Markets Matter: Expect a Bumpy Ride Emissions

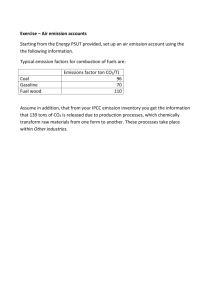

advertisement