The Prospects of Bringing a Green Revolution to Africa Norman Borlaug

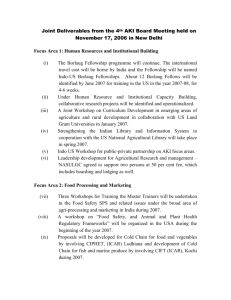

advertisement