Comparative Advantage, Economic Growth, The Gains from Trade and

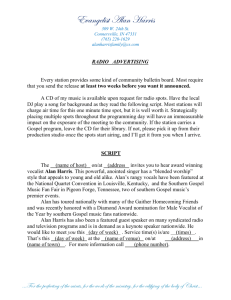

advertisement