NIMH Practical Trials: Implications for Practice and Policy Matthew V. Rudorfer, M.D.

advertisement

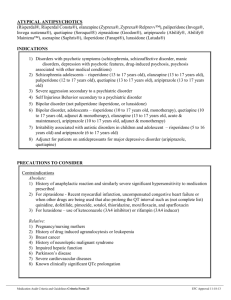

NIMH Practical Trials: Implications for Practice and Policy Matthew V. Rudorfer, M.D. Division of Services & Intervention Research National Institute of Mental Health June 5, 2007 Two Kinds of Translational Research Bench Bedside Pathophysiology Diagnostic tests Biomarkers New treatments Practice Practical Trials Clinical Trials Networks Services Research Dissemination & Implementation Utility of Large Studies – “Practical Clinical Trials” • Public health perspective on clinical issues – Big questions and community effect – Chronic diseases require long term look • Longitudinal follow-up and link intermediate change to long term outcomes • Linkage of biological (biomarker, genetics – Perlis et al, STAR*D, Arch Gen Psychiatry June 2007) and clinical data; potential for targeted interventions • Identification of subgroups (differential response -“personalized treatment”) Personalized Treatment Optimizing the Benefit:Risk Ratio Practical Clinical Trials: NIMH Approach • 1999 – 2006: Multiple large clinical trials launched under contract mechanism • 2006 – onward: With completion of practical trials, infrastructure for disorder-focused clinical trials networks formed from nucleus of high-performing sites + coordinating center Clinical Trial Design Patients Phase N Settings Masked Treatment Masked Raters Outcome Measures Efficacy Effectiveness Narrow dx; few comorbidities or concurrent meds II, III Few exclusion criteria 10s – 100s Health care 100s – 1,000s Various Yes (Protocol) No (Clinician / Algorithm) Yes Yes Symptomatic only III, IV Functional, Cost/ Utilization as well Methodology Designed for High Generalizability in Practical Trials • Equipoise design, in some cases using patient preference, reflects practice, increasing generalizability of findings • Real-world patients enrolled (comorbidities OK) • Use of cutting-edge technology, e.g. Web-based quality control of treatment, ratings entry via IVR • Advances in valid and reliable clinical ratings, e.g. QIDSC or QIDS-SR instead of traditional Hamilton score; “allcause discontinuation” as a measure of effectiveness • Outcomes beyond symptomatic ratings, e.g. quality of life, functional measures NIMH Contracts: Practical Clinical Trials • STEP-BD (Bipolar Disorder) – 4,360 / 13 sites – Standard care and random pathways • CATIE (Schizophrenia / Alzheimer’s Disease) – 1,914 / 57 sites – 1,493 in Schizophrenia; 421 in Alzheimer’s Disease – Randomized comparison • STAR*D (Refractory Depression) – 4,041 / 41 sites – Sequential pathways Less than 1/3 of symptomatic bipolar patients reach recovery and remain well over 2 years in STEP-BD • Achieved recovery 58.5% – (< 2 mood symptoms for at least 8 weeks) • Relapse into depression 34.7% • Relapse into mood elevation 13.8% • Total relapse rate 48.5% • Total that stayed recovered over 2 years (100%-48.5%) 51.5% • Total who recovered and remained free of depressive and mood elevation recurrences over 2 years (51.5% out of 58.5% who achieved remission) 30.1% N=1469 who entered symptomatic Perlis et al, STEP-BD, Am J Psychiatry 2006 Feb;163:217-24. Anxiety comorbid conditions with higher risk of relapse in bipolar disorder in STEP-BD without anxiety with anxiety N=489 Overall relapse rate = 41.4% Overall Hazard Ratio (HR)= 1.764 ( 2=10.9, P=0.001) HR=1.55 for one disorder HR=2.17 for two or more disorders HR=2.07 for social anxiety disorder HR=2.45 for PTSD Otto et al., STEP-BD, Br J Psychiatry 2006 Jul;189:20-5. April 26, 2007 Effectiveness of Adjunctive Antidepressant Treatment for Bipolar Depression Gary S. Sachs, M.D., Andrew A. Nierenberg, M.D., Joseph R. Calabrese, M.D., Lauren B. Marangell, M.D., Stephen R. Wisniewski, Ph.D., Laszlo Gyulai, M.D., Edward S. Friedman, M.D., Charles L. Bowden, M.D., Mark D. Fossey, M.D., Michael J. Ostacher, M.D., M.P.H., Terence A. Ketter, M.D., Jayendra Patel, M.D., Peter Hauser, M.D., Daniel Rapport, M.D., James M. Martinez, M.D., Michael H. Allen, M.D., David J. Miklowitz, Ph.D., Michael W. Otto, Ph.D., Ellen B. Dennehy, Ph.D., and Michael E. Thase, M.D. Intensive psychosocial interventions for bipolar depression better than collaborative care, but over a third never reach recovery 80 Intensive Treatment Collaborative Care 70 60 50 % Well 40 30 20 10 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Month 8 9 10 11 1-year recovery rate for intensive group, 105/163 [64.4%]; for CC, 67/130 [51.5%]; log-rank 2(1) = 6.20, p = 0.013; hazard ratio (HR) = 1.47; 95% CI = 1.08-2.00 Miklowitz et al., STEP-BD, Arch Gen Psychiatry, April 2007 12 Am J Psychiatry 164:201-204, February 2007 © 2007 American Psychiatric Association Special Article STAR*D: What Have We Learned? A. John Rush, M.D. STAR*D represents a 7-year effort by literally hundreds of people and thousands of patients. Future reports will 1) compare longer-term outcomes of the various randomized treatments (e.g., does cognitive therapy prevent relapse better than medication as either a switch or augmentation strategy?); 2) identify which patients benefit from which treatments (e.g., do different patients [defined by different clinical features or genetic polymorphisms] respond differently to different treatments?); and 3) determine whether different treatment sequences (in steps 1 to 4) are preferred for some but not other patients. Volume 353:1209-1223 September 22, 2005 Number 12 Effectiveness of Antipsychotic Drugs in Patients with Chronic Schizophrenia Jeffrey A. Lieberman, M.D., T. Scott Stroup, M.D., M.P.H., et al. for the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) Investigators CATIE: Primary Questions Addressed • How do the atypical antipsychotic medications compare with an older, less expensive conventional antipsychotic? • How do the atypical antipsychotics compare to one another? • Are the atypical antipsychotics cost-effective? Stroup TS et al. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29:15-31. Use of Atypical Antipsychotic Medications in U.S. TRx (000s) 50,000 40,000 30,000 20,000 10,000 0 1993 1994 1995 Conventionals 1996 Clozaril 1997 1998 Risperdal 1999 2000 Zyprexa 2001 2002 Seroquel 2003 Geodon 2004 2005 Abilify Source: IMS NPA Plus, Dec 05. Lieberman – Presentation to NIMH Advisory Council, Sept 2006 CATIE Schizophrenia Trial Design Phase 1* Double-blind, random treatment assignment. Phase 3 Phase 2 Participants who discontinue Phase 1 choose either the clozapine or the ziprasidone randomization pathways CLOZAPINE OLANZAPINE (open-label) 1500 participants with schizophrenia QUETIAPINE R R •ARIPIPRAZOLE •CLOZAPINE •FLUPHENAZINE DECANOATE •OLANZAPINE •PERPHENAZINE RISPERIDONE ZIPRASIDONE R ZIPRASIDONE OLANZAPINE, QUETIAPINE or RISPERIDONE Participants who discontinue Phase 2 choose one of the following open-label treatments •QUETIAPINE OLANZAPINE, QUETIAPINE or RISPERIDONE •RISPERIDONE •ZIPRASIDONE PERPHENAZINE No one assigned to same drug as in Phase 1 •2 of the antipsychotics above Responders stay on assigned medication for duration of 18-month treatment period * Phase 1A: participants with tardive dyskinesia do not get randomized to perphenazine Phase 1B: participants who fail perphenazine will be randomized to an atypical (olanzapine, quetiapine, or risperidone) before they are eligible for Phase 2 Stroup et al 2003 Proportion of Patients without Event PHASE 1: Time to Discontinuation for Any Reason 1 0.8 0.6 0.4 36% 26% 25% 21 % 18% 0.2 0 0 3 15 12 9 6 Time to Discontinuation for Any Cause (mo) Olanzapine (n=330) ▬▬▬ Olanzapine (n=330) Perphenazine (n=257) Quetiapine (n=329) ▬▬▬ Risperidone (n=333) Risperidone (n=333) ▬▬▬ Ziprasidone (n=183) ▬▬▬ Quetiapine (n=329) 18 Ziprasidone (n=183) ▬▬▬ Perphenazine (n=257) Problems with Movement During the Trial Percent (%) 15% 10% 5% 0% Perphenazine Risperidone Quetiapine Olanzapine Ziprasidone Exposure-adjusted Mean (ng/mL) Prolactin: Change from Baseline 20.0 15.0 10.0 5.0 0.0 -5.0 -10.0 -15.0 Perphenazine Risperidone Quetiapine Olanzapine Ziprasidone Body Weight: Change from Baseline Weight Gain >7% 40% 30% 20% 10% Exposure-adjusted Mean (mg/dL) Exposure-adjusted Mean (mg/dL) 0% Perphenazine Risperidone Quetiapine Olanzapine Ziprasidone Fasting Glucose: Change from Baseline 15.0 10.0 5.0 0.0 Perphenazine Risperidone Quetiapine Olanzapine Ziprasidone Fasting Triglycerides: Change from Baseline 40.0 25.0 10.0 -5.0 -20.0 Perphenazine Risperidone Quetiapine Olanzapine Ziprasidone American Journal of Psychiatry 163:600-610, April 2006 Effectiveness of Clozapine Versus Olanzapine, Quetiapine, and Risperidone in Patients With Chronic Schizophrenia Who Did Not Respond to Prior Atypical Antipsychotic Treatment Joseph P. McEvoy, M.D., Jeffrey A. Lieberman, M.D., T. Scott Stroup, M.D., M.P.H., Sonia M. Davis, Dr.P.H., Herbert Y. Meltzer, M.D., Robert A. Rosenheck, M.D., Marvin S. Swartz, M.D., Diana O. Perkins, M.D., M.P.H., Richard S.E. Keefe, Ph.D., Clarence E. Davis, Ph.D., Joanne Severe, M.S., John K. Hsiao, M.D. for the CATIE Investigators CATIE Phase 2: Preference Pathways (for people who discontinue Phase 1) Clozapine—open-label Efficacy Pathway Randomized Olanzapine, Quetiapine, or Risperidone—drug not taken in Phase 1 Tolerability Pathway Randomized Ziprasidone Stroup TS et al. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29:15-31. Proportion of Patients without Event PHASE 2E: Time to Discontinuation for Any Reason 1 0.8 0.6 0.4 44% 29% 14% 7% 0.2 0 0 3 6 9 12 15 Time to Discontinuation for Any Cause (mo) Clozapine (N=45) Olanzapine (N=17) 18 Quetiapine (N=14) Risperidone (N=14) Proportion of Patients without Event PHASE 2T: Time to Discontinuation for Any Reason 1 0.8 0.6 0.4 36% 33% 23% 16% 0.2 0 0 4 8 12 Time to Discontinuation for Any Cause (mo) Olanzapine Quetiapine 16 Risperidone Ziprasidone Negative Symptoms and Cognitive Function • No differences between atypical antipsychotics and a conventional antipsychotic (perphenazine) on negative symptoms and cognitive functions December 1, 2006 Older Medication May Be More Cost-Effective for Some Patients with Schizophrenia A new study analyzing the economic implications of CATIE concludes that the older (first generation) antipsychotic medication perphenazine was less expensive and no less effective than the newer (second generation) medications used in the trial during initial treatment, suggesting that older antipsychotics still have a role in treating schizophrenia. Total monthly health costs, a figure that includes both average medication costs and inpatient and outpatient costs, were up to 30 percent lower for those taking perphenazine than for those taking the second generation medications. -- NIMH Press Release Re: Rosenheck et al, Am J Psychiatry, December 2006 Study May Boost Use of Cheaper Antipsychotic Drug By Avery Johnson, The Wall Street Journal, December 1, 2006 For the cost-effectiveness portion of the Catie study, a team of researchers led by Yale Medical School's Robert Rosenheck found that patients taking the generic antipsychotic paid $960 in average health costs per month, including the $50 price of the drug. The average monthly cost of treatment with Eli Lilly & Co.'s Zyprexa, for instance, was $1,404 -- the lowest of the branded drugs -- after accounting for the $545 per month cost of the antipsychotic, plus additional medications and hospital costs. Average health costs for patients on Johnson & Johnson's Risperdal were $1,533 a month, including $474 for the drug. Two other branded drugs were also analyzed CATIE HIGHLIGHTS – All antipsychotic medications studied are effective but have substantial limitations reflected by high discontinuation rates – Olanzapine and Clozapine show the best efficacy but the worst side effects – Perphenazine was surprisingly comparable to atypicals – Differences in types and severity of side effects – Ziprasidone has least weight and metabolic side effects (Aripiprazole was released later) “CATIE has opened the door to more choice in treatment options." -- Robert Rosenheck, M.D. Treatments for persons with schizophrenia must be individualized. Doctors and patients must carefully evaluate the tradeoffs between efficacy and side effects and past treatment history in choosing an appropriate medication. Lieberman – Presentation to NIMH Advisory Council, Sept 2006 Issues in Schizophrenia Treatment Research Still Needing Attention • Need for strategies beyond clozapine or alternatives to clozapine for patients with refractory symptoms • Rational antipsychotic polypharmacy? • What are optimal strategies for first-episode psychosis? • How to enhance treatment adherence ? Lieberman – Presentation to NIMH Advisory Council, Sept 2006 355:1525-1538 October 12, 2006 Number 15 Effectiveness of Atypical Antipsychotic Drugs in Patients with Alzheimer's Disease Lon S. Schneider, M.D., Pierre N. Tariot, M.D., Karen S. Dagerman, M.S., Sonia M. Davis, Dr.P.H., John K. Hsiao, M.D., M. Saleem Ismail, M.D., Barry D. Lebowitz, Ph.D., Constantine G. Lyketsos, M.D., M.H.S., J. Michael Ryan, M.D., T. Scott Stroup, M.D., David L. Sultzer, M.D., Daniel Weintraub, M.D., Jeffrey A. Lieberman, M.D., for the CATIE-AD Study Group "The antipsychotic medications may be effective against some symptoms in Alzheimer's patients compared to placebo, but their tendency to cause intolerable adverse side effects in this vulnerable population offsets their benefits." Lon Schneider, MD Schneider et al, CATIE-AD, N Engl J Med, Oct 2006 Psychotherapy in NIMH Effectiveness Trials – completed • STEP-BD (Bipolar Depression) – 3 types of structured psychotherapy are effective adjuncts to pharmacotherapy (Miklowitz et al, Arch Gen Psychiatry, April 2007) • STAR*D (Refractory Depression) – Only 26% of patients agreed to treatment with cognitive therapy (CT) as a second-line treatment after inadequate response to citalopram. Responses to CT, as monotherapy or augmenting citalopram, were equivalent to medication-only groups. Time to remission was slower with CT but with fewer side effects (Thase et al, & Wisniewski et al, Am J Psychiatry, May 2007) Psychotherapy in NIMH Effectiveness Trials – in progress • Research Evaluating the Value of Augmenting Medication with Psychotherapy (REVAMP / Chronic Major Depression) – Does CBASP or supportive psychotherapy add to pharmacotherapy in the treatment of chronic forms of major depression? (Kocsis et al) • Coordinated Anxiety Learning and Management (CALM / Anxiety Disorders) – Does computer-based individualized CBT add to pharmacotherapy for anxiety disorders in primary care? (Roy-Byrne et al) What Questions Should Be Pursued Next? • Widely used treatments and treatment combinations that are untested? • New molecules ready for wider testing? • Patient attrition? • Longer-term outcomes? • Tailoring treatment to individuals? • Enhancing cost efficiency? • Practice procedures that are controlled by payor costs without regard to patient outcomes? Rush – Presentation to NIMH Advisory Council, Sept 2006 What’s Next at NIMH • Three new clinical trials networks (Depression, Bipolar Disorder, Schizophrenia), building upon completed Practical Clinical Trials • Platform funding • Central data management • Collaboration with new partners • Identify challenging public mental health questions suitable for study on Networks • Continue regular grant support of non-Network services and interventions research www.nimh.nih.gov/ncdeu/index.cfm For complete details of NIMH-supported Clinical Trials, please see http://www.nimh.nih.gov/studies/index.cfm