Patterns of Coordination Within and Between Stages of Work:

advertisement

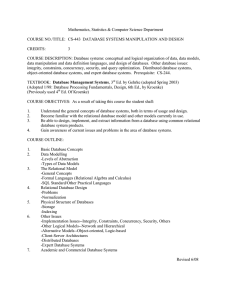

Patterns of Coordination Within and Between Stages of Work: Evidence of Modularity in Healthcare Jody Hoffer Gittell The Heller School for Social Policy and Management Brandeis University Waltham, MA 02454 (781) 736-3680 jgittell@brandeis.edu Cori Kautz The Heller School for Social Policy and Management Brandeis University Waltham, MA 02454 (781) 736-3736 ckautz@brandeis.edu R. William Lusenhop The Heller School for Social Policy and Management Brandeis University Waltham, MA 02454 (781) 736-2582 lusenhop@brandeis.edu Dana Beth Weinberg Queens College Queens, NY (718) 997-2915 dana_weinberg@qc.edu DRAFT – Do not quote or cite without permission from the author. Special thanks Dr. John Wright of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and his colleagues for partnering with us on data collection for this project and to Elizabeth Lingard for advising us on outcomes measurement for this patient population. Thanks also to Carliss Baldwin, Steve Eppinger and participants in the 7th International DSM Conference for feedback on extending the theory of modularity to healthcare delivery. We thank patients and providers from Brigham and Women’s Department of Orthopedics, and its downstream partners, for participating in this study. We thank Ann-Marie Audet, Steve Schoenbaum and Mary Jane Koren of the Commonwealth Fund of New York for their support of this study. Patterns of Coordination Within and Between Stages of Work: Evidence of Modularity in Healthcare We explore the proposition that healthcare delivery systems are modular in much the same way that many manufacturing industries have become. We followed surgical patients from acute care to rehab care and to home care, surveying their providers at each stage about the coordination of their care. Using the design structure matrix methodology, we found a modular pattern of coordination with relatively strong ties within stages of care and relatively weak ties between stages of care. Consistent with the theory of modularity, system integrators help to integrate across stages of care, though informal caregivers unexpectedly play the most prominent role. We find that patterns of coordination are more modular for more complex patients, consistent with modularity theory, but that these patients also have marginally poorer outcomes. We conclude with implications for modularity theory, coordination theory, and for making modularity work in healthcare. (145 words) 2 How do people work together and what are the patterns through which they interact? Early research on patterns of work group interaction was undertaken in the MIT Group Networks Laboratory in the 1950s (e.g., Bavelas, 1950; Leavitt, 1951; Shaw and Rothschild, 1956), abandoned for several decades (Monge and Contractor, 2001), then revived in recent years (Argote, Turner and Fichman, 1989; Brown and Miller, 2000; Sparrowe, 2001; Cummings and Cross, 2003; Perlow, Gittell and Katz, 2004). Distinct from the large body of research on work groups, this much smaller body of research focuses on measuring specific ties between people who work together rather than measuring more aggregate concepts such as group cohesion. The focus on ties has begun to result in a more fine-tuned understanding of the patterns of interaction through which work gets done, whether those interactions involve helping, knowledge sharing or coordination. This approach has enabled researchers to better identify organizational practices and broader institutional forces that shape those patterns in ways that are conducive to getting work done. While this research sheds light on the existence and usefulness of ties between members of work groups, it can also help us to answer the question – where should ties be relatively strong and where can they be relatively weak? If it is not feasible or efficient to build strong ties with every person in one’s work group, the question of how to best focus one’s limited time and attention on developing strong ties where they really matter becomes relevant. This question is critical from both an organizational efficiency perspective as well as from a personal perspective of how to best focus one’s time and effort. The answer to this question can inform decisions regarding the design of coordinating mechanisms as well as the design of jobs. Coordination theory uses the concept of task interdependency to answer the question of where strong ties are needed and where weak ties will suffice. Coordination, most simply stated, is the management of task interdependencies (Malone and Crowston, 1994). In Thompson’s (1967) seminal work on coordination, he argued that different types of task interdependencies call for different types of coordination. To summarize his argument using the concept of bandwidth introduced by Daft and Lengel (1986), weaker (sequential or pooled) task interdependencies require relatively low bandwidth forms of 3 coordination, while stronger (reciprocal or iterative) task interdependencies require relatively high bandwidth forms of coordination. According to the theory of relational coordination, communication and relationship ties are a key source of bandwidth for coordinating work (Gittell, 2005). By extension then, coordination theory suggests that weak task interdependencies can be coordinated through weak ties, while strong task interdependencies require strong ties for their successful coordination. The theory of modularity builds on coordination theory by predicting that certain patterns of weak and strong ties are likely to emerge for coordinating complex work processes when the underlying patterns of task interdependence become modularized. Furthermore, boundaries between firms are likely to be formed between modules or “clumps of task interdependence.” After exploring the theory of modularity and considering the arguments put forth by its critics, we will analyze data from a study of patient care coordination to assess the degree to which the patterns of coordination observed in healthcare conform to the expectations of modularity theory, and the degree to which these coordination patterns adapt to meet the needs of more complex patients. We then conclude with implications for modularity theory, for coordination theory, and for making modularity work in healthcare. Modularity Economic historian Richard Langlois (2002) argues that production has become increasingly modularized over time, driven both by efficiency benefits and by the greater potential for innovation. Modules are determined by the relative strength of task interdependencies in a work process, with the strongest task interdependencies found within the modules and the weakest task interdependencies found between the modules (von Hippel, 1990). Modularity allows participants in a work process to focus on building strong ties with others who work at the same stage of the process and whose work is most highly interdependent with their own, while allowing them to maintain relatively weak ties with those who work at different stages of the process, whose work is less highly interdependent with their own (Baldwin and Clark, 2000; 2004). Furthermore, modules enable innovation because they enable rapid reconfiguration and recombination of elements of a process, therefore increasing the options available for changing any given work process and even customizing it to the needs of a particular customer (ibid). Although there is 4 relatively little need for coordination to occur directly between modules, due to their relative independence, a crucial coordinating role is expected for participants who play systems integrator roles (Sosa, et al, 2003). The theory of modularity specifies three factors that facilitate or inhibit modularization. The first factor, mentioned above, is the underlying pattern of task interdependencies in the work process. A work process can be highly integrative with task interdependencies that do not cluster into modules, such that it is not amenable to modularization. Alternatively, task interdependencies may evolve in such a way, or be designed in such a way, that they cluster into relatively bundles of tasks (von Hippel, 1990). In a fully modular work process, task interdependencies are reciprocal within modules, requiring high bandwidth forms of coordination, and sequential or pooled between modules, requiring low bandwidth forms of coordination. The second factor is the existence of protocols or rules for coordinating the interface between modules of the work process. Even when task interdependencies cluster into distinct modules, modularization can be inhibited by the absence of relatively well-defined protocols or rules governing the handoffs between the modules. According to coordination theory, protocols, routines and standard operating procedures are relatively low-bandwidth coordinating mechanisms that facilitate the interface between tasks when task interdependence is relatively weak (Daft and Lengel, 1986; Argote, 1982; Gittell, 2002). Moreover, researchers have found that boundary objects can be designed to facilitate the interface between tasks by providing a clear representation of the work in process (Arias and Fischer, 2000). Along the same lines, Baldwin and Clark (2000) argue that measurability of the output of each module is critical for modularization because measurability enables contracts to be written that specify the interfaces between modules. The third factor that enables modularization is the existence of system integrators whose job is to ensure that modules adhere to the protocols or rules that govern the process, and to weave together the discrete modules into a coherent process (Sosa, et al, 2003). System integrators play the role of boundary spanners or liaisons, people whose primary task according to coordination theory is to integrate the work 5 of other people (Galbraith, 1995; Lievens, 2000). In a modular system, system integrators are responsible for the enforcement and the adjustment of protocols, as well as the potential customization of protocols to meet an unanticipated need. As we will argue below, each of these three factors has come to characterize the healthcare delivery system. But first, let us consider alternative perspectives regarding the desirability of modularity. Critique of Modularity In direct contrast to Langlois’ argument regarding the benefits of modularization, Sabel and Zeitlin (2004) argue that modularization undermines the ability of organizations to innovate and learn. The new economy establishes strict limits to modularization, they argue, due to the “impossibility of establishing standard design interfaces so comprehensive and stable that customers and suppliers can in effect interact as if operating in spot markets for complex components or subassemblies without jeopardizing their long-term survival” (ibid). The growing practice of co-design requires collaborators to routinely “question and clarify their assumptions about their joint project” using methods such as benchmarking, co-location of personnel, problem-solving teams and quality standards that enable the parties to reconsider the partitioning of tasks across boundaries in a way that modularization does not allow (ibid). Following these authors and others who have explored the dynamics of inter-firm coordination and learning (Powell, 1990; Grandori and Soda, 1995; Helper, MacDuffie and Sabel, 2003), we might expect modularity to be less effective, the greater the complexity of the process. With a more complex process, the boundaries between clusters of tasks arguably need to become more permeable to enable feedback and learning to occur. This expectation is consistent with coordination theory, which argues that complexity of various kinds increases the usefulness of high bandwidth forms of coordination (Argote, 1982; Daft and Lengel, 1986) and relational forms of coordination in particular (Gittell, 2002). We would therefore expect based on these arguments to find coordination patterns that are less modular, and more integrative, when the work process is more complex. 6 The theory of modularity as posed by Baldwin and Clark (2000) and Eppinger and colleagues (1994) argues, to the contrary, that modularity is an effective response to complexity. Modular systems enable participants to focus on building strong ties within modules, where task interdependencies are greatest, and to rely on weak ties between modules, where task interdependencies are weakest. Modularity, according to this theory, is more necessary and more powerful, the more complex the process. The Case of Patient Care Looking to the characteristics of modularization described above, there is considerable evidence that for better or worse, the healthcare delivery system is growing increasingly modularized. Distinct stages of care – emergency care, intensive care, acute care, rehab care, home care and primary care – have been formally defined based on acuity levels of the patient. The definition, formalization, and enforcement of these levels of care have occurred through negotiations over time between clinicians who deliver the care and payers, both governmental and private, who pay for it. Patients are expected to move from one level of care to the next when they meet externally defined criteria for transfer; and if they are not moved in a timely way, the payer can refuse to pay for the higher level of care because the patients does not meet the criteria for receiving it. The stages of care are designed around the acuity levels of the patient, but also are intended to take place at a point where the patient is considered sufficiently stable for transfer. There is an expected clustering of task interdependencies by stage of care, with iterative, reciprocal interdependencies within a given stage of care, and more clearly defined, sequential interdependencies between stages of care, as illustrated above in Figure 1. Secondly, in addition to well-defined stages of care, there are increasingly well-defined protocols for the hand-off of patients from one stage of care to the next. Standardized protocols have evolved for the transfer of information about patients, typically a three-page discharge form summarizing basic patient information, and including evaluations of patient status from care providers who worked with the patient at previous stages of care, and their recommendations for further treatment. For many diseases and conditions, clinical pathways have been developed or are currently under development, providing a 7 process map for governing the interfaces between stages of care (e.g. Wheelwright, 1992; Bohmer, 1998; Gittell and Weiss, 2004). Third and finally, system integrators of various kinds can be found in the healthcare delivery system, though there are sometimes competing roles and a lack of clarity regarding who is or should be playing this role. Managed care organizations employ case managers who oversee handoffs across stages, primarily with the goal of ensuring that patients do not remain at a more costly stage of care longer than their condition would justify. Each stage of care has its own case managers who are expected to manage the handoff of the patient from the previous stage and to the subsequent stage of care. In addition, the primary care physician has been placed in the role of system integrator in some healthcare delivery systems, with the expectation that he or she will coordinate handoffs between stages of care (Stille, Jerant, Bell, Meltzer and Elmore, 2005). Yet another potential system integrator is the informal caregiver – the family member or friend of the patient. Recent research has documented the growing role of the informal caregiver in today’s healthcare system (Kirk and Glendinning, 1998; Lyons and Zarit, 1999; Donelan, Hill, et al. 2002). In addition to providing care when the patient returns home, informal caregivers play a valuable role in coordinating the transfer of the patient between stages of care (Lusenhop, Weinberg, Gittell and Kautz, 2005). The presence of these three factors suggests that the healthcare system is becoming modularized by stage of care. Based on these factors, we expect to find modular patterns of coordination between healthcare providers who are working with a given patient, with relatively strong coordination ties within modules, and relatively weak coordination ties between modules. Hypothesis 1: The patient care process is expected to be modular by stage of care, with relatively strong coordination ties within stages and relatively weak coordination ties between stages. Consistent with modularity theory, a subset of providers in the healthcare system is expected to play a system integrator role. In particular, we expect that primary care physicians, case managers who 8 work for managed care organizations, and the patient’s informal caregiver, will play the role of system integrators, displaying relatively strong patterns of coordination with providers at each stage of care. Hypothesis 2: Strong coordination ties are expected between system integrators (case managers employed by managed care organizations, primary care physicians, and informal caregivers) and providers at each stage of care. Together, these strong ties within stages, weak ties between stages, and strong ties between system integrators and each of the stages, characterize the patterns of coordination expected by the theory of modularity. How might these modular patterns of coordination be expected to vary, depending on the complexity of the patient? Based on the argument that modularity is a response to complexity (Baldwin and Clark, 2000), we would expect that the modularity of coordination patterns will be even more pronounced for more complex patients than for less complex patients. Hypothesis 3a: For more complex patients, coordination ties within stages and with system integrators are stronger than those for less complex patients, while ties between stages are the same or weaker. According to the arguments above regarding the limitations of modularity (Sabel and Zeitlin, 2004), and the need for higher bandwidth forms of coordination when complexity is high (Daft and Lengel, 1986), we would expect more complex patients to be less amenable to modular forms of coordination. The alternative to Hypothesis 3a, therefore, is: Hypothesis 3b: For more complex patients, patterns of modularity are less pronounced, with coordination ties between stages that are stronger than those for less complex patients. METHODS In this study, we explore modularity in the coordination of care for knee arthroplasty patients who received surgery at one particular focal hospital, a large well-regarded urban teaching hospital, who then went on to receive rehab and home care from a variety of provider organizations. We surveyed patients 9 about the quality of their care and the quality of their clinical outcomes, and surveyed providers about their coordination with other providers involved in caring for the same patient. For analyzing patterns of coordination and assessing the degree of modularity in those patterns, we used a matrix form of analysis originally developed by Shepard (1981) and further developed by Eppinger and his colleagues (Eppinger, et al, 1994; Sosa, et al, 2003). This form of analysis, known as Dependency Structure Matrix (DSM), has been applied in recent years primarily to the design of products. The current paper is relatively unique in applying the DSM methodology to a service delivery process. In addition, Sosa, et al (2003) argue that the ideal use of the DSM methodology is to first model the dependencies between tasks, then model the patterns of coordination, and assess the extent to which the two “fit.” However, given that the task dependencies for patient care are relatively well known – reciprocal within stages of care, and sequential between stages of care – we have skipped that step and instead focus our efforts on modeling the patterns of coordination. All data, measures and analytical techniques are further described below. Data Collected for this Study Patients were eligible for inclusion in this study if they were admitted to the focal hospital for primary, unilateral total knee arthroplasty with a diagnosis of osteoarthritis between November 2003 and May 2004. All eligible patients were sent an initial survey prior to their surgery, asking them to participate and to answer questions regarding their pre-operative status. We received 222 responses to 357 surveys that were sent to eligible patients, for an enrollment rate of 62 percent. Hospital administrative records were obtained for each patient who enrolled in this study, to extract additional data not captured through the surveys. We surveyed a sample of the patient’s care providers at six weeks after discharge. For each patient, we identified and surveyed a subset of the different types of care providers responsible for the patient at the acute, rehab, and home stages of care. See Table 1 for the types of providers who were surveyed, due to expected ease of access, and for types of providers they were surveyed about. Providers were surveyed about coordination with each other provider who was assigned to the same patient, so we have information about coordination even with those providers who were not surveyed, and about 10 coordination with those who were surveyed but failed to respond. We surveyed a total of 1389 providers who were assigned to the 222 patients enrolled in our study, on average 6 providers per patient. A total of 519 providers responded, for a response rate of 37 percent, or on average, about 2 providers per patient. [Insert Table 1 about here.] We supplemented these provider surveys with 42 structured interviews – 10 with acute care providers, 8 with rehab and home care providers, 12 with informal care givers (friend or family of the patient) and 12 with patients themselves. Relational Coordination The instrument used to test relational coordination was developed and tested in Gittell, et al (2000), based on a survey that was initially used to measure relational coordination among employees in the flight departure process (Gittell, 2005). Each respondent was asked seven questions about his or her coordination with providers who cared for that patient in each of the three stages of care: How frequently did you communicate with each of these people about the status of Patient X?; Did these people communicate with you in a timely way about the status of Patient X?; Did these people communicate with you accurately about the status of Patient X?; When problems occurred regarding the care of Patient X, did these people blame others or work to solve the problem?; To what extent did these people share your goals for the care of Patient X?; How much did these people know about your work with Patient X?; and How much did these people respect your work with Patient X? These questions have been used to assess overall coordination within a particular healthcare setting, and patient-specific coordination in a particular healthcare setting, but have never before been used to assess patient-specific coordination across multiple settings. Responses were measured on a five-point Likert scale. To measure relational coordination within stages, a set of seven scores (frequent, timely, accurate, problem-solving communication, shared goals, shared knowledge, mutual respect) was computed for each respondent based on his or her responses regarding the providers who worked at the same stage of work. The seven scores were combined into a single index, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.83, called relational coordination within stages, measured for each individual respondent. To measure the strength of ties 11 between stages, a similar set of seven scores was computed for each respondent by averaging his or her responses regarding providers in all stages of care other than his or her own. These seven scores were then combined into a single index, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.80, called strength of ties between stages, measured for each individual respondent. Finally, to measure the strength of ties with system integrators, a similar set of seven scores was computed for each respondent by averaging his or her responses regarding each of the system integrators. These seven scores were then combined into a single index, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.85, called relational coordination with system integrators, measured for each individual respondent. Each of these indices easily exceeds the minimum alpha of 0.70 traditionally used as a standard for index validity (Nunnally, 1978). Table 2 shows the descriptive data for our study, including means, standard deviations and a correlation matrix. [Insert Table 2 about here.] Patient Complexity There are multiple patient characteristics that can increase the complexity of care, even for a straightforward procedure such as knee arthroplasty. Older patients tend to be more complex, so we gathered patient age from hospital records. Patients with low levels of overall health also tend to be more complex, so we assessed overall health in the patient survey using the overall health measure from the SF36 (Stewart, Hayes and Ware, 1988). These measures of complexity were considered separately for their potential impact on the modularity of care. Patient Outcomes We used a single item measure of patient satisfaction based on the question: Overall, how would you rate your care in the past six weeks?, and a single item measure of willingness to recommend based on the question: Would you recommend these healthcare providers to your family and friends?, both measured at six-weeks post-surgery. We also measured the quality of clinical outcomes. The two key clinical outcomes expected from joint replacement surgery are reduced joint pain and increased joint mobility. Percent reduction in joint pain was constructed by comparing post-operative reports on joint 12 pain to pre-operative reports, using patient surveys conducted prior to surgery and twelve weeks postsurgery. Percent improvement in joint functioning was constructed similarly. The survey questions included five items relating to pain and seventeen items relating to mobility from the WOMAC, a validated self-administered osteoarthritis instrument (Bellamy, et al, 1988). The survey questions asked about the amount of pain and degree of difficulty with mobility (five potential responses from none to severe) experienced in the past 48 hours during common activities. To minimize missing values, responses were included for all patients who completed at least eighty percent of the items in each of the indices. The mean of the non-missing values for each item was assigned to missing values for that item. Analyses Using the technique originally developed by Shepard (1981) and further refined by Eppinger and his colleagues (Eppinger, et al, 1994; Sosa, et al, 2003), we formed a matrix to find the patterns of ties within and across stages of the work process. We formed a matrix with the three different stages of care – acute, rehab and home – down one side, and the same stages of care across the top. We added a final row and column for those who were expected to play the system integrator role. Because we surveyed 8 provider types about their coordination with 14 provider types, our matrix is asymmetric. Observations about the 6 provider types that were not surveyed are reported only from the perspective of others, not from their own perspective. Still, all coordination ties in the matrix are measured from the perspective of at least one of the two providers in each relationship. In each cell of the matrix is the mean level of relational coordination on a 5-point scale, reported by the provider type along the left axis with respect to the provider type along the top axis, regarding the particular patient about whose coordination the provider was being surveyed. Once the matrix was complete, with all available survey responses reflected on it, we observed the patterns of relational coordination. According to our first hypothesis, we expected the three stages of care to display relatively high levels of relational coordination internally, and relatively low levels of relational coordination with each other. Hypothesis 1 was tested by comparing the mean level of relational coordination within modules to 13 the mean level of relational coordination between modules, and conducting a t-test for significance of differences between the means. According to our second hypothesis, we expected that the patient’s primary care physician, the managed care case manager, and the informal care provider would display relatively integrative patterns of coordination with the patient’s providers at each stage of care. Our second hypothesis is supported if the relational coordination found between the system integrators and the modules is significantly higher than the relational coordination found between the modules themselves. Hypothesis 2 was tested by comparing the mean level of relational coordination between system integrators and each of the modules to the mean level of relational coordination between the modules, and conducting a t-test for significance of differences between the means. To explore our third hypothesis regarding the impact of patient complexity on modularity, we divided the patient sample into higher and lower complexity based first on age, then on overall health. Then, we compared the mean levels of relational coordination within modules, between modules, and with system integrators. Hypothesis 3a is supported if relational coordination within modules and with system integrators is stronger for more complex patients, while relational coordination between modules is weaker or does not change. The alternative Hypothesis 3b is supported if relational coordination between modules is stronger for more complex patients, while relational coordination within modules and with system integrators is weaker or does not change. We tested both hypotheses by comparing the mean levels of relational coordination for more complex patients, to mean levels of relational coordination for less complex patients, and conducting t-tests for significance of differences between the means. Patient outcomes models require large numbers of observations to find significant effects, given unmeasured sources of variation across patients. Because the patients who responded to our surveys often did not have providers who responded and vice versa, our matched sample of patients and providers is not large enough to test for significant effects of relational coordination on patient outcomes. However, previous studies have shown significant positive effects of relational coordination on quality and efficiency outcomes in airlines (Gittell, 2001) and hospitals (Gittell, et al, 2000). For this study, we 14 simply compare mean performance outcomes for more complex patients, to mean performance outcomes for less complex patients, and conduct t-tests for significance of differences between the means. FINDINGS Modular Patterns of Coordination Table 3 shows a "dependency structure matrix," using coordination data from the process of patient care for knee replacement patients. Each cell of this matrix includes the mean level of relational coordination reported by the provider type listed in the left-hand column, with the provider type listed in the top row. The number of provider survey responses included in that mean is shown in each cell, in parentheses. Only responses about the providers a patient was known to have were included. Let us first consider an example of “within stage” or “within module” coordination. In the second row of the table, first column, we see that 80 acute physical therapists responded about their coordination of care with the acute physician regarding a patient in our study. The mean level of relational coordination that they reported with the acute physician was 3.4 on a 5-point scale. Both the acute physical therapist and the acute physician work at the acute stage of care, so this is an example of “within module” coordination. Let us now consider an example of “between stage” or “between module” coordination. Looking further along that same row at the fourth column, we see that 39 acute physical therapists responded about their coordination of care with the rehab physician regarding a patient in our study. The difference between the 80 responses and the 39 responses is due to the fact that about half of the patients in our study went from acute to rehab before receiving home care while the other half went directly from acute care to home care. We see that the mean level of relational coordination that acute physical therapists reported with the rehab physician was 1.1 on a 5-point scale. The acute physical therapist works at the acute stage of care, while the rehab physician works at the rehab stage of care, so this is an example of “between module” coordination. [Insert Table 3 about here.] 15 Looking at the entire matrix, we can see that all of the shaded cells on the diagonal represent within module coordination, all of the unshaded cells represent between module coordination, and all of the shaded cells along the bottom and far right column represent coordination by system integrators. According to Hypothesis 1, we should expect the shaded cells on the diagonal to have higher levels of relational coordination than the unshaded cells. Consistent with this hypothesis, the matrix shows clear evidence of modular coordination patterns. We see that all of the shaded cells (within module) have levels of relational coordination that are greater than 3 on a 5-point scale, while nearly all of the unshaded cells (between module) have levels of relational coordination that are less than 3 on a 5-point scale. There is one exception – physical therapists at the home stage of care report unexpectedly high levels of relational coordination with the physician at the acute stage of care. Table 4 compares more systematically the average strength of coordination within modules and the average strength of coordination between modules. Mean relational coordination within modules is 4.0 on a 5-point scale, while mean relational coordination between modules is 2.3 on a 5-point scale. This difference is significant at the 0.001 level. [Insert Table 4 about here.] Modularity theory also leads us to expect system integrators to have relatively strong ties with each module in the process. According to Hypothesis 2, we should expect the shaded cells along the bottom and far right hand column of Table 3 to have higher levels of relational coordination than the unshaded cells. This expectation is only partially met. We see that only the informal caregiver has strong ties (greater than 3 on a 5-point scale) with at least one provider in each module. The primary care physician has no strong ties with anybody, and the managed care case manager has relatively strong ties only with the acute case manager and the rehab case manager. Table 4 compares more systematically the average strength of coordination between modules and the average strength of coordination with system integrators. Mean relational coordination between modules is 2.3 on a 5-point scale, while mean relational coordination with system integrators is 2.6 on a 5-point scale. This difference is significant at the 0.001 level. Hypothesis 2 therefore receives support in 16 these data. However, as we saw from the disaggregated data on Table 3, the system integrator role is not played consistently by all of the parties who were expected to play it. The unanticipated finding is that the informal caregiver plays the lion’s share of this role. Implications of this finding will be explored below. Excerpts from interview data help flesh out and illustrate these quantitative results. One interview was selected from each of the three stages of care – acute, rehab and home. Excerpts were then selected from the three interviews to illustrate the different types of coordination: coordination internal to that stage of care, coordination with other stages of care, and coordination with system integrators. These results are summarized in Table 5. Several observations from these interviews are worth noting. First, we see evidence of a highly formalized set of protocols and forms for handing off patient information from one stage of care to the next, with little conversation or discussion required, from the perspective of the interviewees. Second, we see evidence of frequent conversations and discussions regarding the care of a particular patient among providers who work within a particular stage of care, and the stated belief that this is good and necessary. Third, we see a mixed picture of the role played by system integrators. The informal caregiver is seen as playing an essential role, while the primary care physician’s coordination role is seen either as unimportant or as important but unreliable. [Insert Table 5 about here.] Effect of Complexity on Modular Patterns of Coordination Next, let us see what happens to these modular patterns of coordination when we consider complexity of the patient. According to the theory of modularity, patterns of coordination should be more modular for more complex patients (Hypothesis 3a), while competing theories argue that modularity becomes less effective as complexity increases (Hypothesis 3b). The data presented on Table 6 show clearly that modularization increases rather than decreases with complexity of the patient. Relational coordination for older patients is significantly higher within modules (p=0.015) and with two of the system integrators (p=0.034 and p=0.001), while there is no significant increase in relational coordination between modules (p=0.430). Relational coordination for sicker patients is marginally higher within 17 modules (p=0.067) and with two of the system integrators (p=0.011 and p=0.004), while again there is no significant increase in relational coordination between modules (p=0.181). [Insert Table 6 about here.] In the language of design structure matrices, between module coordination does not become more extensive for more complex patients – rather the response to complexity is to increase coordination within the modules and to increase coordination between the modules and the system integrators. Interestingly, even though two of the system integrators (primary care physicians and managed care case managers) show limited evidence of strong coordination ties with the modules, they do show an increase in coordination for more complex patients. Taken together, these results suggest that patterns of coordination in healthcare are distinctly modular, and that this modularity is even more pronounced for more complex patients. There is no direct evidence about the benefits or drawbacks of this increased modularity for more complex patients. On the positive side, we observe that outcomes for patients in this study were quite favorable overall. Patients in this study reported an average 67 percent improvement in joint pain levels and 81 percent improvement in joint mobility levels by 12 weeks post-surgery, relative to pre-surgery. Furthermore, 83 percent of patients rated their care as excellent or very good, while 76 percent of patients reported that they were highly likely to recommend their care providers to others, and another 21 percent of patients were somewhat likely to recommend. On the negative side, however, we observe that more complex patients experienced somewhat lower outcomes than less complex patients. As shown on Table 7, older patients were marginally less satisfied with their care (p=0.061) and less likely to recommend their care providers to others (p=0.013) but their clinical outcomes were the same as for younger patients. Sicker patients (those who started out with lower overall levels of health) were significantly less satisfied with their care (p=0.024), marginally less likely to recommend it to others (p=0.071) and achieved marginally smaller improvements in joint pain (p=0.062). We do not know however if the satisfaction and clinical outcomes achieved by more complex patients would have been comparable to those for less complex patients if their care were delivered in a less modular way. 18 [Insert Table 7 about here.] DISCUSSION We conclude that modularization does exist in the current healthcare delivery system, with patterns that are quite similar to those previously found in other industries. One aspect of modularization is high levels of relational coordination within modules. By allowing relational forms of coordination to be relatively weak with providers who work at other stages of care, providers can focus on coordinating patient care with others at their own stage of care. The expectation is an overall positive effect on outcomes, if indeed the modules have been formed with the strongest task interdependencies within the modules, and the weakest task interdependencies between the modules. We also have seen that system integrators do indeed play a role in this industry, as they are expected to do under conditions of modularity (Sosa, et al, 2003). However, the system integrator role is played quite unevenly by the different parties. We see that neither the managed care case manager nor the primary care physicians play an extensive system integrator role. The managed care case manager has strong ties only with the case manager at the acute stage of care, and ties that are fairly strong with case managers at the rehab stage of care. The only ties for the primary care physician that approach our definition of strong ties (greater than 3 on a 5-point scale) are with the physician at the acute stage of care. Our results do show that both the primary care physician and the managed care case manager increase their role in coordination when the patient in question is older or sicker. However, the role still remains very weak (1.9 for the primary care physician and 2 to 2.3 for the managed care case manager, on a 5point scale). These findings call for investigation into the roles of the managed care case manager and in particular, into the primary care physician’s intended role as gatekeeper and coordinator of care. The primary care physician is typically not compensated for care coordination, and anecdotal evidence suggests that they neglect it due to intense pressures to see more patients in less time. Some health plans, however, such as Harvard Vanguard, have begun to compensate primary care physicians for their role in coordination and to include coordination of care as one of their performance metrics. 19 We find that the system integrator role is played most extensively by the informal caregiver who has strong ties (greater than 3 on a 5-point scale) with each stage of care. This is an important finding because while many studies have already documented the amount and kinds of care provided by informal caregivers (e.g., Lyons and Zarit, 1999; Donelan, et al, 2002), this study documents the significant role that they are playing in the coordination of care relative to paid providers. Given the lack of systematic training for informal caregivers and the highly unequal resources that different individuals can bring to this role, this finding is a cause for concern. Some families have highly educated members, while others have none, and many informal caregivers are themselves frail and elderly. These results suggest the need to consider the coordination role that is played by informal caregivers in a modular healthcare system and its impact on both caregiver and patient well being, and to support this role with more active involvement by paid caregivers including potentially the primary care physician. Finally, we have seen that patients who are more complex receive care that is more, rather than less, modular – that is, relational forms of coordination become stronger within modules and with system integrators, while relational coordination between modules remains the same. However, we do not know if this increased modularization for more complex patients is positive or negative. Indeed, the primary limitation of this study is the lack of sufficient sample size to test the performance effects of modularity. Numerous studies have found evidence to support the theoretical proposition that relational forms of coordination improve the quality and efficiency of patient care (e.g., Baggs, et al, 1992; Shortell, et al, 1994; Young, et al, 2000; Gittell, et al, 2000) and moreover have shown that these forms of coordination become more important, the more complex and uncertain the inputs to the work process (Argote, 1982; Gittell, 2002). However, these findings have not been replicated for coordination between distinct stages of care. Although we have documented the modularity of coordination in healthcare, the greater modularity for more complex patients, and the marginally poorer outcomes for those patients, we cannot answer definitively the question of whether modularity is beneficial in this setting, and whether the adaptations to the needs of more complex patients that we observed were adequate. 20 Modularity theorists suggest that modularity is an effective response to complexity, because it helps to reduce complexity by simplifying the interfaces between modules and enables those who are working within each module to better focus their efforts on the critical task interdependencies within. Coordination theorists and critics of modularity have argued instead that complexity calls for more integrative patterns of coordination, rather than for simplification of the interfaces. Our results suggest a potential reconciliation between these arguments, via the role played by system integrators. Modularity theorists have noted the role that system integrators play in modular systems (Sosa, et al, 2003); arguably, this role should increase as complexity increases. An increased role for system integrators could be a way to provide the higher bandwidth needed for effective coordination of complex work processes, according to coordination theorists (Daft and Lengel, 1986), and to provide the collaborative interface that is required for learning, according to the critics of modularity (Sabel and Zeitlin, 2004). One theoretical contribution of this paper, therefore, is a potential reconciliation between the argument that modularity is an effective response to complexity and the argument that the effectiveness of modularity is limited by complexity. Complexity can potentially be handled without increasing direct interfaces between the modules, so long as coordination by system integrators increases sufficiently to meet the need for higher bandwidth. More generally, this study extends the literature on patterns of work group interaction by helping us to answer the question: where should ties be relatively strong and where can they be relatively weak? As we noted at the start of this paper, if it is not feasible to build strong ties with every person who is engaged in the same work process (for example, working with the same patient), the question of how to best focus one’s limited time and attention on developing strong ties where they really matter becomes relevant. The results presented here suggest that modularized work processes may provide an answer to this question, so long as system integrators are equipped and encouraged to play an expanded role as complexity increases. 21 REFERENCES Argote, L. 1982. “Input Uncertainty and Organizational Coordination in Hospital Emergency Unit,” Administrative Science Quarterly, 27: 420-434. Arias, E.G. and Fischer, G. 2000. “Boundary Objects: Their Role in Articulating the Task at Hand and Making Information Relevant to It,” Intelligent Systems and Applications, pp. 1-8. Argote, L., M.E. Turner and M. Fichman. 1989. “To Centralize or Not to Centralize: The Effects of Uncertainty and Threat on Group Structure and Performance,” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 43(1): 58-75. Baggs, J.G., S.A. Ryan, C.E. Phelps, J.F. Richseon and J.E. Johnson. 1992. “The Association between Interdisciplinary Collaboration and Patient Outcomes in a Medical Intensive Care Unit,” Heart and Lung, 21: 18-24. Baldwin, C.Y. and K.B. Clark. 2004. Modularity in the Design of Complex Engineering Systems. Working Paper. ----------------------------------. 2000. Design Rules, Volume 1. The Power of Modularity. MIT Press: Cambridge, MA. Bavelas, A. 1950. “Communication Patterns in Task-Oriented Groups,” Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 22: 725-730. Bellamy, N., W.W. Buchanan, C.H. Goldsmith, C.H., J. Campbell and L.W. Stitt. 1988. “Validation Study of the WOMAC: A Health Status Instrument for Measuring Clinically-Important Patient Relevant Outcomes Following Total Hip or Knee Joint Replacement in Osteoarthritis,” Journal of Orthopedic Rheumatology, 1:95-108. Bohmer, Richard. 1998. “Critical Pathways at Massachusetts General Hospital,” Journal of Vascular Surgery, 28: 373-7. Brown, T.M. and C.E. Miller. 2000. “Communication Networks in Task-Performing Groups: Effects of Task Complexity, Time Pressure, and Interpersonal Dominance,” Small Group Research. 31(2): 131-157. 22 Cummings, J.N. and R. Cross. 2003. “Structural Properties of Work Groups and their Consequences for Performance,” Social Networks, 25(3): 197-210. Daft, R.L. and R.H. Lengel. 1986. “Organizational Information Requirements, Media Richness and Structural Design,” Management Science. 32(5): 554-571. Design Structure Matrix Home Page. 2005. http://www.dsmweb.org/. Donelan, K., C.A. Hill, et al. 2002. “Challenged to Care: Informal Caregivers in a Changing Health System,” Health Affairs. 21(4). Eppinger, S.D., D.E. Whitney, R.P. Smith and D.A. Gebala. 1994. “A Model-Based Method for Organizing Tasks in Product Development,” Journal of Engineering Design, 2: 283-290. Galbraith, J. 1995. Competing with Flexible Lateral Organizations. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. Gittell, J.H. 2005. “Relational Coordination: Coordinating Work through Relationships of Shared Goals, Shared Knowledge and Mutual Respect,” in Relational Perspectives in Organization Studies, (eds.) O. Kyriakidou and M. Ozbilgin. Edward Elgar Publishers. ---------------- 2002. “Coordinating Mechanisms in Care Provider Groups: Relational Coordination as a Mediator and Input Uncertainty as a Moderator of Performance Effects,” Management Science, 4811: 1408-1426. -----------------. 2001. “ ---------------- and L. Weiss. 2004. “Coordination Networks Within and Across Organizations: A MultiLevel Framework,” Journal of Management Studies, 41(1): 127-153. ------------------, K. Fairfield, B. Bierbaum, R. Jackson, M. Kelly, R. Laskin, S. Lipson, J. Siliski, T. Thornhill and J. Zuckerman. 2000. “Impact of Relational Coordination on Quality of Care, PostOperative Pain and Functioning, and Length of Stay: A Nine Hospital Study of Surgical Patients,” Medical Care, 38(8): 807-819. Grandori, A. and Soda, G. 1995. “Inter-Firm Networks: Antecedents, Mechanisms and Forms,” Organization Studies, 16(2): 183-214. 23 Helper, S., MacDuffie, J.P. and Sabel, C.F. 2003. “Pragmatic Collaborations: Advancing Knowledge While Controlling Opportunism,” Industrial and Corporate Change, 9: 443-83. Kirk, S., and C. Glendinning. 1998. “Trends in Community Care and Patient Participation: Implications for the Roles Of Informal Carers and Community Nurses in The United Kingdom,” Journal of Advanced Nursing, 28(2), 370-381. Langlois, R.N. 2002. “Modularity in Technology and Organization,” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization. 49: 19-37. Leavitt, H. 1951. “Some Effects of Certain Communication Patterns on Group Performance,” Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 46: 38-50. Lievens, A. 2000. “Project Team Communication in Financial Service Innovation.” Journal of Management Studies, 37(5): 733-767. Lusenhop, R. W., D.B. Weinberg, J.H. Gittell and C.M. Kautz. 2005. The Effects of Coordination on Informal Caregiver and Patient Outcomes Following Knee Replacement Surgery, Working Paper. Lyons, K.S. and S.H. Zarit. 1999. “Formal and Informal Support: The Great Divide,” International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 14: 183-196. Malone, T. and K. Crowston. 1994. “The Interdisciplinary Study of Coordination.” Computing Surveys. 26(1): 87-119. Monge, P.R. and N.S. Contractor. 2001. “The Emergence of Communication Networks.” F.M. Jablin, L.L. Putnam, eds. The New Handbook of Organizational Communication: Advances in Theory, Research, and Methods. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA, 440-502. Nunnally, J. 1978. Psychometric Theory. New York: McGraw-Hill. Perlow, L., J.H. Gittell and N. Katz. 2004. “Contextualizing Patterns of Work Group Interaction: Toward a Nested Theory of Structuration,” Organization Science. 15(3). Powell, W. 1990. "Neither Market nor Hierarchy: Network Forms of Organization," Research in Organizational Behavior. 12:295-336. 24 Sabel, C. and J. Zeitlin. 2004. “Neither Modularity Nor Relational Contracting: Inter-Firm Collaboration in the New Economy,” Enterprise and Society. 5(3). Shaw, M.E. and G.H. Rothschild. 1956. “Some Effects of Prolonged Experience in Communication Nets,” Journal of Applied Psychology. 40: 218-286. Sparrowe, R.T., R.C. Liden, S.J. Wayne and M.L. Kraimer. 2001. “Social Networks and the Performance of Individuals and Groups,” Academy of Management Journal. 44(2): 316-325. Shortell, S., J.E. Zimmerman, D. Rousseau, et al. 1994. “The Performance of Intensive Care Units: Does Good Management Make a Difference?” Medical Care, 32: 508-525. Sosa, M.E., S.D. Eppinger and C.M. Rowles. 2003. “Identifying Modular and Integrative Systems and Their Impact on Design Team Interaction,” Journal of Mechanical Design, 125: 240-252. Steward, D. 1981. “The Design Structure Matrix: A Method for Managing the Design of Complex Systems,” IEEE Transactions Engineering Management, 28(3): 71-74. Stewart, A.L., R.D. Hays and J.E. Ware. 1987. “The MOS 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36): Conceptual Framework and Item Selection,” Medical Care, 26: 724-35. Stille, C. J., A. Jerant, D. Bell, D. Meltzer and J.G. Elmore. 2005. “Coordinating Care across Diseases, Settings, and Clinicians: A Key Role for the Generalist in Practice,” Annals of Internal Medicine, 142(8): 700-708. Thompson, J.D. 1967. Organizations in Action. New York: McGraw-Hill. Von Hippel, E. 1990. “Task Partitioning: An Innovative Process Variable,” Research Policy, 9: 407-418. Wheelwright, S. 1995. “Massachusetts General Hospital: CABG Surgery,” Harvard Business School Case, 696-015. Young, G., M. Charns, et al. 2000. “Patterns of Coordination and Clinical Outcomes: Study of Surgical Services,” Health Services Research, 33: 1211-36. 25 Figure 1: Reciprocal Task Interdependencies Within Modules, and Sequential Task Interdependencies Between Modules Module A Module B Module C Acute Rehab Home Function x Function w Function x Function y Function w Function x Function y Function z Function z Function w Function y Function z Table 1: Providers Who Were Surveyed and About Coordination with Whom Providers Surveyed Stage of Care Acute Provider Type Physical Therapist Case Manager Rehab Physical Therapist Case Manager Home Nurse Physical Therapist System Integrator Primary Care Physician Informal Caregiver Each Was Surveyed About Coordination With Stage of Care Provider Type Acute Physician Physical Therapist Case Manager Physician Rehab Nurse Physical Therapist Case Manager Home Nurse Physical Therapist Case Manager System Integrator Physician Informal Caregiver Managed Care Case Mgr Table 2: Correlation Matrix 1. RC within stages of care 2. RC between stages of care 3. RC with system integrators 4. Patient age (1=high, 0=low) 5. Patient health (1=high, 0=low) 6. Satisfaction with care 7. Willingness to recommend 8. Improvement in joint pain 9. Improvement in functioning Mean (SD) 4.0 (1.01) 2.3 (.98) 2.6 (1.14) .20 (.40) .40 (.49) 4.3 (.83) 4.5 (1.03) .67 (.78) .81 (1.24) Obs 1. 334 -- 334 .146 (.007) .258 (.000) .131 (.015) -.099 (.067) -.055 (.355) -.058 (.355) .001 (.984) -.108 (.087) 336 201 197 161 154 154 147 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. -.546 (.000) .043 (.429) -.073 (.181) -.069 (.257) -.034 (.587) -.047 (.468) -.024 (.702) -.075 (.162) -.052 (.340) -.048 (.425) -.012 (.851) -.070 (.283) .004 (.953) --.071 (.110) -.121 (.013) -.141 (.005) -.109 (.035) -.089 (.080) -.213 (.000) .166 (.001) .186 (.000) .144 (.005) -.904 (.000) -.074 (.174) -.063 (.240) --.090 (.107) -.064 (.240) -.679 (.000) -- Table 3: Modular Patterns of Relational Coordination1 Physician Acute Rehab Home System Integrator 1 Acute Case manager Physical therapist Physician Rehab Nurse Case manager Physical therapist Home Nurse Physical therapist System Integrator Primary Informal Managed care care care case physician giver manager Case manager 3.5 (35) --- 4.3 (34) 1.1 (21) 2.2 (23) 2.6 (23) 2.3 (23) 2.5 (29) 2.2 (33) 2.5 (34) 3.6 (34) 3.9 (29) Physical therapist 3.4 (80) 3.8 (75) 4.1 (45) 1.1 (39) 1.2 (39) 1.1 (38) 1.4 (39) 1.1 (67) 1.3 (65) 1.1 (73) 1.9 (72) 1.2 (37) Case manager 2.1 (36) 2.2 (35) 2.0 (35) 3.6 (35) 4.3 (35) 4.5 (41) 4.4 (35) 2.3 (28) 1.9 (29) 1.8 (33) 3.3 (34) 2.7 (21) Physical therapist 2.3 (41) 1.7 (41) 2.1 (41) 3.8 (41) 4.2 (41) 4.2 (41) 4.6 (31) 1.5 (29) 1.8 (33) 1.4 (39) 3.0 (39) 1.5 (21) Nurse 2.8 (68) 1.5 (63) 1.3 (64) 1.2 (32) 1.2 (32) 1.2 (32) 1.2 (31) 4.5 (37) 4.0 (67) 2.1 (65) 3.4 (66) 1.6 (33) Physical therapist 3.5 (89) 1.8 (81) 1.9 (85) 1.6 (44) 1.6 (44) 1.5 (44) 1.9 (43) 3.8 (84) 4.3 (25) 2.0 (87) 3.3 (87) 2.1 (40) Primary care physician Informal care giver 2.8 (50) 1.6 (46) 1.3 (49) 1.4 (24) 1.7 (24) 1.8 (20) 1.7 (21) 1.5 (44) 1.4 (45) --- 1.9 (45) 1.3 (30) 3.3 (120) 1.8 (111) 2.4 (114) 2.2 (60) 3.0 (60) 2.1 (59) 2.8 (60) 3.3 (100) 3.6 (103) 1.9 (114) --- 1.2 (56) Shaded areas indicate where strong ties were expected based on theory of modularity. Strength of ties is measured on a five point scale. Strong ties are defined as ties > 3, and are indicated in bold and underlined. Row labels indicate the types of care providers who were surveyed, and column headings indicate the types of care providers they were surveyed about. Number of respondents shown in parentheses in each cell. Table 4: Differences in Relational Coordination Within Stages, Between Stages and With System Integrators Within Stages of Care Between Stages of Care With System Integrators Relational Coordination 4.0 (1.01) 2.3 (.98) 2.6 (1.14) Observations 334 334 336 Within Stages > Between Stages With System Integrators > Between Stages (p-value) (p-value) 0.000 0.000 Table 5: What Care Providers Say About Coordination Within Stage, Between Stage and with System Integrators Acute Rehab Coordination Between Stages Q: What type of information do you have about the patients when they come to you? A: We have a past medical history, surgical history. We can look up and see what type of surgery they had. Usually the notes in the chart will say any complications or any differences in the care of a joint replacement. So we have access to pretty much all the information that’s available. Q: Is there information that maybe you don’t need but that you would like to have about the patients when they come to you? A: No, I think it’s pretty thorough. Q: And there are certain providers from whom you don’t receive the information that you need. A: Nope. Q: And what happens when they leave the hospital? A: We do a discharge evaluation and update the notes so that the outside facility will be able to see where the patient is presently and any instructions they have regarding the exercises or range of motion or anything that may be different or you know, per the normal protocol. Q: Do you have any communication with the facilities other than writing these notes? A: No. They can call us, but we don’t usually talk to them at all. Q: So how does the handoff occur? What kind of information do you get? A: Basically, we get a screening form. That screening form would have the patient’s basic information. What their general status is. …We get the date of the nurse’s screen, the date of the Coordination Within Stages Q: When and how does the communication usually take place [here]? A: We can usually textpage the resident to leave a note in the chart. With the care coordinators we usually talk to them directly or they can decide by looking at our progress notes. Q: Do you feel that you have enough opportunity to share information with other care providers? A: Yeah, definitely. …I feel like everyone’s helpful and everyone’s usually on the same page…. Q: And would you say that the physical therapists work well together as a team? A: Oh, definitely. Q: What about with the nurses? A: Yeah, I think there’s good communication. They usually give us a call if something that we need to do, or come check out the patient or make sure that they are on our list to be seen for the day, so I think that’s good. Q: So, would you say that when things are kind of standard, you don’t really need to talk to other members of the team as much? A: Ummmmh, we really still communicate with them, like the doctors still need to let us know that medically if everything’s going all right, and we still check with the care coordinator. Make sure that this is still the plan, that what they are having and working on as well. Q: Anyone that you need to interact with about the patient while they are [here] besides the family member, or the patient themselves? A: We have meetings continually. We have an interdisciplinary team meeting on every patient on Wednesdays, which includes PT, OT, social work, Coordination With System Integrators [Acute providers not questioned about their coordination with system integrators due to an oversight in the design of interview protocol.] Q: Anything that you need to, any interaction you need to have with the primary care physician? A: Because we use the surgeons’ precautions, we like to speak directly to the surgeon. The PCP we don’t have any contact with, because when they are here they are under the care of the house Home admission. Who is screening them. The name, date of birth, address, city, zip, phone, marital status, next of kin. Kind of the basic socioeconomic information. Medicare, Harvard, what their insurance is and what their back up insurance is. Then we get like a primary diagnosis, secondary diagnosis, past medical history, and basic current history. This is the chart review that the screening nurse would do…Medication, do they have an IV, what’s going into it? The things that we would kind of basically need to know. …Have they been seen by therapist, what would they estimate they will tolerate for therapy .…What I’ve found is these screens are good basic information to know what you are walking into. The other thing that we get when the patient arrives here is their discharge summary from the hospital. Q: Is there anything that consistently doesn’t go well, things that are typically missing, or difficult to get, …if you have to follow up? A: It’s rare, I mean, I rarely have to call... Q: When you are passing the patient on to the next stage of care, what do you have to send with them? A: I send a history… You know that basic 3-pager has social work on top, and rehab on the bottom … I always include past medical history, social history, weight-bearing status, current functional status, including like independent [sit leg] versus not, have they achieved what the range of motion is, if they haven’t, if a home CPM has been ordered. What equipment they have. You know, blah, blah, blah. Q: What kind of information do you get from the hospital that’s discharging them? A: Most of our patients come from the rehab [hospital] after a knee replacement, and what I will get is a referral, a three-page referral from the discharging agency, which is a page 1 that the physician has signed with the orders, the nursing, nurse managers, recreation. [We have a] daily morning meeting. …There is a review of all the patients. Q: Just a quick, is everyone moving along? A: Yup, it’s like a round. We have rounds. So we have managers go to that. We have PTs and OTs in the same office, and we continually chat daily. We [especially] talk about the patients on Tuesday. We talk about them all day long. We go through everything on Tuesday before the meeting and that’s mainly where we talk about the rehab frequency, what they need, equipment, so we’re on the same page. physician, who is a general practitioner. The general practitioner here would write the orders, change the medication, and do all of those pieces. Q: Right, now how about the family member? A: Always actively involved. I mean, sometimes if there is trouble, we’re getting someone in here. We have a very, not really a formal environment here. We like to foster more of a “hey, I’m the therapist. How are you doing? so and so.” I always tell the patient what the deal is, what’s going on, what to expect. If they have any questions, we encourage family members to come to rehab. Q: Right, because they are going to be supporting this when they get home. A: Unless they have a [special] situation that makes it not beneficial for the patient. … It’s just a judgment call. Sometimes people get in the way. (both laugh). We encourage it. We try things out and we try and encourage the family members to come on down, you know, we are a subacute floor, the rehab department is on the same floor. So it’s “come on down.” Q: When both you and a physical therapist are assigned to a patient in their home, is there any kind of communication between you? A: I always communicate with my physical therapists. Even if it’s just …, obviously if I have a concern, but even if it’s just “things are going well. This is my plan.” And I do that with the Q: Now, in terms of working with information or communication with the patient and their family? A: Most total knees are elderly, older adults and there may be other issues going on. There may be other, you know, congestive heart failure, maybe another diagnosis…Most people will have, if not a spouse, a son or a daughter who may be involved. 32 medications, the physical therapy orders and then the page 2 would be a nursing, kind of an idea of where the patient’s been, what they’ve been through, how they are doing, their ADLs [activities of daily living] and they will sometimes incorporate the hospital forms into that because this is the rehab now, giving me this information, and then the page three will be the PT/OT part of it. So I have that and then there’s a liaison in the rehab that works for our agency who will also give me a page or two of information that they would find helpful. So, they’ve got about five pages of information. And if they come from the hospital, we also would get a discharge summary which is much more in detail and sometimes that comes through the rehab, but not always. Q: So the discharge summary, meaning when they first left the acute care hospital, that was put together by the surgeon? A: Right. Q: Do you often have to call back to anyone, either at the rehab or the acute to clarify information or to update them on problems that have occurred? A: [Sometimes] we do. For instance if I had a patient who came out from rehab on coumadin, and the blood level was a little high, a little low, I might call to find out what the most recent coumadin dose was, or how about the INR’s that’s the blood results have been running in the facility, that sometimes is not clear. That’s not common, luckily I don’t spend a lot of time doing that. physical therapist very consistently. Q: So you each will develop a plan of care and then share it with each other typically? A: Yes, and sometimes one of us will be leaving, the other one will be showing up, so there’s that communication as well. But I’ve always had phone contact with my physical therapists and it works both ways. Q: And, it’s the same physical therapist assigned to a patient throughout that period or does that vary, because that seems like that would complicate things? A: It is always the same physical therapist and I am actually fortunate that the territory I cover I have the same one, sometimes two therapists so I work with them …. We work together very well. And are always in contact with each other. We have e-mail as well through our laptops that we utilize. And there’s definitely communication with our plan. Discharge plan is also another, Eileen has a scheduled visit for a day I don’t and I have a concern, I will ask her to please check on this or that …. So I would maybe try to plan a visit with somebody, like a main support, if the person lived alone. Like maybe have the son or daughter be available for the first visit. Where you just want to utilize the pill boxes, pre-filled with the medication in it. Q: Now, how about the PCP? A: You know, it’s very individual and it would be ideal if a PCP got some sort of, you know, this is what the patient has been through hospital course, so they have, because there are sometimes when I would have to go to their PCP and if they haven’t seen the patient, some people only see their PCP once a year. So that is sometimes a problem, and what I would do in that case is I usually encourage my patients at some point to make a follow up appointment so that the PCP will have an idea of what’s going on. ..The doctors in the hospital or the rehab may change the patient’s medication and I find a lot of patients are like “My doctor put me on this” and then the doctor in the rehab doesn’t even know them, puts them on something else because of an incident… I will always tell a patient in that position to touch base with your primary care physician... So I would say, who regulates your cardiac medication and then at that point, I would say, you need to touch base with them and set up an appointment because now, you’re home... They may change their insulin dose while they are in. …So in that case I would always say, you know, make a phone call, and some people are more in close touch with their PCP than others. 33 Table 6: Differences in Modularity by Complexity of Patient Relational Coordination Within Stages of Care Between Stages of Care With System Integrators With System Integrator 1 (Informal Care Giver) With System Integrator 2 (Primary Care Physician) With System Integrator 3 (Managed Care Case Manager) Patient age < 75 3.9 (1.05) 2.2 (.99) 2.6 (1.15) 2.8 (1.38) 1.8 (1.11) 1.7 (1.21) Patient age > 75 4.2 (.79) 2.3 (.94) 2.8 (1.11) 3.2 (1.33) 1.9 (1.07) 2.3 (1.48) P-value 0.015 0.430 0.162 0.034 0.235 0.001 343 343 346 378 451 267 Patient health = good or excellent 3.9 (1.06) 2.2 (.96) 2.6 (1.15) 2.8 (1.40) 1.6 (1.01) 1.5 (1.06) Patient health = fair or poor 4.2 (.72) 2.3 (.99) 2.7 (1.14) 3.0 (1.37) 1.9 (1.15) 2.0 (1.40) P-value 0.067 0.181 0.340 0.131 0.011 0.004 343 338 341 373 444 262 Observations Observations 34 Table 7: Differences in Patient Outcomes by Complexity of Patient Satisfaction with Care Willingness to Recommend 4.6 (.91) Percent Improvement in Pain .70 (.78) Percent Improvement in Functioning .83 (1.25) Patient age < 75 4.4 (.82) Patient age > 75 4.1 (.88) 4.0 (1.41) .58 (.78) .71 (1.20) P-value 0.061 0.013 0.437 0.618 Observations 161 154 147 152 Patient health = good or excellent 4.5 (.80) 4.6 (1.00) .81 (.66) .98 (1.64) Patient health = fair or poor 4.2 (.84) 4.3 (1.05) .57 (.91) .68 (.86) P-value 0.024 0.071 0.062 0.148 158 155 146 150 Observations 35