AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF

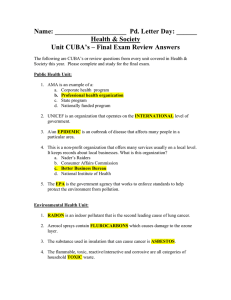

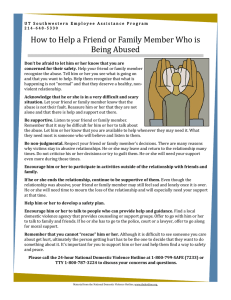

advertisement