Wikipedia and Global Development [TRANSCRIPT PREPARED FROM A TAPE RECORDING.]

advertisement

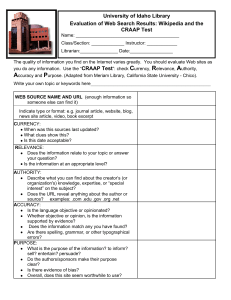

![Wikipedia and Global Development [TRANSCRIPT PREPARED FROM A TAPE RECORDING.]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/011586392_1-17d89b770305d70f944df24fc0921cf7-768x994.png)