Public Reporting of Long-Term Care Quality R. Tamara Konetzka, PhD University of Chicago

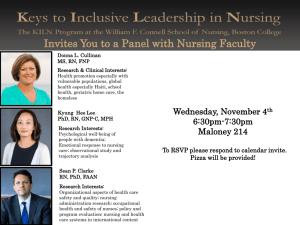

advertisement

Public Reporting of Long-Term Care Quality R. Tamara Konetzka, PhD University of Chicago June 2009 Motivation for Public Reporting Simple economic theory of markets assumes: – Perfect information – Perfect competition – Consumers choose price/quality combination Absence of typical market attributes in health care: – Information Asymmetries Difficult for consumers to judge quality Little incentive for providers to compete on quality Goals of Public Reporting Public reporting of quality is intended to improve quality by: – Giving consumers information needed to shop on quality – Giving providers incentive to compete on quality If either or both occurs, quality should increase Potential Unintended Consequences “Cream-skimming” or selection of patients based on risk “Teaching to the test” or decreased attention to unreported aspects of quality Increased disparities in quality – Some consumers less able to access and use quality information – Some providers less able to invest in quality improvement to improve scores Additional Challenges for LTC Markets historically have not been very competitive; nursing home beds not always available Pervasive cognitive impairment Choice of provider tied strongly to residence and proximity to family Segregation and disparities are entrenched Most providers depend on public payers, especially Medicaid Quality of life is crucial yet difficult to measure Nursing Home Compare Launched November 12, 2002 Publicly release quality information: http://www.medicare.gov/NHCompare All Medicare- and Medicaid-certified NHs – 16,000 nursing homes 10 quality measures – 4 post-acute care – 6 chronic care Staffing, inspections, ownership, size Subsequent Adjustments 9 quality measures added over time 5-star rating system – Added in December 2008 – Star ratings on: health inspections staffing clinical quality measures all three combined – Intended to be an accessible summary of data Home Health Compare Launched fall 2003 Publicly release quality information: http://www.medicare.gov/HHCompare All Medicare-certified Home Health Agencies – 9,000 agencies 11 quality measures initially (now 12) Empirical Evidence: Intended Effects Early studies of trends post-NHC: positive for some/most clinical measures, modest in magnitude (Zinn et al. 2005; Castle et al. 2007) Pre-post trends in a subset of nursing homes: 2/5 clinical measures showed significant but modest improvement (Mukamel et al. 2008) Most providers reported looking at and taking some action in response to public reporting (Mukamel et al. 2007) With additional identification Using small facilities as a control group: 2/3 post-acute care measures show modest but significant improvement (Werner et al. 2009) Nursing homes in more competitive markets showed significant and positive improvement in clinical measures (Grabowski 2008; Castle et al. 2008) Magnitudes range from 1-10% decrease in adverse outcomes Empirical Evidence: Teaching to the test Little spillover to unreported care found in post-acute setting on average Nursing homes that do very well on reported care see larger spillovers to unreported care Nursing homes that do not do well on reported care may worsen quality of unreported care (Werner Konetzka Kruse 2009) Adjusted changes in unreported quality Empirical Evidence: Inadequate risk-adjustment and cream-skimming More extensive risk adjustment would change the quality rankings of nursing homes (Mukamel et al., 2008) – but not of home health agencies (Murtaugh et al., 2007) Some evidence of limited cream-skimming as indicated by changes in admissions characteristics (Mukamel et al., 2009) Changes in admissions characteristics are also consistent with improved sorting (Werner et al., 2009) Empirical Evidence: Disparities Percent of Residents Without Moderate/Severe Pain (adjusted) 0.77 0.765 0.76 0.755 black 0.75 hispanic w hite 0.745 0.74 0.735 0.73 Pre-NHC Post-NHC Empirical Evidence: Consumer Use In a survey of 4,754 family members of nursing home residents (Castle, 2009): – 31% reported using the Internet to choose a facility – 12% recalled using Nursing Home Compare – Most seemed to understand the information Evidence is still emerging on whether improvement is due more to consumer or provider response Conclusions Public reporting can play a positive but modest role in improving reported aspects of quality We should not expect substantial spillovers to unreported aspects of quality Evidence is still incomplete/emerging Unanswered Questions Consumer use of report cards Production functions of quality improvement in response to report cards Unintended consequences/ disparities Sorting and price effects Longer-run and dynamic effects Improved risk-adjustment Non-nursing-home settings Effects on quality of life