Mycological Society of America

advertisement

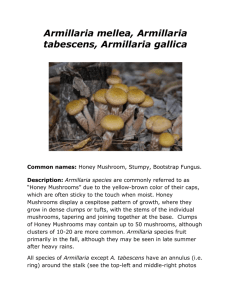

Mycological Society of America Identification of Armillaria Species from New Hampshire Author(s): T. C. Harrington and D. M. Rizzo Source: Mycologia, Vol. 85, No. 3 (May - Jun., 1993), pp. 365-368 Published by: Mycological Society of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3760697 . Accessed: 02/03/2011 19:25 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at . http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=mysa. . Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org. Mycological Society of America is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Mycologia. http://www.jstor.org Mycologia, 85(3), 1993, pp. 365-368. ? 1993, by The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY 10458-5126 BRIEF IDENTIFICATION ARTICLE OF ARMILLARIA SPECIES FROM NEW HAMPSHIRE T. C. Harrington Department of Plant Pathology, Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa 50011 AND D. M. Rizzo Department of Plant Pathology, University of Minnesota, St. Paul, Minnesota 55108 In 1979 Anderson and Ullrich proposed that Armillaria mellea sensu lato in North America be recognized as 10 biological species (Anderson and Ullrich, 1979). Although basidiome morphology was not compared, the biological species could be identified by compatibility testing; single-basidiospore strains of a given biological spe? cies generally changed their cultural morphology when paired on artificial media (Korhonen, 1978). Compatibility relationships and morphology of these biological species have been further investigated in North America, Europe and elsewhere (Watling et al., 1991). Six biological species found in eastern North America have been related to European species of Armillaria (Anderson et al., 1980; Watling et al., 1991) or described as new species (Berube and Dessureault, 1988, 1989). Ar? Because of difnculties in identification, millaria species found in eastern North America have not been extensively characterized, but indications are that they vary greatly in pathogenicity, in host specificity, and in the production of rhizomorphs (Berube and Dessureault, 1988, 1989; Blodgett and Worrall, 1992a, b; Dumas, 1988; Gregory et al., 1991; Rizzo and Harring? ton, 1993). We have identified six species of Ar? millaria in New Hampshire. Herein we record the hosts and distributions for five of these spe? cies. Basidiomes, mycelial fans, decayed wood and rhizomorphs of Armillaria were collected wherever encountered in the state from 1983 to 1990. These collections were not made systematically but, rather, were haphazard collections, often as part of other field studies (e.g., Rizzo and Har? rington, 1988; Worrall and Harrington, 1988). Most of the collections were made in the White 365 Mountain National Forest of central New Hampshire (Grafton and Carroll Counties) and the seacoast area of southeastern New Hamp? shire (Rockingham and Strafford Counties). Mycelial fans, basidiome tissue, or decayed wood were axenically excised and placed on wa? ter agar, 1% malt extract agar (MEA), or MEA with 100 Mg/ml streptomycin sulfate and 4 fig/ ml benomyl 50WP added after autoclaving (BSMA) (Harrington et al., 1992). Rhizomorphs were surface-sterilized in 70% ethanol for a few seconds and rinsed in sterile distilled water prior to plating. Haploid strains derived from single basidiospores were obtained by dilution plating of spore masses from spore prints (Harrington et al., 1992). Isolation plates were incubated at 2025 C and subcultures stored at 4 C on MEA. All field isolates (putatively diploid) and single-basidiospore strains (putatively haploid) were identified to species by pairing on MEA with haploid tester strains of known Armillaria spe? cies (Harrington et al., 1992; Rizzo and Har? rington, 1992). The tester strains (Table I) were selected for flufry morphology and consistently changed morphology after pairing with diploid isolates or compatible haploid strains of the same species. Five species of Armillaria were identified from 74 collections: A. calvescens Berube & Dessureault, A. gallica Marxmiiller & Romagn., A. mellea (VahlrFr.) Kummer, A. ostoyae (Ro? magn.) Herink, and A. sinapina Berube & Dessureault (Table II). The 74 collections were associated with 19 host species (five coniferous species and 14 hardwood species). Two collec? tions were not compatible with the testers and were not identified. 366 Mycologia Table I Haploid tester strains used to identify diploid field isolates and haploid strains of Armillaria a From J. J. Worrall. b From J. B. Anderson. Armillaria ostoyae was the most commonly encountered species (Table II); it was collected 52 times, from the northern part of the state south to the seacoast area, and from five coniferous and five hardwood species. Twelve ofthe collections were from basidiomes (either singlebasidiospore isolations or isolations from basidiome tissue), and 40 were from mycelial fans, decayed wood, or rhizomorphs. The majority of the collections were from red spruce (Picea rubens) or balsam fir (Abies balsamea). In these and other host species, the fungus usually appeared to be pathogenic because it occurred on a living or recently killed tree. Occasionally, A. ostoyae was found causing a root and butt rot of living trees, i.e., there was decay of the central xylem of roots and the butt without apparent colonization of the cambial region (Rizzo and Harrington, 1988). All eight records of A. mellea were from basidi? omes found in four mixed hardwood-conifer stands in the seacoast area. No samples of A. mellea were collected from inland sites. Four of the basidiomes were collected from well-decayed stumps or buried roots that could not be iden? tified to species (Table II). In four other cases, A. mellea was found killing roots and causing dieback on living Pinus strobus, Acer sp., Betula populifolia, or Quercus rubra. The apparent restricted range of A. mellea to the milder seacoast area is consistent with other records of its occurrence in milder regions of Michigan (Proffer et al., 1987), New York (Blodgett and Worrall, 1992a) and Europe (Kile et al., 1991). Armillaria sinapina was found three times, twice in central New Hampshire and once in extreme northern New Hampshire (Coos County). Two isolations were from rhizomorphs growing through advanced hardwood decay caused by other fungi. A third isolate was from a basidiome on a downed, well-decayed birch log. Armillaria gallica was found nine times on seven host species (Table II). It was recorded from five sites in the seacoast area and two sites in southcentral New Hampshire (Merrimack and Grafton Counties). Records of A. gallica in New York (Blodgett and Worrall, 1992a) were also primarily from the central and southern portions Brief Article 367 Table II Number of collections and host of origin of Armillaria of that state. Six ofthe isolates of A. gallica were from basidiomes on or under a living tree, on which it may have been pathogenic. Pathogenic colonization was likely in three cases where iso? lates were obtained from mycelial fans under the bark of two chlorotic Malus sp. from apple orchards and from a dead, ornamental Elaeagnus angustifolia. Armillaria calvescens was collected twice from two host species (Table II) in the northern hardwood forest type of the White Mountains. Both isolates were from mycelial fans on living trees, and the fungus appeared to be weakly pathogenic (attacking previously stressed trees). A sixth species, A. gemina Berube & Dessu? reault, not identified among the 74 isolates re? ported here, was found at an intensively studied site in central New Hampshire, at which an additional 130 Armillaria isolates were obtained. Detailed observations of host relationships of A. gemina, A. calvescens, and A. ostoyae at this site were reported previously (Rizzo and Harrington, 1993). As in many other surveys for Armillaria, an accurate portrayal of the distribution and hosts in New Hampshire was limited because of sam? rhi? pling bias. The abundance of basidiomes, zomorphs and mycelial fans of Armillaria species varies greatly among the species and among sites. species identified in New Hampshire Our search for basidiomes was largely confined to the White Mountains and the seacoast area. Other isolations were biased to the more pathogenic species, particularly A. ostoyae, and to red spruce and balsam fir because we preferentially sampled dying trees of these two host species in other studies. Given these limitations, it is somewhat surprising that we have identified all six Armillaria species of the northeast United States in the small state of New Hampshire. We thank J. B. Anderson and J. J. Worrall for providing some of the tester strains used in this survey. Also, D. Hobbins, M. L. Fairweather, K. J. Smereka and P. J. Zambino assisted in the collection of basidi? omes and other samples. We thank N. A. Anderson, R. A. Blanchette and J. J. Worrall for their helpful reviews of the manuscript. This material is based upon work supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, CSRS under Agreement No. 86-FSTY-9-0186. Journal Paper No. J-14951 of the Iowa Agriculture and Home Economics Experiment Station, Ames, Iowa Project No. 0159. Key Words: Armillaria, distribution, hosts, species identification LITERATURECITED Anderson, J. B., K. Korhonen, and R. C. Ullrich. 1980. Relationships between European and North American biological species of Armillaria mellea. Exp. Mycol. 4: 87-95. 368 Mycologia and R. C. Ullrich. 1979. Biological species of Armillaria mellea in North America. Mycologia 71: 402-414. Berube, J. A., and M. Dessureault. 1988. Morpho? logical characterization of Armillaria ostoyae and Armillaria sinapina sp. nov. Canad. J. Bot. 66: 2027-2034. 1989. Morphological studies of and-. -, the Armillaria mellea complex: two new species. A. gemina and A. calvescens. Mycologia 81: 216225. Blodgett, J. T., and J. J. Worrall. 1992a. Distributions and hosts of Armillaria species in New York. Pl.Dis. 76: 166-170. 1992b. Site relationships of Ar? and-. -, millaria species in New York. Pl. Dis. 76: 170? 174. Dumas, M. T. 1988. Biological species of Armillaria in the mixedwood forest of northen Ontario. Ca? nad. J. Forest Res. 18: 872-874. Gregory, S. C., J. Rishbeth, and C. G. Shaw, III. 1991. Pathogenicity and virulence. Pp. 76-87. In: Ar? millaria root disease. Eds., C. G. Shaw, III, and G. A. Kile. Agric. Handbook No. 691. USDA For? est Service, Washington, D.C. Harrington, T. C., J. J. Worrall, and F. A. Baker. 1992. Armillaria. Pp. 81-85. In: Methods for re? search on soilborne phytopathogenic fungi. Eds., L. L. Singleton, J. D. Mihail, and C. Rush. Amer? ican Phytopathological Society Press, St. Paul, Minnesota. -, Kile, G. A., G. I. McDonald, and J. W. Byler. 1991. Ecology and disease in natural forests. Pp. 102? 121. In: Armillaria root disease. Eds., C. G. Shaw, III, and G. A. Kile. Agric. Handbook No. 691. USDA Forest Service, Washington, D.C. Korhonen, K. 1978. Interfertility and clonal size in the Armillariella mellea complex. Karstenia 18: 31-42. Proffer, T. J., A. L. Jones, and G. R. Ehret. 1987. Biological species of Armillaria isolated from sour cherry orchards in Michigan. Phytopathology 11: 941-943. Rizzo, D. M., and T. C. Harrington. 1988. Root and butt rot fungi on balsam fir and red spruce in the White Mountains, New Hamsphire. Pl. Dis. 72: 329-331. 1992. Nuclear migration in dipand-. -, loid-haploid pairings of Armillaria ostoyae. My? cologia 84: 863-869. 1993. Delineation and biology -, and-. of clones of Armillaria ostoyae, A. calvescens and A. gemina. Mycologia 85: 164-174. Watling, R., G. A. Kile, and H. H. Burdsall, Jr. 1991. Nomenclature, taxonomy, and identification. Pp. 1-9. In: Armillaria root disease. Eds., C. G. Shaw, III, and G. A. Kile. Agric. Handbook No. 691. USDA Forest Service, Washington, D.C. Worrall, J. J., and T. C. Harrington. 1988. Etiology of canopy gaps in spruce-fir forests at Crawford Notch, New Hampshire. Canad. J. Forest Res. 18: 1463-1469.