Document 11615568

advertisement

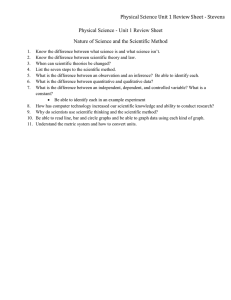

Author Anton J. Kuzel, MD, MHPE Professor of Family Medicine Mixed methods in health services research: Doing what comes naturally to clinicians Virginia Commonwealth University Presenter Steven H. Woolf, MD, MPH Professor of Family Medicine, Preventive Medicine and Community Health Virginia Commonwealth University Executive Vice President for Policy Development, Partnership for Prevention AcademyHealth Meeting June 8, 2004 San Diego, California Two classic ways of knowing in clinical medicine Goals of this talk Briefly describe how clinicians appear to effortlessly use at least two basic “ways of knowing” knowing” in caring for their patients Summarize typical reasons for using “mixed methods” methods” in health services research, and suggest analogies in the clinical enterprise Illustrate a simple application of “mixed methods” methods” in a recent study of medical errors in primary health care Two classic ways of knowing in clinical medicine “Subjectifying” Subjectifying” Patient as maker of meaning for action that is dependent upon patient’ patient’s conscious behavior Appropriate “Objectifying” Objectifying” Patient as “body machine” machine” for action that is not dependent upon patient’ patient’s conscious behavior Appropriate “Body machine” machine” model has validity Similar anatomy and physiology among humans is foundational for much of Western medicine Western medicine can reduce suffering and prolong life, hence “body machine” machine” appears ethical Skillful clinicians know that there is more to it than this 1 “Maker of meaning” model Most clearly needed when task is behavior change (e.g., taking medicines, stopping smoking) “Transtheoretical” Transtheoretical” model of behavior change requires particularized understanding of the meaning of current and imagined future behavior Integration of the two models Analogies with “mixed methods” research At least five typical reasons for using “mixed methods” methods” in health services research Each has an analogy in clinical medicine, in which the objective and subjective models are integrated 1. Instrument creation 2. Triangulation Research: Looking at something using more than one way of knowing, or more than one viewpoint Clinical analogy: Hypertension as a result of disordered regulatory mechanisms (clinician view); hypertension as a result of too much stress (patient view) Explanatory models of signs or symptoms Hypertension as a disorder of vascular and fluid regulatory mechanisms (body machine model) Hypertension as a literal translation (too much tension – maker of meaning model) Skillful clinician respects patient model and works to “coco-create” create” the meaning of the hypertension Research: Making quantitative tools using qualitative methods Clinical analogy: Clinical inventories (e.g., depression screening instruments) were initially developed by observations and interviews 3. Data transformation Research: Initial qualitative analysis of data to develop codes, then using descriptive statistics to describe how often they are observed Clinical analogy: Astute clinicians recognize patterns in their everyday experience, and apply quantitative data to help characterize patterns, suggest path of investigation Illustration from our work 2 Harms Reported by Patients 4. Explanatory model Economic 7% Anger and related emotions 34% Personal worth 11% Physical 23% Relationship effects 10% Psychological 70% Research: Qualitative data and analysis are used to explain quantitative data (e.g., patterns in the data, or the meaning of outliers) Clinical analogy: Blood pressure logs show elevations on Mondays – eventually found to be result of weekend binge drinking Anxiety about health 6% Opportunity costs 7% Other emotions 2% Source: Kuzel et al. 5. “Nested” design Research: Both quantitative and qualitative questions are asked and answered in the same study using appropriate methods Clinical analogy: What is the efficacy of a new blood pressure medication, and what is the patient’ patient’s experience of taking the new medicine? Coming full circle A pragmatist will employ values, beliefs, and methods that seem likely to result in desired consequences. Adhering to a narrow set of options reduces the possibilities for positive action. As Borkan suggests, we should embrace numbers and narratives (Ann Fam Med 2004;2:42004;2:4-6) References for typology of mixed methods models in primary care research Cresswell JW, Fetters MD, Ivankova NV. Designing a mixed methods study in primary care. Ann Fam Med 2004;2:72004;2:7-12 Stange KC, Zyzanski SJ. Integrating qualitative and quantitative research methods. Fam Med 1989;21:4481989;21:448-451. 3