Clinical Interventions and Policies for Prevention & Management of Childhood Obesity

advertisement

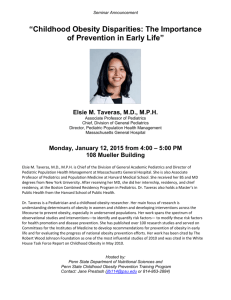

Clinical Interventions and Policies for Prevention & Management of Childhood Obesity Elsie M. Taveras, MD, MPH Assistant Professor of Population Medicine and of Pediatrics, Obesity Prevention Program, Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim g Health Care Institute;; Division of General Pediatrics, Children’s Hospital Boston Academy Health Annual Meeting J June 29, 29 2010 Ove v ew Overview • Prevalence of the childhood obesity epidemic – Early life risk factors – Racial/ethnic disparities • The roles of the health care system and pediatric primary care in obesity prevention and management • Comparative p effectiveness research (CER) ( ) on childhood obesity prevention and management – Evidence-informed policies and recommendations • Accelerating the adoption of childhood obesity CER evidence – Role of Health Information Technology High g Prevalence of Childhood Obesityy in the US P Prevalence l off Childhood Childh d Ob Obesity it (BMI ≥ 95th P Percentile) til ) Boys Aged 2-11 y Girls Aged 2-11 y 30 30 2-5 years 25 25 Percen ntage 6-11 6 11 years 20 20 15 15 10 10 5 5 0 Non Hispanic Non-Hispanic White Non-Hispanic Non Hispanic Black Ogden et al., 2010 Hispanic 0 Non-Hispanic Non Hispanic White Non-Hispanic Non Hispanic Black Hispanic The U.S. Childhood Obesity Epidemic US DHHS, 2001; Hedley et al., 2004; Ogden et al., 2006, 2008 …and in Younger Children Too Prevalence of Obesity in Children Age 2-5 years 16 Perce entage 14 12 NHANES 20012002 Overall in 2007: NHANES 20072008 • 10.4% of children age 2-5 years were obese 10 8 6 21 2% were • 21.2% overweight 4 2 0 Non-Hispanic White Non-Hispanic Black Hispanic Ogden CL, Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Johnson CL. Prevalence and trends in overweight among US children and adolescents, 1999-2004. JAMA. 295:1549-55. 2010. Prevalence of High Weight for Recumbent Length Among US Children From Birth to 2 Years of Age Age, 2007-2008 Ogden, C. L. et al. JAMA 2010;303:242-249. Copyright restrictions may apply. …higher g prevalence in minority y children Prevalence of Severe Obesity, BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2 or 120% off th the age- and d sex-specific ifi 95th percentile til Severe Obesity, Girls Age 2-19 Severe Obesity, Boys Age 2-19 10 9 8 White 10 Black White 9 Hispanics Black 8 Hispanics 7 6.0 66 6.6 6 5 3.9 4 2.8 3 1 1.3 1.8 % % 6 2 6.2 7 3.7 5 33 3.3 4 2.1 3 2.3 2.4 1.6 2 0.9 1 0 0.5 3.0 1.9 01 0.1 0 1976-1980 1988-1994 1999-2006 1976-1980 Wang, Gortmaker, Taveras, IJPO, 2010, in press. 1988-1994 1999-2006 Childhood obesity is of consequence… Ebbeling CB, et al. Lancet. 2002;360:473-482. Evidence-Based Targets of Behavioral C Counseling li – Prenatal P t l to t Early E l Childhood Childh d • Gestational weight gain (Oken, (Oken Taveras et al. 2006) • Maternal smoking during pregnancy (Oken, Taveras et al. 2006) • Rapid infant weight gain et al. 2009) (Taveras • Breastfeeding promotion (Taveras et al. 2005) • Sleep duration and quality (Taveras et al. 2008) • Television viewing (Taveras et al. 2007) & TV sets in bedrooms • Improved responsiveness to infant hunger and satiety cues (Hodges and Fisher, 2008) • Parental feeding practices, eating in the absence of hunger (Taveras, (Taveras 2006 2006, Fisher and Birch Birch, 1998 & 2009) • Portion sizes ((Fisher et al. 2008)) • Fast food intake (Taveras et al. 2006) • Sugar-sweetened beverages • Physical activity participation • Racial/ethnic differences exist in almost all known, early life risk factors for childhood obesity Taveras, et al. Pediatrics; 2010 Summary • The childhood obesity epidemic spares no age group, is of consequence, and disproportionately affects racial/ethnic minority children • Prevention must start early – S Search h ffor modifiable difi bl d determinants t i t att early l stages t off h human development • Prenatal • Infancy • Early childhood – Examine earlyy origins g of racial/ethnic differences in risk factors • Need for preventive interventions based on the b t available best il bl evidence id Where do we start? …and how does health care fit in? Mezzo-level: Role of the Health Care System y • Support patient selfself management • Provide clinician training on evidence-informed practices for decision pp support • Track clinician performance on obesityrelated l t d dimensions di i off care • Use effective clinical information systems to track patient progress Chronic Care Model, Wagner et al. • Provide adequate reimbursement for obesityrelated services High g Five for Kids! Improving Primary Care to Prevent Childhood Obesity Obesit Joint project of DACP, Harvard School of Public Health, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Funded by NIH (PI: Gillman) High Five for Kids S d Design Study i • Cluster RCT in 10 pediatric primary care practices – – • Children age 2-6.9 years old at elevated risk – – • 5 iintervention t ti sites it 5 usual care BMI >95th %ile or 85th-95th %ile if at least one parent overweight 12-month intensive intervention – Followed by 12 12-month month maintenance maintenance, follow-up follow up Motivational Interviewing First Steps for Mommy & Me Main i Intervention i Components C 1 Pediatricians’ endorsement of mother-infant 1. mother infant behavior change using brief focused negotiation 2. Individualized coaching using motivational interviewingg byy a studyy health educator 3. Matching parent counseling and educational materials to child’s developmental stage 4 Focus 4. F on evidence-based id b d behaviors b h i 5 Group meetings to reinforce content and promote 5. peer support and social networking Micro-level: Role of Pediatric Primaryy Care • The primary care setting offers unique opportunities to intervene for children at risk for obesity and its complications. complications • Regular visits during childhood allow both detection of elevated BMI levels and offer opportunities for prevention and treatment. • The continuity of the pediatrician/family relationship, embodied b di d in i the h concept off the h “medical “ di l home,” h ” has h been associated with increased parental satisfaction, particularly i l l on measures off patient-doctor i d communication. Role of Pediatric Primary Care • Institute of Medicine recommends that child health professionals routinely: – Monitor and track BMI g and – Offer evidence-based counseling guidance to improve nutrition, increase physical activity, and decrease sedentary b h i behaviors Preventing Childhood Obesity: Health in the Balance. Institute of Medicine Committee on Prevention of Obesity in Children and Adolescents, 2005 Comparative Effectiveness Research (CER) • CER compares the th risks i k andd benefits b fit off different diff t interventions and strategies for preventing, diagnosing, treating, and monitoring health conditions under real world conditions. • Dissemination of this evidence can help achieve improved patient care by allowing individuals, clinicians,, and policymakers p y to make informed decisions. topic in part because of • Obesity is a high priority CER topic, the high prevalence among children, its associated comorbidities, and the need for testing of available prevention i andd treatment strategies. i United States Preventive Services Task F Force (USPSTF) • In February b 2010, the h USPSTF updated d d their h i evidence-based recommendations on screening and management of obesity in children. • New recommendations: d i – sufficient evidence to recommend that clinicians screen children ≥ 6 years of age for obesity using BMI, and – offer them comprehensive, intensive behavioral interventions to promote improvement in weight status. t t Systematic y Review for USPSTF • Whitlock, Whitlock et al. al Pediatrics, Pediatrics 2010 – Reviewed 15 good-quality weight management interventions among children 4 to 18 years of age – No published studies targeted children < 4 years – Comprehensive, behavioral interventions of medium-high intensity were the most behavioral approach for management – Two medications (orlistat and sibutramine) combined with behavioral interventions resulted in small or moderate BMI reduction d i in i obese b adolescents d l on active i medication di i – “Available research supports at least short-term benefits of comprehensive h i mediumdi to high-intensity hi h i i behavioral b h i l interventions in obese children and adolescents.” Evidence-Informed Recommendations on Childh d Ob Childhood Obesity it Management M t 1 Expert Committee Recommendations on the 1. Assessment, Prevention, and Treatment of Child and g and Obesity. y Adolescent Overweight 2. National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) measures on improving quality in childhood obesity care. 3 White House Task Force Report on Childhood 3. Obesity • Recommendations from the American Academy of Pediatrics 4 Coming Soon – Institute Of Medicine Report on 4. Obesity Prevention Policies for Young Children Expert Committee Recommendations • In 2005, 2005 the AMA AMA, HRSA HRSA, and the CDC CDC, convened an expert committee to develop recommendations on the assessment, prevention, and treatment of childhood overweight i ht andd obesity. b it Pediatrics, P di i December, D b 2007 • For all children 22-17 17 years of age, the recommendations include: – Assessment of BMI and specific p nutrition and physical p y activityy counseling. – Methods to screen obese children for current medical co-morbidities. co morbidities – Propose 4 stages of care; the first is brief counselingg that can be delivered in pediatric p primary care, and subsequent stages for structured weight management. National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) HEDIS Measures • IIn 2009 2009, the h NCQA released l d Health H l h Plan Pl andd Employer E l Data D and Information Set [HEDIS] measures related to childhood obesity. y • The new measures assess how consistently physicians perform BMI percentile assessments and document nutrition and physical activity counseling among children. • HEDIS is a tool used by more than 90% of U.S. health plans to measure performance on important dimensions of care. • The new HEDIS measures are expected to foster benchmarking and quality improvement in the area of childhood obesity assessment and management. White House Task Force Report on Childhood Obesity American Academy of Pediatrics • AAP pledged in February 2010 to engage in a range of efforts to achieve two primary goals: – Calculate BMI for every child at every well-child visit beginning at age 2, and provide information to parents about how to help their child achieve a healthy weight. weight – Provide “prescriptions” for healthy active living, including good nutrition and physical activity, at every well-child visit, along with information for families about the impact of healthy eating habits and regular physical activity on overall health. – www.aap.org/obesity/whitehouse / b it / hit h Institute of Medicine Report • IOM Committee on Childhood Obesity Prevention Policies for Young g Children statement of task: – Review factors related to overweight and obesity in infants, toddlers, and preschool children (birth-5 years) and make recommendations on early childhood obesity prevention policies. • Final report in 2011 Accelerating the adoption of childhood obesity b it CER evidence id by b clinicians li i i • Role R l off Health H l h Information I f i Technology T h l (HIT) – Use of HIT, such as electronic medical records (EMRs), offers potential to accelerate the adoption p of childhood obesity y CER evidence. – Innovative strategies that take advantage of this new technology will be used to assess and improve quality of care • In pediatric outpatient settings, EMR-based decision support has already been shown to improve prescribing patterns, increase immunization rates, rates improve delivery of preventive asthma care, care and improve documentation of obesity counseling. • More research needed on design features that may enhance pediatrician perception of usability and efficiency Accelerating the adoption of childhood obesity b it CER evidence id by b parents t • HIT strategies i may be b especially i ll effective ff i if augmented by outreach and support to patients and families. families • A variety of patient-outreach patient outreach strategies could be effective in improving quality of care, but remain g understudied including: – Direct-to-patient or parent communications e.g. mailings. • In a school-based setting, DTP communications about children’s BMI screening was screening, as an informative, informati e motivational moti ational tool for parents and resulted in improvement in family diet and activity. – Patient web-based portals to enhance physician-parent communication. Improving the Quality of Pediatric Obesity Care through the use of H lth Information Health I f ti Technology T h l Elsie M. M Taveras, Ta eras MD, MD MPH Obesity Prevention Program, Harvard Medical School and Harvard d Pilgrim il i Health l h Care C American Diabetes Association Grant Study Design • Conduct a cluster RCT in 14 pediatric ppractices to examine the extent to which direct-to-parent communications and decision alerts to clinicians can increase BMI screening, BP monitoring, obesity diagnosis, provision i i off counseling li among all ll children hild 2-17 years of age Overarching framework for improving quality of pediatric obesity care: The Chronic Care Model HIT interventions Direct-toParent communications? Conclusions Whatt are Promising Wh P i i Clinical Cli i l Strategies St t i for o Childhood C d ood Obes Obesity y Management? a age e ? 1. Focus on evidence-informed targets & recommendations 2. Start intervening early – early life risk factors and racial/ethnic disparities call for an earlier focus • “Racial and ethnic differences in obesity may be partly explained by differences in risk factors during the prenatal pperiod and early y life.” – White House,, 2010 3. Multi-level changes likely to be most effective for sustainable changes in the health care system, e.g. chronic care model Whatt are Promising Wh P i i Clinical Cli i l Strategies St t i for o Childhood C d ood Obes Obesity y Management? a age e ? 4. Use of behavior change approaches grounded in theory, e.g. stages of change, motivational interviewing 5. Health information technology (HIT) offers potential i l for f accelerating l i the h adoption d i off childhood obesityy CER evidence