Prevention for a Healthier America: INVESTMENTS IN DISEASE PREVENTION YIELD SIGNIFICANT SAVINGS,

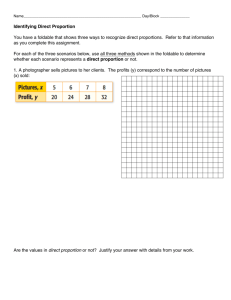

advertisement