Community-Based Participatory Research in American Indian and Alaska Native Communities

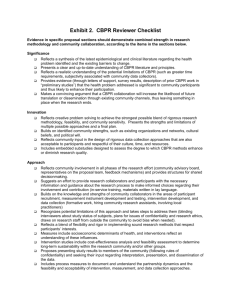

advertisement