all finds can be attributed to theLate

Atlantic or Sub-boreal on thebasis of theirposition

in the lower part of the so-called surface peat (see

further),or of pollen analysis carried out on the

same peat sequences (Vanhoorne

1945, Van

hoorne 1951, Stockmans & Vanhoorne

1954).

Wood

and charcoal

data

PQ

Characteristics ?/Taxus wood and charcoal

The wood of Taxus is very dense, hard,

elastic and resistant to decay (Zoller

1981). The

This content downloaded on Thu, 10 Jan 2013 04:53:02 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

HISTORY OF TAXUS BACCATA INBELGIUM

sapwood iswhite to yellowish; the heartwood is

red and colours orange-brown after contact with

the air. Owing to its good elasticity, ithas been a

very popular timber for the production of tools

and weapons, in particular bows (Zoller

1981,

Lanting et al 1999, Gale & Cutler

2000).

Taxus wood and charcoal are easy to differentiate

from that of other European gymnosperms, on

account of the distinct spiral thickenings in the

tracheid walls and the absence of resin canals in

the former (Grosser

1977, Schweingr?ber

1990, Gale

& Cutler

2000).

Taxus wood and charcoal recordsfrom

Belgium and immediate surroundings

Holocene

Subfossil Holocene wood remains of Taxus

are only known from Blanken

from Belgium

1991) and Wenduine

berge

(Allemeersch

At

(Mertens 1958).

Blankenberge, Taxus wood

was found embedded in a peat deposit dating

from the lateAtlantic or the Sub-boreal. At Wen

duine, a fragment of Taxus wood was found in an

archaeological site dating from theRoman period

- 402

AD; archaeological periods accord

(57 BC

to

Slechten

2004).

ing

In the southern part of theNetherlands, sub

fossil wood of Taxus has been found at Terneuzen

(Munaut 1967a,b), Borsele (Van Run 2001) and

Ellewoutsdijk (Van Run 2003). At Terneuzen,

several Taxus stems have been recovered from

peat deposits but they have not been dated and

their stratigraphieposition has not been recorded.

However, it is very likely that the stems derive

from the same levels from which Taxus pollen

was recovered, which would place thewood frag

ments in the Sub-boreal (Munaut 1967a, God

win 1968). At Borsele and Ellewoutsdijk, the

Taxus finds were partly preserved in thepeaty soil

and consisted of wooden poles thatwere used as

parts of Roman Age buildings. One Taxus pole

from Borsele was radiocarbon-dated at 4690 ? 60

(several poles made from Pinus

sylvestris gave similar dates) (Sier 2001). The

Taxus poles from Ellewoutsdijk were not dated by

uncal.

BP

radiocarbon analysis but a pole from P. sylvestris

from the same buildings was dated at 4480 ? 25

uncal. BP. The only possible explanation for the

227

time gap between the time of the construction and

themuch older age of part of the construction

wood is that at these sites during Roman times,

subfossil wood was used for the construction of

buildings (Van Rijn 2003). As inferredfrom the

pollen analysis of Ellewoutsdijk (Van Smeerdijk

2003) and the palaeogeographical map of the

1997), these sites

region (Vos & Van Heeringen

were situated in an almost treeless peat-bog envi

ronment during the Roman Age, which might

explain theuse of subfossilmaterial.

The Taxus wood found at theRoman site of

Wenduine (Mertens 1958) has not been dated but

itmight represent subfossil wood too, given that

Wenduine was also situated in a peat bog or a

peri-marine environment during Roman Age

1991, Ervynck et al. 1999).

(Allemeersch

Charcoal from Taxus has been found in La

Karelsl?, eastern Gutland (Luxemburg) (Fig. 1),

in archaeological cave deposits. A few fragments

derive from deposits dating from the Middle

Neolithic (4 500 - 3 500 BC; which corresponds

to the Late Atlantic) while rather large amounts

been recovered from Late Bronze Age

- 800

BC, corresponding to the

deposits (1 100

Late Sub-boreal) (Pernaud 2001). This is rather

surprising as there is no evidence for the exten

sion or even presence of Taxus in any of the

have

palynological records from Luxemburg

(Pernaud 2001), eastern Belgium and theGaume

district (Couteaux

1969a,b), the Plateau des

Tailles area (Mullenders & Knop 1962) or the

French Ardennes (Mullenders

1960, Lefevre et

Holocene

al. 1993).

All dated finds ofHolocene Taxus wood and

charcoal are of Late Atlantic or Sub-boreal age

and, except for the charcoal from Gutland, all

finds were excavated in theBelgian coastal plain

or the Scheldt estuary.

palaeobotanical

records of Taxus

Holocene

from other parts of northwestern europe

Probably one of the earliest mentions of

Taxus occurring in peat deposits was made by

Staring

(1983, re-edition from 1856). The

author expressed his surprise about the presence

of subfossil Taxus wood inDutch peat deposits,

This content downloaded on Thu, 10 Jan 2013 04:53:02 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

228

BELGIAN JOURNALOF BOTANY 140

in contrast with the 19thcentury distribution of

Taxus in The Netherlands and elsewhere in

Europe. That Taxus grew on peat has been further

demonstrated by the finds of subfossil wood at

Ely (UK), described by Miller and Skertchley

(1878) and discussed by Godwin et al (1935).

Another early observation of Taxus trunks recov

ered from peat deposits was made at Ballyfin

Bog (Ireland) by Adams (1905), who stated that

similar finds were so plentiful in former times

that farmers in the neighbourhood used thewood

for gate posts, house roofs, etc.

Firbas (1949) reviewed Holocene records of

Taxus wood from Germany, both from natural

peat deposits and from archaeological contexts

including several trunksfrom peat deposits from

the coastal lowlands of Ostfriesland. Other finds

of Taxus wood recovered from peat deposits in

Germany are listed by Hayen (1960, 1966) and

Averdieck(1971).

Next to these finds of subfossil wood, there

are also numerous pollen diagrams from north

western Europe, showing a distinct Taxus curve,

mostly during the Sub-boreal (for northwestern

1971, 1983, Hayen

Germany, see Averdieck

et al

1960; for Ireland: O'Connell

1988,

et al 1996, Molloy

Mitchell

& O'Connell

for England: Godwin

2004;

1975, Peglar

et al 2004; for

1993a,b, Greig 1996, Batchelor

northwestern France: Van Zeist 1964; for Swe

den: Berglund

1966, for Finland: Sarmaja

Korjonen et al 1991).

DISCUSSION

From theHolocene palaeobotanical records

of Taxus presented, it is clear that this treewas

more abundant and had a different distribution

during the Sub-boreal in northwestern Europe

compared to nowadays.

Taxus occurs sporadically inpollen diagrams

from England (Birks 1982, Godwin 1975), Ire

land (Huang 2002) and Sweden (Berglund

1966) from the Late Boreal or early Atlantic

onwards. For Belgium, the earliest post-glacial

palaeobotanical records of Taxus date from the

late Atlantic or early Sub-boreal. All the other

records from Belgium and the

palaeobotanical

southernNetherlands can be dated from the Sub

boreal as well. Not only in Belgium, but also in

other parts of northwestern Europe (see 3.4),

Taxus shows a maximum in pollen diagrams dur

ing the Sub-boreal.

Distribution

and habitat of Taxus during the

Sub-boreal

Most of the finds of subfossil pollen, seeds

and wood of Taxus inBelgium and the southern

part of theNetherlands are situated in the coastal

lowlands andmore precisely in the area where the

so-called 'surface peat' or 'Holland peat' occurs

in the subsoil. This surface peat was formed dur

ing themid Holocene when the postglacial sea

level rise began to slow down and coastal barriers

could develop (Baeteman

1981, 1999, Vos &

Van Heeringen

These

coastal barriers

1997).

closed the coast almost completely and initiated

mire development. At the time of themaximal

expansion of thepeat, in the Sub-boreal, themires

stretched nearly continuously from Calais

in

northwestern France to southwestern Denmark,

including the coastal plain of Belgium, thewest

ern part of theNetherlands and the lower Scheldt

valley (Pons 1992).

According to Pons (1992), this surface peat

shows more or less the same general development

in the coastal plain inFlanders and the southwest

ern part of theNetherlands. On the saltmarshes of

the regression surface brackish fens developed,

forming Phragmites (Scirpus) peat. Gradually,

d?salinisation and decreasing amounts of avail

able nutrients resulted inCarex-Phragmites fens,

which changed into mesotrophic Betula-Alnus

carr, sometimes with some Pinus. This phase of

carr peat is followed by a transition to Sphagnum

peat and, in most places, the development of

raised bogs resulting in the formation of Sphag

Hwm-Ericaceae peat. Peat growth ended because of

marine transgressions and fluvial sedimentation

between theLate Sub-boreal and theLate Middle

Ages, depending on the location,which resulted in

the covering of the peat with marine and alluvial

1985,

clay deposits (Janssens & Ferguson

Denys & Verbruggen

1989,Allemeersch

1991,

This content downloaded on Thu, 10 Jan 2013 04:53:02 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

HISTORY OF TAXUS BACCATA INBELGIUM

Pons 1992). The upper part of the surface peat is

often lacking as a consequence ofmarine erosion

or medieval and post-medieval peat extraction

et al. 2002, Baeteman

(Baeteman

2005).

Macroremains of Taxus from the coastal plain of

Belgium and the southernNetherlands (Fig. 1),

except those associated with archaeological sites,

have all been recovered from the part correspon

ding to the carr-phase of the peat profiles. They

were associated with seeds and othermacroscopic

remains of plants typical of an alder/birch carr or

fen vegetation composed of, e.g., Alnus glutinosa,

Betula

sp., Comarum

palustre,

Carex

paniculata,

Carex pseudocyperus, Lysimachia vulgaris, Lyco

pus europaeus and Thelypteris palustris (Van

Hoorne

1954,

1951, Stockmans & Vanhoorne

occurrence

in

Allemeersch

of

Taxus

The

1991).

areas

corre

from

these

also

pollen diagrams

sponds with the carr-phase of the analysed peat

1967, Deforce & Basti

profiles (e.g., Munaut

aens inpress).

The fact that, at sites mentioned above,

Taxus was actually part of the local vegetation

community has been ignored or even denied by

several authors as itdoes not seem to correspond

with the present day ecology and distribution of

this tree. Van Smeerdijk (2003: 161-162), for

example, argued that the high percentages of

Taxus pollen at Ellewoutsdijk and Baarland must

be explained by transportby theriver Scheldt and

thus must originate from a more inland area.

However, the fact thatTaxus wood has been dis

covered at Ellewoutsdijk

and at the nearby

Terneuzen, does not support this hypothesis.

Besides, theriver Scheldt followed a more north

ern route at that time and did not flow near Elle

woutsdijk or Baarland (Vos & van Heeringen

1997, Denys & Verbruggen

1989). Many other

records of pollen and macroremains of Taxus

from peat deposits, often in areas without any flu

vial activity, indicate thatTaxus actually did grow

on peat. In fact, this is not an entirely new obser

vation as Godwin already remarked, based on his

research atWood Fen (Ely, UK; Godwin et al.

1935), atWoodwalton Fen (Hunts, UK; Godwin

& Clifford

1938) and on the Taxus finds at

Terneuzen (The Netherlands; Godwin 1968), that

"Taxus almost certainly had an extensive natural

229

occurrence upon peat land, although natural com

munities of this kind can no longer be pointed

out" (Godwin 1968: 737).

Ithas to be stressed here thatpalaeobotanical

data are generally sparse for chalk regions, since

the geological and topographical conditions in

these regions are unsuitable for the formation and

preservation of stratifiedpeat (Tittensor 1980).

This could, of course, bias the reconstruction of

the Holocene

distribution of Taxus presented.

However, this objection may be valid for the

areas with actual natural Taxus populations in

Belgium (Fig. 1) but this is not true for the areas

both to the northwest and to the southeast of this

region. For those areas, Holocene pollen dia

grams and other palaeobotanical data are avail

able, but no Taxus pollen were recorded outside

the coastal area and the lower Scheldt valley, one

exception being the records of Taxus charcoal

from Gutland (Luxembourg).

The Taxus decline

At the above-mentioned sites from Belgium

and surrounding regions, Taxus disappears in the

pollen diagrams during the second half of the

Sub-boreal, around 3 500 uncal. BP (see Table 1).

Similarly, no botanical macroremains of Taxus

have been found that are younger than the end of

the Sub-boreal. In pollen diagrams from other

sites situated in the lowlands of northwestern

Europe, Taxus disappears as well, or shows a

strong decline, before the end of the Sub-boreal.

The Holocene decline of Taxus in northwest

ern Europe is generally attributed to competition

with Fagus and Carpinus, deforestation, selective

1949, Averdieck

felling and grazing (Firbas

1971, Zoller

1981, Svenning & Mag?rd

1999,

Navys 2000, Holtan 2001, Thomas & Polwart

2003). However, these explanations are all based

on the actual ecology and distribution of Taxus,

i.e., Taxus growing on well-drained calcareous

soils. For thedecline of Taxus growing in a fen carr

environment, other explanations must be sought.

The most common explanation for the Sub

boreal Taxus decline

and Carpinus (Firbas

Muhle

1979). Recent

This content downloaded on Thu, 10 Jan 2013 04:53:02 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

is competition with Fagus

1949, Averdieck

1971,

research showed that a

230

BELGIAN JOURNALOF BOTANY 140

Taxus population in Denmark increased after

thinning the tree canopy, especially by felling

beech (Svenntng & Mag?rd

1999). Other

research demonstrated, however, that regenera

tion of Taxus could be rather successful under the

canopies of several broadleaved trees, including

Carpinus betulus (Iszkulo & Boratynski 2004).

Moreover, as Fagus and Carpinus only grow on

well-drained soils (Ellenberg et al 1991), light

competition with these two taxa cannot have

played a role in the decline of Taxus growing in

wet conditions.

Another explanation for the Taxus decline

could be deforestation, but the pollen diagrams

from Belgium and the southernNetherlands do

not indicate deforestation during the period of the

Taxus decline. There are also no indications for

agriculture or other forms of intensive human

impact on the vegetation in the coastal lowlands

during the Sub-boreal (Vos & van Heeringen

1997, Ervynck et al 1999).

Selective felling of Taxus, for its valuable

wood or to avoid cattle poisoning, has been pro

posed as another explanation for the Taxus

decline at several sites in northwestern Europe

et al 1991, Svenning &

(Sarmaja-Korjonen

Mag?rd

& Molloy

O'Connell

1999,

2001).

From theNeolithic onwards, Taxus was probably

themost used wood for themanufacture of bows

et al

1963, Lanting

1999, Beuker

(Clark

other

wooden

2002). Many

implements were

made fromTaxus as well (Godwin 1975, Coles et

al 1978, Gale & Cutler 2000). However, since

human populations and activities were almost

absent during the Sub-boreal, in the region under

consideration here, these explanations can also be

1997, Ervynck

rejected (Vos & van Heeringen

et al 1999, Louwe Kooijmans et al 2005).

In several forests of northwestern Europe, it

has been observed thatTaxus recruitment suffers

from browsing by roe deer, Capreolus capreolus

(Garcia & Obeso 2003, Mysterud & Ostbye

2004). The branchlets, needles and seeds of Taxus

contain a poisonous alkaloid, a lethal toxin for

many species including horses, cows, goats and

humans (Jordan 1964, Schulte

1975). Only a

few animals including roe deer are not sensitive

to it; they like to nibble the yew branchlets and

cause tangible damage to the trees (Mysterud &

0stbye

1995, 2004 Navys 2000). Fully-grown

Taxus trees are largely resistant to the nibbling;

even after a tree is cut down, green shoots appear

from the stump. On the other hand, recent

research has demonstrated that roe deer browsing

reduces Taxus recruitment (Hulme 1996, Garcia

& Obeso 2003, Mysterud & Ostbye 2004). In

general, although roe deer occur inwetland habi

tats (Danilkin

1996, Barancekova

2004), it is

Taxus

that

the

Sub-boreal

decline

very unlikely

can be explained by roe deer -browsing, as there

are no indications for an increase in theirpopula

tion at that time.

One more possible explanation for the Taxus

decline would be a climate change. There is no

evidence, however, for a major change of the cli

matic conditions in northwestern Europe around

3 500 uncal. BP (Davis et al 2003). As Belgium

and the southernNetherlands are not situated near

the limits of the natural distribution of Taxus, it is

unlikely that a minor change in climatic condi

tionswould have caused the Taxus decline.

In conclusion, although some of the above

mentioned explanations for the Taxus decline

might hold true forTaxus stands growing on well

drained, mineral soils or in regions where human

intense (Tittensor

1980,

impact was more

O'Connell

& Molloy

2001), they are not suit

able to explain the Sub-boreal decline of Taxus in

the coastal area of Belgium and the southern

Netherlands. As a more likely explanation for the

decline of Taxus in Belgium and the southern

Netherlands, a change of the environment inwhich

Taxus grew can be proposed. Inmost places in the

coastal area and the Scheldt estuary, this environ

mental change could consist of the already men

tioned transitionfrom the carr peat phase, inwhich

most of the palaeobotanical records of Taxus can

be situated, to ombrotrophic moss peat and, in

most places, thedevelopment of raised bogs result

ing in the formation of Sphagnum-E?ca.ce&e peat

1992, Ver

1986, 1991, Pons

(Allemeersch

bruggen et al 1996, Deforce & Bastiaens

in

the pollen diagrams from

press.). Especially

and Raversijde

Oorderen

1967)

(Munaut

Bastiaens

in

&

show

very clearly

press)

(Deforce

thatTaxus indeed disappears with the transition to

This content downloaded on Thu, 10 Jan 2013 04:53:02 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

HISTORY OF TAXUS BACCATA INBELGIUM 231

ombrotrophic conditions, illustrated by the

increase of Sphagnum and GzZ/ima/Ericaceae.

In the inland part of the lower Scheldt valley,

where no ombrotrophic peat occurs on top of the

fen-carrpeat deposits, the end of the peat growth

was caused by the deposition of alluvial loam and

clay, as a consequence of agricultural practices

(Verbruggen

et al.

1996, Huybrechts

1999).

Allemeersch

1991.

L.,

?

Peat

eastern

in the Belgian

F. (ed.), Wetlands

In: Gullentops

coastal

plain.

in Flanders.

Contributions

zone

ogy of the temperate

to the palaeohydrol

in the last 15 000years.

AardkundigeMededelingen 6, pp. 1-54. Leuven

Press, Leuven.

University

?

Andersen

1975.

The

S.Th.,

Eemian

freshwater

deposit at Egernsund, South Jylland, and the

Eemian

landscape

inDenmark.

development

Dan

marks Geologiske Undersogelse A 1974: 49-70.

Averdieck

CONCLUSIONS

Flora

?

westdeutschland.

peat. This stronglycontrastswith the recent distri

bution and ecology of Taxus, the current natural

distribution of Taxus baccata L. inBelgium being

limited to a few localities in the southernpart of the

country, all situated on steep, calcareous slopes.

The Holocene occurrence of Taxus in the

coastal plain inBelgium, and probably in several

other lowland areas in northwestern Europe, cor

relates with the carr peat phase of the surface or

Holland peat, which was mainly formed during

the Sub-boreal. The decline and disappearance of

Taxus in northern Belgium and the southern

Netherlands during the second half of the Sub

boreal are most likely the result of the transition

of these coastal marshes from a fen-carr environ

ment to ombrotrophic bogs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Averdieck

postglazialen

comments.

1983.

F.-R.,

160:

28-42.

Palynological

investigations

of ten lakes in eastern Holstein,

of the sediments

North Germany. Hydrobiologia

Baeteman

C,

1981.

C,

1999.

?

De Holocene

103: 225-230.

ontwikkeling

van

depositional

his

de westelijke kustvlakte (Belgi?), Ph.D. thesis,

Vrije UniversiteitBr?ssel, Br?ssel, Belgium.

Baeteman

?

The Holocene

toryof the Ijzer Palaeo-valley (westernBelgian

coastal

with

plain)

con

to the factors

reference

trollingthe formationof intercalatedpeat beds.

Geologica Belg 2: 39-72.

Baeteman

2005.

C,

?

How

subsoil morphology

and

erodibilityinfluencetheoriginand patternof late

Holocene

tidal

channels:

case

lowlands.

Quatern.

coastal

Belgian

2146-2162.

Baeteman

C.

&

Verbruggen

studies

from

Sci.

1979.

C,

to the evolution

24:

A

new

?

of the so-called

the

Rev.

approach

in the western

coastal

fessional Paper

167, Belgische Geologische

peat

plain

surface

Pro

of Belgium.

Br?ssel.

Dienst,

Baeteman

Cleveringa

C,

1981. ?

P. &

Het paleomilieu

van Leffinge.

zoutwinningssite

Verbruggen

C,

rond het romeins

Professional

Paper

186,Belgische Geologische Dienst, Br?ssel.

Baeteman

The authorswish to thankNele Van Gemert for

help with the production of the figures and Otto

for valuable

Zur

Geschichte der Eibe (Taxus baccata L.) inNord

All Holocene

records of

palaeobotanical

Taxus from Belgium and the southernNetherlands

show three remarkable characteristics: (1) they all

are situated in the coastal plain and the lower

Scheldt valley, (2) they all date from the Sub

boreal and (3) they all indicate thatTaxus grew on

Brinkkemper

?

1971.

F.-R.,

2002.

Scott

D.B.

& Van

Strydonck

M.,

zone processes

in coastal

at a

Changes

sea-level

stand: a late Holocene

example

C,

?

high

from Belgium.

J. Quatern.

Sci. 17: 547-559.

?

Barancekova

The roe deer diet: Is flood

M., 2004.

plain forestoptimalhabitat?Folia Zool. 53: 285

292.

REFERENCES

Adams

J., 1905.

?

Batchelor

The

occurrence

of yew

in a peat

bog inQueen's County. IrishNaturalist 14: 34.

Allemeersch

L.,

1986.

?

Hochmoortorfe

?stlichen K?stengebiet

Forsch.-Inst.

CR,

Branch

N.,

Elias

S., Hawkins

Shaw P. & Sidell J.,2004.?Middle

Seckenberg

Belgiens.

86:

397-407.

im

Courier

environmental

history

D.

Holocene

of the lower Thames

val

ley.The history of Taxus woodland, pp. 79-80.

QRA International Postgraduate Symposium,

Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences,

Br?ssel,

Belgium.

This content downloaded on Thu, 10 Jan 2013 04:53:02 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BELGIAN JOURNALOF BOTANY 140

232

Behre

?

.-E., 1962.

Pollen-

und diatomeenanalytis

an letztinterglazialen

Kiezel

che Untersuchungen

Davis

Berglund

?

1966.

B.E.,

in eastern

Late-Quaternary

southeastern

Blekinge,

II.

study.

analytical

Opera Bot. 12: 1-190.

?

.-!., 2004.

Leitfaden

pollen

Beug

vegetation

A

Sweden.

Beuker

J.R., 2002.

Nieuwe

?

Drentse

H.J.B.,

1982.

Roudsea

Wood

Birks

der Pollenbestimmung

in het moeras.

Een boogschutter

Volksalm?nak

119: 113-122.

?

Mid-Flandrian

National

forest history of

Cum

Reserve,

Nature

90: 339-354.

bria. NewPhytol.

Bouman

F., Boesewinkel

D., Bregman

?

N. & Oostermeijer

G., 2000.

van

1978. ?Modern

R.H.W.,

Ph.D.

England.

Cambridge,

Brande

A., 2002.

thesis, University

U.K.

?

Internationalen

1-36.

Deforce

history in S.E.

of Cambridge,

Clark

1963.

J.G.D.,

?

Neolithic

and Ireland. Proc.

Collins

D.,

Mill

Prehist.

R.R.

&

44:

Soc.

M?ller

1-45.

M.,

2003.

their reputedhybrids inferredfrom RAPD

cpDNA

Couteaux

M.,

and

,4m. J. Bot. 90: 175-182.

?

Recherches

1969a.

palynologiques

data.

en Gaume,

au pays

d'Arlon,

en Ardenne

m?rid

ionale (Luxembourgbelge) et au Gutland (Grand

Duch? de Luxembourg). Acta Geographica

Lovaniensia,

Leuven,

Couteaux

vol.

Belgium.

1969b.

M.,

9.

Leuven

?

University

Formation

Press,

et chronologie

palynologiques des tufscalcaires du Luxembourg

Ass. Fran?aise

belgo-grand-ducal.

ternaire 3: 179-206.

Danilkin

A.,

1996. ?Behavioural

and European

London.

roe deer.

?tude

du Qua

of Siberian

300 p. Chapman

& Hall,

ecology

In: Cromb?

vol.

ects,

University

De

De

?

T. canaden

of Taxus baccata,

separation

T. cuspidata

and origins of

(Taxaceae)

Species

sis and

1992-2002.

Verbruggen

V.,

?

2005.

L.,

The

gium).

western

Proc.

Soc.

29: 50-98.

Prehist.

Europe.

?

Heal

&

S.V.E.

Orme

The

1978.

B.J.,

J.M.,

use and character of wood

in prehistoric Britain

Noordzeegebied.

Belgi?)

Pollen

Ph.

(ed.),

C.

&

and

The

phytolith

last hunter

gatherer-fishermeninSandy Flanders (NW Bel

England, and theprehistoryof archery in north

Coles

Gelorini

K.,

analyses.

Eibenfre

bows from Somerset,

(Oostende,

Vrydaghs

im polischen

2002. Der

Eibentagung

voor

van 10 jaar opgraven, Arche

Opgravingsverslag

in

6. V.I.O.E.,

Vlaanderen,

Monograf?e

ologie

Br?ssel.

Verspreiding

Eibe-Vorkommen

Inventarisatie

bodemarchief

in het zuidelijke

Raversijde

Tiefland - eine ?bersicht zur Exkursion der 9er

und9.

het

vissersmilieu

represen

?

J., 2006.

Gent,

Pieters M. (ed.), Een laatmiddeleeuws landelijk

Devente

R,

pollen

recent woodland

and

Bastiaens

Gent,

en bescherming,

CAI

II.

2:

35-42.

rapport

VIOE-rapporten

?

Paleob

Deforce

K. & Bastiaens

J., in press.

van

het oppervlakteveen.

In:

onderzoek

otanisch

van zaden: 240 p. KNNV uitgeverij,Utrecht,The

tation factors

thesis, Universiteit

paleo-ecologisch

onderzoek

archeologisch

Netherlands.

Bradshaw

M.Sc.

Be?rnem.

Belgium.

K. &

Deforce

f?rMitteleuropa und angrenzendeGebiete, 542 p.

Pfeil, M?nchen.

data. Quatern.

Sci. Rev. 22:

1701-1716.

pollen

en paleo-ecolo

Deforce

1997. ?Paleobotanisch

K.,

van een Pleistocene

afzetting in

gisch onderzoek

time.

Post-Glacial

Contributers,

from

Europe during theHolocene reconstructed

gurlagernderL?neburgerHeide. Flora 152: 325

370.

J.&

S., Stevenson

A.C., Guiot

?

2003.

The temperature of

Brewer

B.A.S.,

Data

excavation proj

and Doel

Ghent

1, Archaeological

Reports

Press, Gent,

3, pp. 108-126. Academia

Belgium.

Gro?te

V,

?

1977.

van Midden-

Pollenanalytisch

en Boven Pleistocene

Vlaanderen,

Ph.D.

Gent, Belgium.

?

Jong J., 1986.

onderzoek

in

afzettingen

Universiteit

Gent,

thesis,

in verband

Onderzoek

met

het

voorkomen

van Pinus

Baarland.

Rapport 991, Rijks Geologische

Dienst.

De

Verrebroek

Jong

J., 1987.

bepalingen

?

hout

Uitkomsten

in het Hollandveen

van C14-ouderdoms

aan Hollandveen

bij Baarland.

Rap

port 991a, Rijks Geologische Dienst.

Delahunty

of the yew

?

war, and changing

Religion,

an historical

account

and ecological

tree (Taxus baccata L).

Ph.D.

thesis,

J., 2002.

landscapes:

bij

University of Florida,Gainesville, USA.

Dempsey

-

D. & Hook

chemical

I., 2000.

?

Yew

and morphological

(Taxus)

variations.

species

Pharm.

Biol. 38: 274-280.

Denys L. & Verbruggen C, 1989.? A case of

drowning The end of Subatlanticpeat growth

and

related

palaeoenvironmental

changes

in the

lower Scheldt basin (Belgium) based on diatom

and pollen

analysis.

7-36.

This content downloaded on Thu, 10 Jan 2013 04:53:02 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Rev. Palaeobot.

Palyno.

59:

HISTORY OF TAXUS ACCATA INBELGIUM 233

DuviGNEAUD

?

J., 1965.

tion:

le Franc

Un

Bois

H.,

Werner

&

D?ll

H.E.,

Paulissen

Wirth

R,

?

1991.

D.,

erte der Gefasspflanzen

18: 1-122.

V.,

Zeigerw

Scripta

Mitteleuropas.

Baeteman

A.,

hollevoet

?

1999.

sion,

Demiddele

C,

., PlETERS

because

occupation

or the cause of a transgression?

on

the

events

and

human

interaction

H.,

J. et al.,

of a regres

schelvis

M.,

Human

review

und

a

critical

nacheiszeitliche

n?rdlich der

Waldgeschichte Mitteleuropas

Fischer,

Alpen: 256 p. Gustav

R. & Cutler

D., 2000. ?Plants

Gale

?

Garcia

Gilot

neuve.

Studia

Praehistorica

ven, Belgium.

?

., 1968.

Terneuzen

and buried

.

Clifford

post-glacial

history

., 1938.

of British

?

in southern Fenland.

Philos.

229: 323 -406.

Godwin

.,Godwin

M.E.

&

Fen near Ely. J. Ecol.

23: 509-535.

?

Greig

1996.

Great

Britain

J.,

B.E.,

zowa M.

& Wright

Birks

H.E.

England.

Ralska-Jasiewic

H.J.B.,

?

inEurope,

Chichester,

?

Universit?

Bel

L.

baccata

1996.

landscape

develop

in the Connemara

impact

Ireland. J. Biogeogr.

29: 153

?

baccata

i

Holocene

Western

P.E.,

Huybrechts

W.,

sediments

Natural

microsite,

L.):

of yew

regeneration

seed or herbivore

1999.

?

Post-pleniglacial

in central Belgium.

Geologica

29-37.

IszKULO

G.

BoRATYNSKi

&

2004.

A.,

In:

floodplain

Belg.

?

2:

Interaction

between canopy tree species and European yew

J?ger

baccata

Pol.

(Taxaceae).

E.J. & Werner

von Deutschland.

2002.

K,

Band

J. Ecol.

?

52:

523

Exkursionsflora

Kritis

4, Gef??pflanzen:

cher Band 9: 980 p. Rothmaler, Heidelberg Berlin.

Jahn

1991.

G.,

Europe.

perate

Janssens

?

deciduous

Temperate

In: Rohring

E. & Ulrich

deciduous

forests,

pp.

W.

&

Ferguson

D.K.,

forests

.

(eds.),

377-502.

1985.

?

of

Tem

Elsevier,

The

palaeo

ecology of theHolocene sedimentsatKallo, north

(eds.), Palaeoecological

pp. 15-76. Wiley,

Taxus

en

actuelle

Louvain-la-Neuve,

Amsterdam.

eventsduring the last 15 000 years: regional syn

theses of palaeoecological studies of lakes and

mires

Hulme

531.

., 1935.

Untersuchungen

Barlinda

human

and

Uplands,

165.

Taxus

Controlling factors in the formation of fen

deposits, as shownby peat investigationsatWood

Berglund

ment

T. Roy. Soc.

.

Clifford

2002.

C.C.,

of the

gin and stratigraphyof Fenland deposits near

of

Woodwalton, Hunts. II.Origin and stratigraphy

deposits

?

205.

Huang

I. Ori

Studies

vegetation.

Olden

limitation?/.Ecol. 84: 853-861.

forests of the

CambridgeUniversityPress, Cambridge.

Mooren.

la v?g?tation

Ph.D.

thesis,

de Louvain,

2001.

(Taxus

East Anglian fenland.New Phytol. 67: 733-738.

Godwin

., 1975.? The historyof theBritishFlora. A

factual basisfor phytogeography,2ndedn.: 383 p.

.&

occidentale.

D.,

7, Li?ge-Leu

Belgica

thousand

Moreog Romsdal

p? veg ut? Blyttia 59: 197

4-5:

Godwin

Godwin

Holtan

et

r?cents

polliniques

catholique

nurse plants in a threatened tree,

Taxus baccata:

local effects and landscape

level

26: 739-750.

consistency. Ecography

?

Index g?n?ral

des dates Lv. Labora

E., 1997.

toire du

14 de Louvain/Louvain-la

carbone

tree: a

In: Jankuhn H.

Aus

(ed.), Neue

lungst?tigkeit.

inNiedersachsen

und Forschungen

3,

grabungen

Lax, Hildesheim,

pp. 280-307.

August

Germany.

?

entre les spectres

Heim

Les

relations

J., 1970.

gium.

bivore-mediated

Germany.

The yew

zum Verlauf des Niederschlagklimas und seiner

Verkn?pfung mit der menschlichen Sied

Europe

commun

L'if

Ein

Mitteleuropas.

cata

in oldenburgischen

L.)

59: 51-67.

burger Jahrbuch

?

Hayen

1966.

Moorbotanische

H.,

Jena, Germany.

in archaeology:

en Belgique.

Les

113-132.

Belges

?

D. & Obeso

Facilitation

J.R., 2003.

by her

1979.

D.,

Naturalistes

H?lzer

320 p. Hulogosi,

Oregon.

?

1967.

and pollen preser

Palynology

2: 81-98.

vation. Rev. Palaeobot.

Palyno.

?

Hayen

Vorkommen

der Eibe

., 1960.

(Taxus bac

512 p.Westbury Publishing,Kew, U.K.

Galoux

Die

whispers:

Havtnga

A.J.,

geological

in the Belgian

occupation

26: 97-121.

?

Sp?t-

Nordseegebiet

1949.

F.,

?

Remagen,

?

., Jr., 1991.

Hartzell

between

coastal plain during the firstmillennium AD.

Probleme der K?stenforschung im s?dlichen

Firbas

1977.

D.,

Lehratlas: 217 p. Verlag

mikrophotographischer

Naturalistes

Geobot.

Ervynck

Grosser

Dr. Kessel,

Weber

W.

Les

Lompret.

Belges IQ: 441-461.

Ellenberg

de destruc

site menac?

U.K.

Jessen

?

ern Belgium.

Rev. Palaeobot.

Palyno.

S.Th. & Farrington

,Andersen

way,

46:

81-95.

A.,

1959.

The interglacialdeposit near Gort, Co. Gal

Ireland. Proc.

This content downloaded on Thu, 10 Jan 2013 04:53:02 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Roy.

Irish. Acad.

60:

1-77.

BELGIAN JOURNALOF BOTANY 140

234

?

Flora

., 2000.

Polygonaceae.

JoNSELL

aceae

vol

Nordica,

1. Lycopodi

The Bergius

holm.

1964.

Yew

(Taxus

baccata)

poisoning

in pheasants (Phasianus colchicus). Tijdschr.

89:

187-188.

lands over

Klinck

1999.

B.,

J. Life Sei. Roy. Dublin

limestone.

?

De

van

samenstelling

Kr?l

Maes

Belgium.

?

S., 1993.

The

present-day

of yew-tree

reserve

Nienartowicz

(Taxus

A.

&

Yuchola

G.,

396 p. Paul

K?ster H.,

baccata

Boinski

value

1972. ?Handbuch

1994.?

Verwendung

R?VEKAMP

Ch., Van

Inheemse

bomen

en

O., Deforce

K.,

?

P. et ai, 2006.

en

in Nederland

struiken

B.E. & Don

J.,Andersen

S.T., Berglund

?

J.J., 1974.

Quaternary

stratigraphy of Nor

for terminology

and classifica

den, a proposal

tion. Boreas

3: 109-128.

?

van de

Merckx

1996.

V,

Landschapsreconstructie

De

Site Waasmunster-Pontrave.

Gallo-Romeinse

Mangerud

J., De

Duvigneaud

Groothertogdom

Miller

(eds.),

conservation

LWF

in der

and present:

?

S.B.J.,

1878.

601

p. Leach

und

vor-

Bericht

Landesanstalt

G. &

The Fen

and

Son,

Mitchell

F.J.G.,

und

10,

de Belgique.

g?n?rale

170 p. Minist?re

de l'A

griculture JardinBotanique de l'?tat,Bruxelles.

Verbruggen

Belgium.

?

1986.

C,

Palynolo

van een veenprofiel

uit het Doel

gisch onderzoek

van de Archeologische

dok te Doel.

Bijdragen

Dienst Waasland

1: 201-208.

die

f?r

Gent, Gent,

Minnaert

Bradshaw

O'connell

?

1996.

H.J.B.,

R.H.W.,

PlLCHER

M.,

Ireland.

In:

Hannon

J.R. &

G.E.,

watts

Berglund

W.A.,

.E., Birks

M & Wright

Ralska-Jasiewiczowa

events during

(eds.), Palaeoecological

H.E.

the last 15

000 years: regional synthesesofpalaeoecologi

inEurope,

of lakes and mires

cal studies

Wiley, Chichester,U.K.

Molloy

K. & O'Connell

etation

M.,

2004.

?

pp.

Holocene

1-14.

veg

in the karstic envi

dynamics

Ire

of Inis Oirr, Arran

Islands, western

and

ronment

land-use

land: pollen analytical evidence evaluated in the

light of the archaeological

record.

113: 41-64.

42: 7-10.

1:

land past

Archae

naar

1982. ?Palynologisch

onderzoek

G.,

en jysische

van de

oorzaken

antropogene

M.Sc.

thesis,

vorming van het Scheidealluvium.

Quart?re

Vegetationsgeschichte

Methoden

und Ergebnisse:

462 p. Gus

Europas.

tav Fisher, Jena

Stuttgart, Germany.

Lanting

WA.

& van Hinte

J.N.,

B.W., Casparie

?

1999.

the

J. Soc.

Bows

from

Netherlands.

R,

vol.

Skertchley

de Vlaamse

p?riode.

de

Belgium.

?

1994.

G.,

Spermatophytes,

en

Oudenburg

tijdens de Romeinse

39: 5-23.

Minnaert

Coperni

?

Flore

?

Wisbech.

de aangrenzendegebieden (Pteridofytenen Sper

Meise,

matofyten):1091p. Nationale Plantentuin,

Archer-Antiquaries

?

Lawalr?e

1952.

A.,

1958.

ologiaBelg.

S.H. &

M.

L. &

J.-E., Delvosalle

van Belgi?,

Flora

het

en

Luxemburg, Noord-Frankrijk

J., 1998.

J.,

Kustvlakte

Universiteit

Waidenentwicklung

in

Holzes

ihres

Langhe

Aardrijfakunde2: 45-52.

Mertens

in the

L.)

Die Stellung der Eibe

zur Eibe. Bayerische

Beitrage

Walt und Forstwirtschaft.

Lang

J., Brinkkemper

den Bremt

B., Bastiaens

der Nadelgeh?lze:

fr?hgeschichtlicher Zeit,

Lambinon

op

van

of the

Parey, Berlin.

nacheiszeitlichen

in

het bos

condition

natural

forests,

future, pp. 69-78. Nicholas

problems

cus University

,Poland.

Press,

Kr?ssmann

Bakker,

verspreiding, geschiede

Herkenning,

nis en gebruik:

376 p. Boom, Amsterdam.

im

L.

Staropolskie

inWierzchlas. In: Rejewski

Cisy

Wycz?lkowskiego

M.,

P.W.,

Ned

Vlaanderen.

afzettingen

thesis, Universiteit

Gent, Gent,

M.Sc.

population

BrOEKE

?

(eds.), 2005.

842 p. Bert

in de prehistorie:

erland

Soc.

onderzoek

paleoecologisch

van de

houtanalyse

van

basis

van Gijn A.

r?sul

premiers

ner

het laat-Eemiaam.

Be?rnem.

et

Amsterdam.

Philos.

T. Roy. Soc.

247: 533-592.

Birmingham.

?

.& Kirby E.N.,

Kelly

1982.

Irish native wood

3: 181-198.

H. &

Fokkens

and northern Belgium.

Ph.D.

thesis, Vrije Univer

The Netherlands.

siteit, Amsterdam,

?

The Middle

of North

1964.

Pleistocene

M.R.,

Kelly

?

s?dimentaires

la Meuse

(Ardennes,

France):

tats. Quaternaire

4: 17-30.

van

den

louwe

kooijmans

L.P.,

tidal and fluvi

Early-Pleistocene

environments

in the southern Netherlands

atile

environnements

J., 1993.

biologiques ? Holoc?ne dans la plaine alluviale

de

?

Diergeneesk.

?

Kasse

., 1988.

E. & Mouthon

J.,Gilot

des

?volution

Foundation,

The Royal SwedishAcademy of Sciences, Stock

Jordan W.J.,

D., Heim

Lefevre

Moore

P.D., Webb

JA. &

Collinson

Quatern.

M.E.,

1991.

Int.

?

Textbook of pollen analysis, 2nd edn: 216 p.

Blackwell,

Oxford.

This content downloaded on Thu, 10 Jan 2013 04:53:02 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

HISTORY OF TAXUS BACCATA INBELGIUM 23 5

.&

MossBERG

Stenberg

?

2003.

L.,

Den

nya

Peglar

nordiskafloran: 928 p.Wahlstr?m & Widstrand,

Sweden.

Muhle

?

1979.

O.,

von

R?ckgang

Eiben-Waldge

sellschaftenund M?glichkeiten ihrerErhaltung.

In: Wilmanns

T?xen

O. &

R.

von Pflanzengesellschaften,

pp. 483

Vergehen

501. J. Cramer, Vaduz.

?

? l'?tude paly

Mullenders

1960.

Contribution

W,

nologique des tourbi?resde laBar (Departement

Belg. 94: 163-175.

Munaut

A.-V,

Lovaniensia,

Geogr.

Press,

A.V.,

gium.

Pons

A. & 0STBYE

olus

capreolus)

1995.

E.,

A. & 0stbye

olus

E., 2004.

Roe

(Taxus

reserves

Navys E., 2000.?

Roe

deer

(Capre

affects yew

120:

Conserv.

Biol.

and

States

Reimer

Noryskiewicz

A.M.,

tion in the Taxus

?

2003.

Modern

pollen

in theWierzchlas

reserve

O'Connell

M.

& Molloy

Biology

and Environment:

Proc.

IrishAcad. 101B: 99-128.

O'Connell

M.,

Molloy

K.

Post-glacial

landscape

western

with

Ireland

woodland

Kaland

scape

-

and

Farming

dynamics in Ireland during the

woodland

Neolithic.

?

2001.

K.,

history.

P.E. & Moe

past,

&

Bowler

evolution

M.,

present

The

(eds.),

1988.

and future,

pp.

to

land

487-514.

CambridgeUniversityPress, Cambridge.

Palese

R. & Aeschimann

de Gaston

pays

Bonnier.

voisins,

D.,

1990. ?La

France,

vol. 4. Belin,

Suisse,

Paris.

2002.

?

Bard

E.,

et al,

C.J.H.

Bayliss

?

A.,

Int

2004.

de

?

?

a?ropalynologique

sur la

facteurs climatiques

Contribution

des

l'action

floraison de l'orme (Ulmus campestris) et de l'if

(Taxus

R. &

pollen de Taxus

ismes du sol. Nat.

Saintenoy-Simon

et Spores 27: 53-94.

?

du

1977.

G.,

D?gradation

L. par les microorgan

baccata

Pollen

baccata).

Kilbertus

Can.

?

104:

Ben-Ahin

377-382

L'if, Taxus

J., 1983.

27:

(Huy). Dumortiera

J. (with collaboration

Saintenoy-Simon

L.-M.,

Dufr?ne

M.,

baccata

L.,

?

37-38.

of Barbier

Gathoye

Y.,

J.-L.

& Vert?

H.J.B.,

cultural

T.D.,

?

Premi?re

liste des esp?ces

P.), 2006.

et prot?g?es

de la R?gion Wal

rares, menac?es

?

reference

Birks

P., 1985.

Delescaille

in Connemara,

particular

In: Birks H.H.,

D.

Roy.

J.W., Bertrand

l'?tude

Rohr

(north

ernPoland). 16thINQUA Congres,Reno.

& Dines

D.A.

sity Press, Oxford.

P.J., Baillie

M.G.L.,

Richard

for

deposi

Pearman

Cal04 Terrestrialradiocarbonage calibration,26 0 ka BP. Radiocarbon 46: 1029-1058.

itsdistinction fromLithuania. Baltic Forestry 6:

41-46

and con

dynamics

18. Kluwer,

Dor

Geobotany

pp.7-79.

CD.,

Beck

545-548.

reasons

the main

bogs

nutrient

history,

In: Verhoeven

in the Netherlands:

and

(ed.), Fens

in the

formation

New atlas of theBritish and Irishflora. An atlas

of thevascular plants ofBritain, Ireland, theIsle

ofMan and theChannel Islands. OxfordUniver

nature

within

Holocene

peat

of the Netherlands.

drecht.

(Capre

in

baccata

English yew (Taxus baccata L.) in

of Baltic

forests

?

browsing

recruitment

baccata)

inNorway.

parts

servation,

deer

pressure

capreolus)

lower

?

Vegetation,

relation to bilberry(Vacciniummyrtillus)density

and snow depth.WildlifeBiol. 1: 294-253.

Mysterud

1992.

Preston

?

on yew Taxus

feeding

L.J.,

J.T.A.

17: 7-27.

Bodemonderzoek

Pollen

thesis,Vrije Universiteit Br?ssel, Br?ssel, Bel

gisement tourbeuxsitu? ? Terneuzen (Pays Bas).

Berichten van de Rijfadienst voorOudheidkundig

Mysterud

vege

analytic studies of theHol

in the Izenberghe

M.Sc.

area, Belgium.

stenian

d'un

pal?o-?cologique

late-Holocene

10: 219-225.

Archaeobot.

?

J., 1977.

Ponniah

Leuven,

Belgium.

?

1967b.

?tude

and

of laKarelsl? (Waldbillig, easternGutland). Veg.

Recherches

pal?o

etMoyenne

Acta

Belgique.

vol. 6. Leuven

University

en Basse

?cologiques

Munaut

?

1967a.

annual

a year-by

The

laminations.

U.K.

interpreted using recurrent groups of taxa. Veg.

2: 15-28.

Hist. Archaeobot.

?

Pernaud

J.-M., 2001.

history

Postglacial

vegetation

new charcoal data from the cave

in Luxembourg:

Hist.

I.-La

belges.

Soc. Roy. Bot.

dans

les Ardennes

palynologiques

Bull

tourbi?re du Grand Passage.

Ulmus

mid-Holocene

Norfolk,

tationhistoryof Quidenham Mere, Norfolk,UK

et Spores 2: 43-55.

?

1962.

Recherches

C,

Pollen

des Ardennes).

W. & Knop

Mullenders

The

Mere,

year stratigraphy from

Holocene

3: 1-13.

?

Peglar

Mid1993b.

S.M.,

und

(eds.), Werden

at Diss

decline

?

1993a.

S.M.,

grande flore

et

Belgique

lonne (Pt?ridophytes et Spermatophytes).Ver

sioni (7/3/2006), available at http://rnrw.wal

lonie.be/dgrne/sibw/especes/ecologie/plantes/list

aspx?ID=5 94

erouge/fiche2.

Sarmaja-Korjonen

A.,

1991.

?

K., Vasari

Taxus

baccata

Y. & Haeggstr?m

and

influence

C

of Iron

Age man on thevegetation inAland, SW Finland.

Ann. Bot. Fennici

This content downloaded on Thu, 10 Jan 2013 04:53:02 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

28:

143-159.

BELGIAN JOURNALOF BOTANY 140

236

Schulte

1975.

T.,

?

Lethal

tree (Taxus

yew

158.

schweingr?ber

1990.

F.H.,

with

intoxication

Arch.

baccata).

?

leaves

Toxikol.

Anatomy

of

Van

153

34:

?

of European

and Landscape

land.

Sier M.M.,

veen;

een

Borsele,

bewoningsgeschiedenis

in het

opgraving

uit de Romeinse

?

K., 2004.

saurus project.

noemen:

Namen

1,1AP-Rapporten

CAI-rapport

J., Paepe R, Baeteman

C, Beyens

L., Cunat

?

R. et al,

1978.

La formation d'

N., Geeraerts

un nouveau

Herzeele:

stratotype du Pleistoc?ne

main

la

de

Mer

du Nord. Bull. Assoc. Fr.

moyen

Stace C, 1997.? New flora of theBritish Isles: 1165

p. CambridgeUniversityPress, Cambridge.

Nederland.

Stockmans

Deel

1945.

F.,

de

I. Dekker

?

&

Mededel.

Huis,

Wildervank.

Hout.

In: Sier M.M.

(ed.),

een opgraving

in het veen; bewonings

uit de Romeinse

tijd, pp. 51-61.

geschiedenis

d'Heusden-Lez-Gand

Konink.

Rijn

(Bel

Museum

Natuurhist.

F. & Vanhoorne

Konink.

M.

Stuiver

&

R.

Van

Belgium.

Smeerdijk

and revised

CALIB

radiocarbon

calibra

35: 215-230.

?

1991.

Localities

ern part of eastern Norway

J.-C. & Mag?rd

Van

including Aust-Agder.

E.,

and conservation

Biol.

P.A. &

Ecol.

Conserv.

Polwart

Zeist

Taxus

88:

A.,

1980.?

baccata

L.

1999.

tourbi?re

edel.

T.G.,

D.H.,

Heywood

Walters

Population

status of the last natural

173-182.

?

2003.

Taxus

Cambridge.

onderzoek.

Palynologisch

A

91 p.

Stichting

palaeobotanical

Kri

of

study

Biol.

V.H.,

S.M.

& Webb

N.A.,

D.A.,

R,

1951.

alluviale

gique).

Mededel.

Verbruggen

C,

?

Evolution

d'une

Med

21:

tourbi?re

au Kruisschans

Konink.

27:

1971.

geschiedenis

sis, Universiteit

?

de

Bel

(Anvers,

Inst. Natuur

Belg.

1-20.

van Zandig

landschaps

Ph.D.

the

Postglaciale

Vlaanderen.

Gent, Gent,

Belgium.

?

L. & Kiden

P., 1996.

Denys

gium. In: Berglund

Jasiewiczowa

M.

B.E.,

&

Birks

H.J.B.,

Wright

H.E.

Bel

Ralska

(eds.),

Palaeoecological events during the last 15 000

years: regional syntheses of palaeoecological

studies

of lakes and mires

Wiley, Chichester.

Con

D.,

1986.

?

inEurope,

Historical

and

pp. 553-574.

environmental

significanceof theyew (Taxus baccata L.). Israel

Valentine

1964.

(Belgique).

Inst. Natuurwetensch.

Belg.

plaine

Voliotis