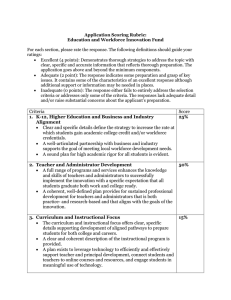

Essential Skill Demand Assessment Business, Administration and Governance Skills

advertisement