Document 11612287

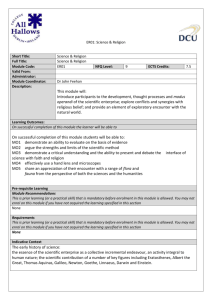

advertisement