MISSING THE MARK: GIRLS' EDUCATION AND THE WAY FORWARD

1

Center For Global Development

International Center for Research on Women

U.N. Millennium Project

MISSING THE MARK:

GIRLS' EDUCATION AND THE WAY FORWARD

Wednesday, March 2, 2005

Holiday Inn on the Hill

Federal Ballroom

Washington, D.C.

[TRANSCRIPT PREPARED FROM TAPE RECORDINGS.]

AGENDA

PAGE

WELCOME AND KEYNOTE SPEAKERS

Introduction and Welcome

Geeta Rao Gupta, President,

International Center for Research

On Women 4

Opening Remarks

Hon. Hilary Rodham Clinton

A U.S. Senator from New York 7

Opening Remarks

Jeffrey Sachs

Director, Earth Institute, Columbia

University; Director U.N. Millennium

Project and Special Advisor to

United Nations Secretary-General 13

Opening Remarks

Hon. Chuck Hagel

A U.S. Senator from Nebrasks 20

PANEL ONE: REACHING UNIVERSAL PRIMARY

EDUCATION AND GENDER PARITY: CHALLENGES

FOR NATIONAL GOVERNMENTS AND DONORS

Findings and Recommendations for the

Education Sector from the U.N. Millennium

Project Task Force on Education and

Gender Equity

Amina J. Ibrahim, Chair; National

Coordinator, Education for All, Nigeria 24

Experiences from Colombia

Vicky Colbert de Arboleda , Executive

Director, Escuela Nueva Back to the People

Foundation 27

Donor Challenges

Desmond Bermingham , U.K. Department for

International Development 29

Making the Donor Relationship Work

Elizabeth King , Research Manager,

Development Research Group, World Bank 32

2

AGENDA (Continued)

Closing Comments on Strategies for

Moving Forward

Nicholas Burnett, Director, Education

for All, Global Monitoring Report, UNESCO 39

PANEL TWO: GENDER PARITY: WHY SECONDARY

EDUCATION IS CRITICAL TO THE MDGS

Gender Equity Findings and Recommendations for Gender Equity from the U.N. Millennium

Project Task Force on Education and Gender

Equity

Geeta Rao Gupta , President,

International Center for Research on Women

Importance of Secondary Education

Cynthia Lloyd , Director of Social Science

42

Research, Population Council and Chair,

National Academy of Sciences Panel on

Transitions to Adulthood in Developing

Countries 46

Experiences from Bangladesh

Dilara Hafiz , Director of Secondary and

Higher Education, Ministry of Education,

Bangladesh 49

UNICEF'S Approach

Cream Wright , Chief, Education Section,

UNICEF 51

SYNTHESIS AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR MOVING

FORWARD

Importance of 2005; Ways to Move Forward

Gene Sperling , Director, Center for

Universal Education, Council on Foreign

Relations 58

Special Video Message

U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Anan 63

Final Closing Remarks

Nancy Birdsall, President, Center

for Global Development 63

3

4

P R O C E E D I N G S

INTRODUCTION AND WELCOME

MS. GUPTA : Good morning. I think we should begin because we have a tight schedule for the day.

My name is Geeta Rao Gupta, and I'm president of the International Center for

Research on Women, a policy institute here in the Washington, D.C. area that works to improve the economic, social, and health status of women living in poor communities around the world.

On behalf of the Center for Global Development, the U.N. Millennium Project, and ICRW, I welcome all of you to this very important event.

Among all the VIPs that we have among us today, we are thrilled to have with us members of the boards of directors of both CDG and ICRW. And I'd like to acknowledge them and would like them to stand and like all of you to join me in a round of applause, because board members are volunteers to institutions, and they give a lot in terms of both time and their support.

First of all, Ed Scott, founder and chair of CDG.

[Applause.]

J oined here also by his wife, Cheryl Scott, who has also been a great supporter of

CDG. Thank you.

[Applause.]

A nd Adam Waldman. Is he here? A member of the board of CDG? And we're expecting Brooke Shearer , who isn't here yet, who's a member of ICRW's board of directors. I thank you all for your leadership and support of our institutions.

I also want to acknowledge the presence of members of our task force. I understand Arlene Mitchell is here. Is she here? There she is. Thank you, Arlene, for your efforts towards the work that the task force produced.

Gene Sperling is here somewhere. I saw him earlier. Gene, are you here? He's outside getting coffee. And Simon Ellis, who wasn't an official member of the task force, but contributed greatly to our deliberations and contributions. Is Simon here? Hi, Simon.

Thank you.

As you all know, in September 2000, the world leaders from 189 countries endorsed the Millennium Declaration, from which were drawn eight Millennium

Development Goals.

The goals cover a wide range of development outcomes, including eradicating poverty and hunger, improving maternal and child health, containing infectious diseases, and protecting the environment.

What we are gathered here today to do is to focus on two of those goals. Goal

Number Two, which is to achieve universal primary education, and Goal Number Three, which is to promote gender equality and empower women.

Both goals are critical w believe for meeting all of the MDGs. Investments in gender equality and education are some of the smartest investments we as a global community can make.

They have the ability to bring about large-scale and transformative intergenerational changes in the lives of women, men, and children.

And that will be the focus of much of the discussion today. These goals, like all the other MDGs, are backed by concrete and measurable targets. And that's what makes the Millennium Development Goals somewhat different from promises made before.

5

Most of these targets are to be met by 2015, but with one exception. A part of the target for the goal in gender equality and the empowerment of women is to eliminate gender disparity in primary and secondary education by the year 2005.

And so here we are in the year 2005, the year when the first of the targets for the

MDGs falls due--an important moment we thought to remind the global community--all of us--donors, governments, representatives of civil society organizations--that we need to do a lot more to ensure that we meet this deadline, because although we have made substantial progress since the year 2000, it has been too slow to meet the 2005 target.

That is the purpose of this meeting, to draw attention to the need to accelerate progress toward the target of gender parity in primary and secondary education, by listening to the view of key stakeholders on what it will take to get the job done--if not by

2005, at least by 2015--and to meet this target at high levels of overall participation because gender parity in primary and secondary education can often be achieved with very small proportions of girls and boys in school. What we want to be able to do is achieve that goal at high levels of participation.

Today's panels will touch on many of these issues and the challenges that we face as we move ahead, but most importantly, we hope that the discussion will lead to suggestions of very specific ways that we can all move forward to achieve the goals because there is really no other way forward but to meet the promises that we have made.

This event was made possible because of the support of our donors--the United

Nations Foundation. Is Amy Weiss present here? Thank you so very much for your support.

The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation. Is Tamara Fox in the room? Perhaps not.

And the Nike Foundation, and I know that Maria Itel the president of the Nike

Foundation is with us in spirit, if not in person. And Magna International, who also couldn't be with us today, but has supported this effort.

So please join me in one more round of applause for these donors--

[Applause.]

Because I have to say it takes leadership on these issues to move these causes forward. I also want to mention that in support of another MDG, the one that seeks to contain the HIV/AIDS pandemic, the U.N. Foundation, one of our donors for today's event, is supporting, together with U.N. AIDS and other donors, a congressional breakfast on March 8th--this is a plug for the event--focusing on women and AIDS, because as you know, the face of the epidemic now is that of women, particularly young women. And because they're empowerment is key to containing the epidemic, I thought it was relevant to mention that that event is occurring on March 8th. And I think information on the event is available here today.

During the course of this morning, we will be outlining specific recommendations that were derived through a three-year long process of review, analysis, and discussion that was undertaken by the task force on education and gender equality, which was one of

10 task forces convened by the U.N. Millennium Project.

The U.N. Millennium Project is an independent advisory body commissioned by the U.N. Secretary-General to propose the best strategies to meet the MDGs. Its efforts are led by Professor Jeffrey Sachs. I must say an inspirational and committed leader, who's here with us today, and we're thrilled to have you here, Jeff. The task force on education and gender equality was co-chaired by Nancy Birdsall, the president of the

Center for Global Development, Amina Ibrahim, the national coordinator for the

Education for All Initiative in Nigeria, and by me.

6

And we worked closely with 30 members of our task force who consisted of researchers, civil society representatives, experts from U.N. organizations, representatives from donor agencies and national governments. All of us worked together to look at the data that is available in order to identify countries that are on track to meeting these targets and goals or off track; to examine best practices and success stories, and then vet various theories of social change and development to come up with key recommendations for meeting the goals for universal primary education and gender equality.

It has been a pleasure and a privilege to work with Amina and Nancy on this effort, and we were ably supported with incredible technical expertise and knowledge by two senior associates, Ruth Levine from CDG and Caren Grown from ICRW.

The task force also benefited greatly from the efforts of Chandrika Bahadur of the

Millennium Project. We are grateful for your efforts, Chandrika, and from staff, particularly support provided by Kelly Tobin of CDG and Aslihan of ICRW. In fact,

Kelly was instrumental in organizing today's event. Where are you, Kelly? Not in the room when she should be. And worked closely with Chandrika in the Millennium

Project secretariat and with the communications team at CDG and with Aslihan at ICRW to make today happen. So thank you to all of you.

I hope you have already seen that there are copies of the task forces' reports.

There are two reports, one on education, one on gender equality, that are available for you outside, as well as the overview report of the Millennium Project that was authored by all of the coordinators of the task forces, led by Jeffery Sachs.

We also have shorter versions of the task force reports that are available as policy briefs in your packets hopefully, or maybe out there at the table. And you may have also had a chance now to look at the agenda.

Let me just quickly walk you through that so we are clear what's happening.

We have three keynote speakers this morning, and Senator Clinton will be joining us shortly. And then we have three panels. One that's focused on UPE, universal primary education. Another that's focused on gender parity, with a specific focus on secondary education, and the third that looks at ways to move forward.

We anticipate if we are good in chairing these sessions that there will be plenty of time for discussion and debate and we hope and encourage all of you to participate.

We really thank you all for being here. We're looking forward to a very informative and energizing debate and discussion this morning. I should say that this is a timely discussion. I don't know if you're all aware but as we meet here today, civil society and government representatives from around the world are meeting in New York

City to mark the 10th anniversary of the Beijing Conference on Women, and to recommit to the promises made.

They are facing some hurdles in making that happen, but they are determined to make it happen, because, in fact, it is many of those promises that are encapsulated in the goals that we are discussing here today.

It's also important to remember that we are only six days from International

Women's Day, which is on March 8th. And, therefore, we thought that this might be a good time to meet and gather, not just to recommit to the idea of gender equality and the empowerment of women, but to commit to taking action to meet the goal within a specified period of time. That's what we'll be focusing on today.

And to the extent that each of you can participate in making sure that happens, please do so. Share with us experiences that you may have had through your work, either within international agencies or at the country level, in making sure that these goals are

7 met and any successes or learnings that you have had through your work would be important to today's discussion.

Frankly, we have only 10 more years. It is a golden opportunity for us to take action and move forward. If this window of opportunity is missed, I think it will be very difficult to get the global community to recommit in quite the same way. It will be impossible to chip away the cynicism that I know is already growing in the work in which we're all involved.

So I just want to urge you all to think of this as a golden opportunity and to believe that there is really no time to waste.

I don't know if Senator Clinton is here yet. Do you want to take a quick look and see? Any questions about the agenda or about the day's proceedings?

[Pause.]

So give us a minute just to find out where Senator Clinton is at, and we'll proceed.

[Pause.]

Okay. Senator Clinton is still a ways away. We didn't quite time it the way we thought we had, so I suggest that you engage with the person sitting next to you in conversation, and we'll wait 'til she arrives.

[Pause.]

Sure. Yes. Can everybody please take their seats? We need to clear the outside area for the Senator's arrival. We weren't so far off from our timing. Can I please urge you all to take a seat and settle down?

Like Senator Hilary Rodham Clinton. Ladies and gentlemen, Senator Clinton.

[Applause.]

OPENING REMARKS

SENATOR CLINTON: Thank you very much, and I am deeply honored to be speaking in front of such a group of committed individuals who have in many instances devoted your own lives to helping women and girls, and, in other instances, devoted considerable financial resources, personal and charitable and corporate.

But all of you are here because you share a deep and eternal belief that we have much work left to do with respect to equal rights, gender equality, and what that means for a future of stability, prosperity, and peace for our world.

There are so many people to thank here, and I'm looking out at this audience, and

I see many people with whom I have worked in the past, going back in some instances 30 years, and others five years, and then some less than that. But I am delighted that we have such a broad cross section of people for whom the issue of gender equality is a passion.

I want to thank Nancy Birdsall and Geeta Rao Gupta and Amina Ibrahim for making this conference and this task force a reality in so many ways.

I want to thank Jeffrey Sachs and the U.N. Millennium Project for convening the task force on the Millennium Development Goals, and this team is a real leadership example for raising this issue and not letting it go. And I'm grateful for that.

I know later today we'll by joined by Senator Hagel, and I'm delighted that he will be here addressing you.

And finally, I want to thank my long-time friend Gene Sperling for his commitment to this issue. Ever since President Clinton sent Gene I think to Senegal in

2000, he has been a tireless advocate on behalf of gender equality and particularly universal basic education.

You know for more than 30 years I have worked on behalf of girls and women's issues. And particularly during the Clinton Administration, I had the great honor of

8 traveling throughout our world, often with my husband, often on my own, sometimes with my daughter, representing our country, and whenever possible visiting schools, going into communities, seeing first-hand what was happening in the lives of girls and women.

I remember going to a school in Uganda after President Museveni had made the decision to eliminate school fees. That was a terrible idea that went into effect in the

1960s, '70s, and '80s, and it put up a barrier to universal education; and it was particularly hard on daughters, because with limited resources, so many families made what seemed to be a very practical choice of sending their sons to school and not their daughters. It was one of those horrible ideas that I guess made sense in some air-conditioned office in

Washington or London, but in the realities of the lives of human beings, it was absurd.

And there was such a gap of resources between what was available and what was needed that trying to instill personal responsibility, which is I guess the idea behind it, in families by making them pay fees to educate their children just was a failure. And unfortunately, it lasted far too long, and we lost one, probably two generations of children. And when President Museveni decided he was going to try to make it possible for children to attend school, he had an overwhelming response. There was enormous pent up demand to educate all children and particularly girls.

I went to a school that was literally packed to the gills. You could not have put one more chair or one more child into this space. There were 75 or 80 children. It was a room, maybe 15 by 20 feet. There was one teacher. There were no supplies. But there was an eagerness that was just palpable and very humbling.

You know I remember being in a village outside of Lahore, Pakistan, sitting under a tree, talking to women about the school that they had for their girls, which came about because of strong village support to have a school. It was a, you know, a concrete building in, you know, somewhat better equipped. There was a map on the wall. There were desks. There was a teacher, but this primary school, which was the limit for the education of their daughters, and it was roughly up to sixth grade, was a source of some controversy for the mothers, because they wanted their daughters to be able to go on to secondary education. But, of course, they couldn't because there weren't fund to build a secondary school for girls in the village and no respectable family would send their daughters off alone to go to school, so they were at a stalemate. And, you know, I remember being with these wonderful women and, you know, asking them, you know, was there anything we could do, and they said they would just keep trying to persuade the government and the village governing group, the elders, to really commit their resources to the aspirations of their daughters.

You know, I remember being in a village in Bangladesh, where one of the experiments we tried during the Clinton Administration was beginning, and that was to provide both cash payments and food commodities to families in return for their sending their goals to school. And talking to the village elders there, I was amazed at how many would be encouraged and could feel they were affording the luxury of educating their daughters in return for a bag of rice. But there had to be some ability that they then could do without the services, the family contributions, of their children, both at home and in the larger economy.

So all over the world, we've had examples of progress. But I think it's fair to say we know we have a very, very long way to go.

As all of you probably know, girls' primary school completion rates in Africa doubled between the 1960s and the late 1990s, and many developing countries

9 significantly increased their spending on education for boys and girls, especially in East

Asia and the Pacific, Latin America, and the Caribbean areas.

The number of out of school children of primary school age declined from 106.9 million in 1998 to 104 million in 2001, according to 2003 UNESCO report. In Brazil, for example, the literacy rate increased from 80.1 percent to 88 percent in just a decade. And the literacy rate for women is currently at 88.3 percent, and we can point to these areas of progress, but we have to come back to the rather daunting fact that we have 104 million children who are not attending primary school.

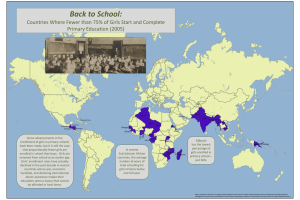

But 2005 is the year of the first United Nations Millennium Development goal, when gender parity in classrooms was supposed to be achieved. Unfortunately, at least

70 countries will miss the mark. They won't attain this goal this year. And so we need to do better, and we need to come up with strategies that will enable us to do better.

Of those 104 million who are out of school, 60 million are girls. The problem is most pronounced in sub Saharan Africa, where, despite the progress mentioned above, nearly 55 percent--so over half--of girls do not complete primary school.

According to the World Bank Education Advisory Services, an additional 150 million children worldwide are currently attending school but are at significant risk of dropping out before completing primary school. And failure to provide adequate education has real consequences for families, obviously for the individuals, but also for the global economy, for national advancement, for national security, and there's no way to put a dollar figure on the limitless potential that is lost because children are not able to be educated up to their God given potential.

Uneducated women are too easily and too commonly denied the basic social rights that we believe all people should have--the right to own property, to hold a job, access to credit, to cast a vote, or to, you know, better themselves through further education.

So to guarantee women equal rights and to make our world in my opinion more peaceful and secure, it is in everyone's interest to continue to try to meet the Millennium

Development Goals. And education must be the foundation of any strategy to do so.

Research shows that investment in girls' education is a critical necessity for a country's development. And it translates into higher incomes and better health. A single year--a single year--of primary education correlates with a 10 to 20 percent increase in women's wages later in life.

The impact of a year of secondary education is even higher, increasing expected wages by 15 to 25 percent. And educating girls contributes significantly to a nation's health. Girls' education is one of the best ways to combat the spread of HIV/AIDS. Girls make up three-quarters of infected young people in sub Saharan Africa. And in some countries, girls aged 15 to 19 are infected at five times the rates of boys.

According to a recent survey of the academic literature, girls' education is the best single policy for reducing fertility and achieving sustainable families. I remember sitting under that tree in that village outside of Lahore talking to a very feisty woman with 10 children, five boys, five girls. She had done everything to get her boys educated, and she was so upset that her girls couldn't have a similar opportunity. And she said if I had to do it differently, I wouldn't have had so many children, because then I could have fought harder for my girl children.

In Brazil, for example, illiterate mothers have an average of six children, while literate mothers chose to have less than three. And they are then better able to care for and invest in their children's wellbeing.

10

So I believe that we should focus on systemic reform and we should support countries that develop plans to put every child into school. And we need to address the overwhelming failure of education with a comprehensive global approach.

In the last Congress, I introduced the Education for All Act, which builds on the

Fast Track Initiative to promote systemic education reforms worldwide. I plan to reintroduce the bill in this Congress. And the bill calls for a development of a clear global strategy to achieve universal global education by the Millennium Development date of 2015. It encourages and helps to fund the necessary reforms in order to make this a reality.

The Act makes educating children globally a high priority of U.S. foreign policy, and it does this, in part, by dramatically increasing our investment in global education. It would be--assuming we could pass this bill and get it funded--$500 million the first year; a billion dollars the next; two billion a year by 2010.

My bill also calls for leveraging funds from non-governmental organizations, the private sector, and individuals.

Now I didn't propose to spend this much money in a vacuum. I coupled this resource commitment with strong accountability measures, which demonstrate to countries that if they step up to the plate, we will be there to back their efforts.

You know my bill requires countries to have a credible national education plan in place in order to receive funding. And the funding would be withheld if it turns out there is not adequate reform or sufficient accountability to make such statements with confidence.

I'm pleased we took a small step toward achieving universal global education with the 9/11 Implementation Act. I worked with my colleagues--Senators Lieberman and

McCain--to stress the importance of education to our national security. And thanks to this Act, by June of this year, the Administrator of USAID and the Secretary of State will jointly develop a strategy for promoting free universal basic education in Muslim countries. This strategy will include U.S. efforts to support education in general and will specifically focus on helping developing nations create national education plans. It includes a strategy to leverage resources from the G8 nations and other donors and a detailed plan to assist with the costs associated with making universal basic education available.

The 9/11 Implementation Act also authorizes an International Youth Opportunity

Fund, which will increase U.S. resources devoted to pursuing education in developing nations.

Now we've made some headway in U.S. funding for education. Last year's appropriations bill provided $400 million, largely due to the perseverance of my friend and partner in this effort, Congresswoman Nita Lowey from--she's my Congresswoman in New York, and a long-time champion of international education. And we have a $15 million pilot project to abolish school fees in one country in Africa.

So $400 million is a start, but it is far short of the U.S. share needed to cover the global financing gap in education.

To put it in context, $400 million, which is what we've appropriated for the entire world, is the financing gap that Pakistan faces for a single year. So I will continue to argue for increased funding and to emphasize the importance of funding international education as a U.S. priority and as part of an international global strategy.

So we have a lot of work to do, but I'm delighted that we have this U.N. task force, and that we have a partnership among so many of us as we try to think of ways,

11 both in the United States through the U.N., through the G8, and most importantly in the countries that are most affected.

So I'm pleased that we would have this important conference at a critical moment to take stock of where we are. We may be missing the mark in terms of meeting the 2005 gender equity goal, but we have a lot of energy behind this issue, and we need specific strategies around education and health care in order to be able to try to meet the mark in the years to come. Thank you very much.

[Applause.]

MS. GUPTA : Senator Clinton has a little bit of time to take a few questions if you have any?

MR. GUTTIEREZ: My name is Luis Guttierez. And this is my question: I'm sure that you are aware that girls are not sent to school in some cases for religious reasons, and I was wondering if you have given any consideration to this, and if you think that there is anything that can be done politically?

SENATOR CLINTON : Did you hear his question that there are some instances where girls are not sent to school for religious reasons, and I am, of course, aware of that.

But I also believe that primary education can be successfully achieved and religious objections can be overcome. I've seen that happen. I've talked with many people who've been part of making it happen. And I would just make a couple of points.

If there is no universal primary education, it leaves a vacuum. And some of the ways that vacuum is filled is through religious leaders who, for all kinds of reasons, decide that in their areas girls will not be educated. But in Afghanistan, where I've just come from, over 40 percent of the people who participated in the election were women.

President Karzai and the government of Afghanistan has just appointed the first woman governor to one of the provinces. Schools have just mushroomed all over the country, and there was some religiously framed objections to girls attending school, but the overwhelming majority of people wanted their girls to go to school.

So it was local resistance to that effort to try to disrupt and undermine education for girls that really was successful in keeping the girls in school, and, although, you know, the school may literally be a blanket under a tree, the important point is that we are reestablishing for the future the very clear commitment to education in Afghanistan.

In a recent conversation with President Musharraf, I was struck again by his efforts to try to reinstitute some form of universal primary education.

Now will there be areas that are harder than other areas? Of course. But this is a long-term effort that will be successful by convincing people that it is in their interests-that, you know, maternal health improves when, you know, girls and women are educated.

So there's just a lot of argumentation, evidence, facts that can be made. So I don't think we should be in any way dissuaded.

And the final point I would make on that is that because of the failure of states and the international community to provide for education, religious education, particularly in the form of the maddrasses, has filled that vacuum. And if you're a poor family in, you know, northeastern Pakistan, and there's no primary education available, and someone comes to you and offers, you know, not only an education, but three meals a day and housing to your sons, you're going to take that. It's better than, you know, anything else that's been offered to you.

So part of what we tried to do in the 9/11 Implementation Act is to provide more resources to expand the opportunities for governments to provide education, to remove

12 this vacuum that is often filled by religious leaders and dogma and often extremism. So, yes.

MS. BOCHER: My name is Coleen Bocher, and I work for a grassroots advocacy group called RESULTS, Senator Clinton.

SENATOR CLINTON:

MS. BOCHER:

Oh, excellent. I know RESULTS.

Well, great. Thank you. I thank you so much for mentioning what Uganda has done to eliminate school fees. The pilot project is very exciting. What

Uganda has done is very exciting. And I wonder if you have any thoughts about what we can to push other countries to do the same thing.

of the way that international organizations deal with countries. You know, I was perhaps a little bit harsh, but not in my view unduly so, because the creation of school going fees was really an international imperative for a lot of countries.

And so anything we can do to change the way that the World Bank, IMF, other organizations deal with the debt needs and the development agendas of countries is important.

I met recently with the new Minister of Education in Kenya, and that government has abolished school fees, and they've made a tremendous commitment to doing so.

But to go back to the first gentleman's question, you know, they have pastoral nomadic populations that are Muslim, and they've got a really difficult problem getting primary education into those areas. But the Minister of Education told me that outside forces are paying to send mullahs into those areas to proselytize and education the boys.

So we either will try to help these local governments provide primary education, and we can do it on a number of arguments. We can do it on it's the right thing to do. It's smart for, you know, your national development, and it's also smart for the security of your country and others, because, of course, we remember Kenya and Tanzania were attacked by Al Qaeda with the bombing of their embassies. So there's a lot of arguments to be made, but I think the international community has to be really committed and state behind doing this. And if we do, I think that we'll see a difference and maybe by, you know, maybe within the next decade, we can, if not meet completely, certainly get closer to meeting the 2015 goals.

MS. GUPTA : Any other? Just one last one perhaps?

SENATOR CLINTON: Yeah.

MS. : I think I can project. I'm a native New Yorker. We've been to these fairly--

SENATOR CLINTON: We're projectors--

MS. WILLIAMS: So a question and a comment. I'm glad that you mentioned

Kenya Tanzania. My name is Aleta Williams, and I work with USAID in the Africa

Bureau as an education advisor, and I had the pleasure of working on the education for development and democracy initiative, which was the Clinton Administration's Africa education initiative. I'm currently working on Push [inaudible] Initiative. Sorry.

SENATOR CLINTON: Good.

MS. WILLIAMS: And one of the things that--one of the efforts that we really have been trying to promote is working more with the local communities. While we've been doing it, it's been part of our USAID programs for as long as we've had education programs, and I have a colleague here who's been doing a lot of the work in West Africa.

We have placed an emphasis on really trying to address some of the issues that you mentioned--trying to open up greater opportunities for girls whose only opportunities, if any, are to attend these Koranic schools. We're trying to incorporate and integrate more

13 secular subjects into the learning experience. And so we're delighted to find out that-well, we know that we have [inaudible] before, and we're thrilled that there will be additional resources we hope, additional resources, to continue that for [inaudible].

SENATOR CLINTON: Thank you. Well, we have a long way to go before we get--I have one co-sponsor.

[Laughter.]

SENATOR CLINTON: And so anything you can do to encourage people. You know, and sometimes, you know, my constituents in New York say to me well, why would we spend money doing this? I mean, what about our own schools? Well, you know, absolutely. I mean, don't get me started on our budget and our deficit and all the other problems that we are facing right now. But I think that this, to me, is a smart investment in our security future. If you don't care about girls and you don't care about kids and you don't really care what happens to them, you know, I'm sorry for you and I'm sorry that that's your attitude. But at least make the security argument because we need people to be educated. We need them to participate in their societies, and we need particularly young women to, you know, think about the better future they want for themselves and their children.

So I'm very hopeful that this is a cause that will get broad support across our country, and we may not make it this year, but if we keep creeping up in the regular appropriations, Aleta, we'll keep providing funding for the programs you're supporting at

USAID, and we'll be--you know, slowly but surely make progress. Thank you.

[Applause.]

MS. GUPTA : Thank you very, very much.

[Applause.]

MS. GUPTA : Thank you from all of us for your leadership, Senator Clinton, and your commitment to this issue.

OPENING REMARKS

MS. GUPTA : Our second keynote speaker this morning is Professor Jeffrey

Sachs, Director of the U.N. Millennium Project, and special advisor to Secretary General

Kofi Anan on the Millennium Development Goals.

He's also currently Director of the Earth Institute at Columbia University, and holds several other titles. He also has a long and distinguished career and has authored hundreds of books and scholarly articles. But most importantly, I think, he serves as an inspirational and eloquent speaker on the inequalities that characterize our world, and on our collective responsibility as citizens in the industrialized world to rectify those inequalities.

I have been privileged to work with him on the Millennium Project. I have learned a lot from him, and been inspired by his energy and commitment to bring about the social and economic changes that we all work towards. Ladies and gentlemen,

Professor Sachs.

[Applause.]

DR. SACHS: Geeta, thank you for really such a warm and lovely introduction, and thanks to all of you for being here for caring about this issue and understanding its importance in the world. I want to pay tribute to several people in the room and not in a perfunctory way, they've been working round the clock for years, of course, Senator

Clinton, we're extremely grateful for all her leadership. It's real. It's longstanding, and, you know, we're counting on her to get that legislation. I think we have to dedicate ourselves to helping her get that through.

14

And Nancy Birdsall, the Director of the Center for Global Development, of course, is our leader in this city for pushing this agenda and does a marvelous job, and is one of the three co-chairs of the task force on education and gender produced the marvelous report that you've picked up this morning and probably have read weeks before.

Also Geeta Rao Gupta as Director of ICRW and another co-chair of this task force is a great leader, and if I've been able to teach you something, you've taught me so much more so this has been a wonderful process. And Amina Ibrahim, the third of the co-chairs of this joint task force that produced these two wonderful reports. We're grateful to you and also for what you're doing to help Nigeria, a country which has roughly one in five of all sub Saharan Africans, and is in desperate need of help and change, and Amina is one of the leaders of that effort, not only in education, but in all of

Nigeria's economic and development challenges.

Also you've already heard the spectacular role that Ruth Levine and Caren

Grown, Chandrika Bahadur played in helping this pretty complicated process which took place all over the world over three years and connecting a vast number of constituencies and stakeholders together, and also we owe a tremendous amount to Gene Sperling.

And in person. I also want to thank Ed and Cheryl Scott for making all of this possible in so many ways because your vision and--there your are--your name was invoked, favorably--but Ed and Cheryl have, through establishing the Center for Global

Development have helped to not only keep these issues alive in Washington, but add a new flame that's burning here that we're counting on to carry the day; and to the other sponsors of the conference.

Thank you. All of this counts a lot, and we have a very big hill to climb I have to stress. That's the main message that I want to convey in a few minutes this morning.

Let me read something quickly which does grab me as being straightforward and right. It says today more than ever U.S. foreign policy toward the developing world plays a vital role in the global balance between conflict and peace. U.S. national security challenges are increasingly complex, and the role of development is recognized as pivotal. This is reflected in President Bush's national security of the United States issued on September 17, 2002, which, for the first time, elevated development as the third component of U.S. national security, alongside defense and diplomacy.

Good words. They are in the budget request this year for the International Affairs

Account, dubbed the 150 account. They don't mean anything actually in reality right now in terms of the actual budget that goes around those words. But the words are right.

And our task is to make those words mean something actually, 'cause this is a city filled with vaporous words, and the ground realities are really very different; the ground realities of the people that we're actually discussing here who live several thousand miles away; even the ground realities of literally what surrounds those words, 'cause literally on this same page those words, pivotal. Did I see pivotal? Yes, I did see pivotal. For the first time elevated development is the third component of security, alongside defense and diplomacy. So on the same page, the development assistance line is cut by $300 million, and the child survival line is cut by $300 million.

Now this is really what we're after. What we're after is getting some reality into our lives, into our discourse, into our discussions.

First, let me say that the issue that we're discussing girls education and gender equality, and I would add sexual and reproductive health services, are not incidental goals. They are not just Goal Three of the MDGs. Without them, there ain't the other

15 seven goals. These are absolutely central to how societies function. They're central to economic development. Women's choice and women's empowerment is vital to every aspect of economic development, and girls education we know is vital to the empowerment of women in the coming generation.

We are in a year of Beijing plus ten. More words. Much too little implementation and no follow through by this government of ours right now on goals that were worthy, well thought out, and internationally agreed.

And so the task that we're talking about is not a small matter. I feel sometimes I just live in orbit these days, and yesterday I was in Ethiopia, and today I'm happy to be here. But I'm carrying with me the images, of course, that I saw in the last couple of weeks in rural Kenya and rural Ethiopia. We walked into a clinic, and a child was in convulsive seizures. There was a tongue depressor, so he would not bite off his tongue. I don't know whether the child survived or not. He had cerebral malaria. That's because the drug that he took, sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine, does not work anymore, and we know that. And yet we don't fund the [inaudible] and in combination therapies that do work.

They cost all of a dollar. So maybe this child will have lost his life for lack of our dollar or maybe he will have a lifetime of disability, cognitive, physiological disability from having been in coma and seizures. So that's what I saw in one room.

And in the next room I saw two people lying on a bed, head to foot. One dying of

AIDS, and the other adult suffering from malaria. So the one dying of AIDS will leave behind an orphan, and orphans won't get education. Now the one dying of AIDS is dying of AIDS because he lacks the dollar a day that's needed to keep him alive. It's actually less than a dollar right now. It's about 30 cents with SIPLA [ph] drugs or other generic fixed-dose combinations. This sub district hospital I was at has just gotten its first load in, and so maybe that individual will be saved.

Then we went--that was in Kenya. Then we went to Ethiopia to a rural area in

Tigre Province. It's a very dry area. The last five years the short rains have failed. This is probably the result of the warming of the sea surface temperatures of the Indian Ocean, probably the result of anthropogenic climate change, something we also don't do anything about here. So it's not incidental when the rains, when you live in a sub humid or arid environment, those short rains, the Belg rains, in Ethiopian can be the difference of life and death.

So when we went to the clinic, the children were talking about are they in school and so forth. Well, the problem there is that 50 percent of the children in this village in

Kararo Tabia [ph] in Tigre Province are less than 60 percent of the norm of weight for height, and height for age, stunting, wasting is pervasive. These are hungry children because the rain fails and you lose weight. You're immune system is suppressed, and you die if an infection comes, perhaps a bout of malaria, which is epidemic in this particular area.

We went next door to a little hut where one of the mothers in the village lived and spoke with her, and she told us that she spends six hours a day--six hours --collecting water, just collecting water. What you did turning on the tap this morning, she spends six hours a day. She takes three two-hour trips to the water hole. The water is not safe. Of course, this is unprotected springs and trickles of water. The whole water table has fallen dramatically. One morning we went to the bank of the river--this is a called a perennial river, which means it's supposed to flow all year. And there's no water at all in this river.

And a group of men in the village were digging a hole in the middle of the river bed down about two and half, three meters to get to the water table, which is below the river

16 bed now so that they could pump some water, carry some water up to their shriveled crops.

Well, girls and boys don't go to school when they're collecting water, when their mothers are collecting water six hours a day.

These are not impossible problems to solve actually. I'd say our climate change added a twist of the knife that is a very harsh reality. It means that any aid we give should come under the column of compensation, probably not aid. But even with that, these are solvable problems.

A diesel generator can pump water and save a whole village of women spending their entire lives collecting unsafe drinking water, and if you manage the bore hole carefully and properly, with proper pumping and getting the recharge rates to be equal to the discharge rates, then you can sustainably manage water. The health improves dramatically. The mothers actually have something to do when the daughters can go to school because they're not spending their whole young lives as beasts of burden also to stay alive.

You can drip irrigate. This is a place that with a little bit of investment could actually grow some fruit trees. The one thing they have absolutely par excellence is sunshine year round. And so orange orchards you could see with your mind's eye, but it requires some drip irrigation, which is not very much money, but beyond the means of this little community.

Malaria it's a wonder what a five-year long lasting insecticide treated net can do.

About three million children will die this year in sub Saharan Africa. Three million because they don't have a long lasting insecticide treated net which costs five bucks, lasts five years. A dollar a net per year. Two children typically sleep under it. Fifty cents per child per year. We're going to lose millions of children this year.

So I'm trying to figure out what the heck is happening to us in this country. Why we can't talk about anything honest anymore and make connections between words on paper, high concepts, great speeches, national security strategies and these ridiculous budget numbers, which are just coming from a different planet. And everything is faked.

And everything is spin. And we just can't grapple with even the most basic arithmetic.

Why are we cutting the child survival budget right now? Why aren't we leading the effort to get malaria under control. It would cost about three dollars per person per year in the rich world. About $3 billion to shift over to effective anti-malarials, environmental control, long lasting insecticide bed nets, presumptive treatment for young children and for pregnant mothers--in other words, the state of the art. These communities are desperate for it. It's only the ignoramuses that say there's nothing that can be done. You can't move the money, bad governance. It's people that don't go to a village that don't have a clue as to what the ground realities are and how desperate people are to stay alive.

As the Prime Minister of Ethiopia said to me a couple days ago, we don't use bed nets to fight wars. I always say bed nets don't always end up Swiss bank accounts.

What are we thinking, ladies and gentlemen? Why can't we do something so simple?

I raise this because this is what keeps children in school--when they're healthy, when they're fed, when they're not collecting water for hours. It barely costs any money at all.

So I went through this budget just stunned, place after place--child survival, investing in the health of the world's population, addressing global issues, special concerns, stabilizing fragile states, and promoting transformational development. Budget cut $300 million, to less than one--do I have this right--yes, $1.2 billion for the

17 developing world. That's about 50 cents per person per year. That's not going to accomplish very much at all is it? Because we don't do the arithmetic at all. And why are the budgets being cut? I can't imagine.

Child survival and maternal health to address the primary causes of maternal and child mortality and improved health systems primarily in sub Saharan Africa. Great.

You read that. Great. $326 million. Divide by 650 million people. Okay. Fifty cents for that wonderful goal of addressing the primary causes of maternal and child mortality.

Is this for real? Only in Washington.

The list goes on and on. I like this one. A total of $24 million for key regional countries--Djibouti, Ethiopia, Kenya, Nigeria, and South Africa--to support economic growth, democratization, anti-crime, and anti-corruption activities. $24 million. Two hundred sixty million people. Use that ten cents wisely would be my advice, because you have to spread it out among economic growth, democratization, anti-crime, and anticorruption activities. policy.

Are we grown ups? I'm serious. This is basic arithmetic. This is not national

We're very confused in this country. We blame the poor for their problems. We don't understand the number of absolutely practical steps that communities are taking on their own if we only help them could actually succeed. Children can stay alive. Water can be safe. Children can be in school. School meals programs can be provided. The whole point of our report is practical, low-cost, specific, targeted, measurable. But it costs something. You know, it costs something, and we're happy with tens of billions of dollars when we want to do something. We just don't want to do this right now. We want to fake it through these titles of programs. These are not real programs, because every place I go, including the two places that I was last week, Kenya and Ethiopia, there's no money to do the things that need to be done. And then I always get a U.S. official calling me at the end of the meeting quietly to tell me, by the way, Professor

Sachs, our budget is being cut this year, not increased.

So that's why we're here with the first failed MDG in 2005, and on our way to seven other failures, because we're faking it. And we have to decide really whether we want to live in a world where we fake it or not. I think it's not a good idea actually.

It's really my advice, serious advice. I don't think it's a good idea because our spin doesn't work in Koraro, Ethiopia. Our spin doesn't work in Saorey [ph] Nyanza

Province, Kenya. Our spin actually doesn't work outside the Beltway. All of this is known, everything I'm saying is trivially obvious to everybody except Americans, who don't hear otherwise.

And now they're starting to hear because you're raising your voices. But we do have to decide in our generation do we want to tell the truth or do we want to have labels for programs. Do we want to announce that it's one of the three pillars? Can you imagine a building built with three pillars? One pillar, military, has a $500 billion base, and the other pillar, called development assistance, has a $15 billion base. That's a lopsided building. That one is going to come crashing down. Those are our pillars of national security. We're spending 30 times more on the military than we are on development.

And of that $15 billion, most of it is going to strategic states. Afghanistan alone is going to get more aid than all of sub Saharan Africa in development assistance this year in this budget.

So it's a choice. It's a choice whether we're honest, whether we do the arithmetic or not. It's as simple as that.

18

The whole point, and I'll wrap up, you know to do what really needs to be done, you don't need one more promise, one new commitment, one new program. It's all been said a thousand times before, including at what this Administration really likes the

Monterrey Consensus. The Monterrey Consensus says in paragraph 42 we urge all developed countries that have not done so to make concrete efforts towards 0.7 percent of

GNP, 0.7 percent of GNP, in official development assistance. We are at 0.15, and we don't see any concrete efforts underway whatsoever.

Now the good news is the rest of the world is not so completely living in this parallel universe as we are. They're living in the actual world. And Europe is mobilizing to do things. And that's heartening because it actually makes you think that there's human to human contact being made and people understand the challenge and what can be done. And most of Europe is about to announce this year 0.7 with a real timetable.

So Geeta asked us, and I'll stop here, for some concrete suggestions. Let me give them to you.

First, the United States should endorse the Millennium Development Goals.

Strange, they don't do it. A hundred ninety governments do it. One government says we endorse the international development goals in the Millennium Declaration. They don't even use the three words Millennium Development Goals in sequence. Come on. Let's join the world. Millennium Development Goals. Those are the internationally agreed goals. Let's tell the American people about it. Let's tell them how we signed up to it.

Let's explain what they are and why those words that I read at the beginning are real. Our security depends on getting this right.

Second, let's chose a World Bank President that knows something about development.

[Applause.]

The names that have been proposed are shocking and would be a disgrace. This is professional work. This is not a game. It's also life and death for hundreds of millions of people. This is not corporate affairs, this is not military policy. This is development. So let's find somebody in the world--it could be an American, maybe not--maybe the

Administration can't find anyone that knows about development in this country. If not, let's find somebody that knows about development because that's what the World Bank is about. This is a highly technical, knowledge-based position of extraordinary importance for the world, not a joke and not a game.

Third, let's commit to 0.7 with a timetable. We've already committed to it, but it's the biggest secret in this country. We signed the Monterrey Consensus. I urge you all to download it on the computer. Read paragraph 42. See what the United States, the

President in person signed on to in Monterrey in 2002. We urge all developed countries to make concrete efforts towards the target 0.7 percent of gross national product in official development assistance.

We are $65 billion a year short. It's not a lot of money by definition because it's about a half a percent of GNP, which means that it's 50 cents roughly on the hundred dollars of our income. Right now, we're giving Africa about two cents out of every hundred dollars. That's it. That's the game we're playing. So why don't we commit like the rest of the world.

Let's help Senator Clinton pass the Education for All Act. That's a good campaign for us this year. That's real. That would finance what we're here to finance.

Finally, let's understand how much can be accomplished in a short period of time and let's try to connect to the rest of the world because others get it. We're the last to get it.

19

School fees could be dropped this year. All that is required is helping the countries make up the financing difference. That's the key. You see they use the fees to pay the schools. So if we actually helped to finance it, then you drop the fees immediately. When that's done, the children go to school. It's very simple. So this is a financing issue. This should be done this year. These school fees are a tragedy.

School meals for all children in schools. This could be done within the next year or two.

Malaria control with insecticide treated nets and proper medications. And while we're at it, why don't we save the 500,000 women who will die in childbirth this year for lack of basic obstetrical care. Something that also can be readily provided and is one of the great tragedies and shames of the planet.

Ladies and gentlemen, the only choice we have is whether we're living in the real world or the world of spin, and I hope we chose reality. Thanks very much.

[Applause.]

MS. GUPTA : On behalf of all of us, thank you very much, Jeff. Thanks for your comments and for your inspiring words. I would now like to welcome Nancy Birdsall,

President of the Center for Global Development, to the podium to introduce our next keynote speaker.

OPENING REMARKS

MS. BIRDSALL: Thank you very much, Geeta, and thank you to Jeff as well.

It's really a great privilege and a pleasure for me to introduce to you Senator

Chuck Hagel. In November 2001, Senator Hagel spoke at the launch of the Center for

Global Development. So he holds a very special place in my heart and in the hearts of my colleagues at the Center.

That was just two months, of course, after the September 11th tragedy, and what was heartening and remarkable to me when Senator Hagel spoke at our launch was how eloquent he was, how compelling he was, how he represented the heartland in speaking to the reality that it makes such a big difference what is America's role in the world.

Because it was right after September 11th, of course, he emphasized the security issues that Jeff referred to; that Senator Clinton referred to. What was also really wonderful was the way in which he represented the American people, including of the heartland, far away from what Jeff called the vaporous talk in Washington.

We have in Senator Hagel a person who does get it about the need to make a connection between the rich world and the poor world, and that means a lot to all of us at the Center for Global Development and, of course, at the International Center for

Research on Women, because at the Center in particular we're very concerned with insuring that the policies of the U.S. and the rest of the rich world are more and more friendly to development.

The Senator, in his work on the Hill, bespeaks the notion of a wise, measured approach to foreign policy, and he has show his concern within the context of foreign policy with the development issues that are so central to that policy insofar as that policy now includes defense, diplomacy, and development.

He is a member of the Foreign Relations Committee, Banking Committee,

Intelligence Committee. He chairs the Subcommittee of the Foreign Relations

Committee on International Economic Policy, Exports, and Trade Promotion. We could be more pleased to have someone who represents that approach to where America stands in the world to speak to us today on this issue that so many people here clearly care so much about whether we are going to miss the mark on girls' education. Senator Hagel.

[Applause.]

20

SENATOR HAGEL: Thank you very much. Nancy, thank you. I am privileged to be with you this morning, and I want to thank you all for what you to do, continue to do. You have been on a long journey, and I think that journey will take us all to areas that will, in fact, shape and transform the world, and it is because of organizations like yours represented here today and efforts, personal efforts, real efforts, in just words, not vaporous efforts that will make the difference.

Senator Clinton I know was here this morning. She has been a champion on these issues and others, and I have been reminded I think 17 times since I walked in that she has a bill.

[Laughter.]

SENATOR HAGEL: I will take a very close look--

[Laughter.]

SENATOR HAGEL: At Senator Clinton's bill. Senator Clinton and I have a very good relationship. I admire her greatly for her commitment to these kinds of efforts, so I will look and if we can join on this, we will. Whether I am a co-sponsor of that bill or not, I think Senator Clinton and I work rather well together on the overall issues, but I look forward to taking a long look at this bill.

I was going to bring my 14-year-old daughter this morning with some of her friends from her school, but in the interest of education, educating girls--since they have been out of school for almost a week because of snow and inclement weather, my daughter's mother thought it would be a better placed priority for her to stay in school this morning and having nothing to do with minimizing efforts or the importance of your organization. But I think they have been out of school since Wednesday of last week.

She was quite disappointed obviously for the content that she would miss this morning, having nothing to do with the fact that she would be out school again for another day.

But nonetheless, she is interested as are her friends.

There is no one in this room--I suspect no one in this country and probably around the world--that does not understand the importance of education. Education is the essence of human progress. Education is the foundation for empowerment. And we have a long way to go, especially in educating women--girls around the world.

There is progress. We have made some progress. We are not even near the edge of where we need to go on this issue. I think of Nancy's introduction of me and her comments about the heartland, which I appreciate. My constituents would appreciate that. I think when you talk of the heartland, of the work that the University of Nebraska at Omaha has been doing for many, many years in Afghanistan and continues to do.

Those are model programs that I have used to entice some of my colleagues to become more engaged, and those of you who are not familiar with what the University of

Nebraska at Omaha has been doing in Afghanistan, we have been there for a long time and helping educate, helping train teachers. We have an Afghan teacher program, and we have brought over the last three years to Nebraska over 200 Afghani women to help prepare them and educate them so that they can go back and teach. We have a program that brings young Afghani women into Nebraska to help educate them. Now we need to obviously get below that age group and that is much I understand the focus of your program today.

Listening a little bit as I got here a little later to what Jeff was saying, and his comments of what I heard are exactly on point as far as I'm concerned. And part I think of what Jeff was saying it's something that I have been talking about for a long time is that you cannot separate these great disciplines and great efforts in this arc of interests.

These are intersecting circles of interest that connect education, economic development,

21 stability, security, the environment. All fit within this great arc. And we struggle here in

Washington for many reasons every day, but we struggle in many ways principally because we are not integrating these interests of policy. We make policy far too often, even in today's more enlightened world we think, based on an isolated vacuum tube of interests. We do environment over here. We do some energy over here. We do economic development and trade back here, and have a little foreign policy over here, and we consider foreign policy some kind of a nebulous Kissingeresque kind of pursuit.

Well, foreign policy is the framework for all of our interests, for the world's interests, and here we are in a world of six and half billion people, interconnected, global in every way, and we're not going to unwind that. Whether it's a health issue, an education issue, a climate change issue, trade, transportation, telecommunications, we are in this together; and there are no boundaries. Certainly, we don't need to look much beyond what happened in this country on September 11th of 2001 to understand that security is no longer a matter of vast oceans on the east and west coasts, strong secure border on the north, and a good border on the south. It doesn't work that way anymore, and if no other lesson we should have learned from that tragic, tragic day in America and for the world, we should have learned that lesson; that the integration of all these policies is absolutely critical.

You take that deeper in what you're talking about, what you're doing, what you're leading on, education for girls, is what that is about--yes, individual enhancement, empowerment. Education does what we all know it does and why it's important. But it does something else. It stabilizes and secures a base of community, a base of interest, and it connects that interest that education, and it helps developing countries break that cycle of despair, of hopelessness. It deals with endemic health problems in poverty, in hunger. We will never ever begin to address these great challenges of the 21st century without education as the base.

We have taken a large segment of our society out of that in many regions of the world--women. And that cannot be. You know I occasionally remind some of my colleagues when they are talking about Jeffersonian democracy and America as the role model, and I say well, that's true but just remember that in America a hundred years ago, half of the citizens in America could not vote. Women could not vote a hundred years ago in the United States of America. So we had to work our way along here over a long period of time to empower all of our people.

Certainly the civil rights acts of the mid '60s were very much focused on that. So this country has been through a certain amount of that--different situations, dynamic times, pressures--and we're still not where we need to be in this country. But we should harness our resources and our leadership and our focus and everything that's good about our system and our society, and there is much good about it--imperfect absolutely--and harness that and project that in a way that really does affect the outcomes in the world.

Armies and divisions of soldiers will not change that. We will not impose our will, our form of government, or any other dynamic of our society with armies. The military component is a very critical component. It is a guarantor of foreign policy. We understand security. We understand that. But that alone won't change things. It will not affect the outcome. It will be people. It will be education. It will be empowering all the peoples of the world.

So for what you do, I not only as a United States Senator am grateful, but as a parent of two young people, I am grateful, because it will be you who really reshape the world. It will be you who will lead the transformation of mankind. And we are living at such a time I believe. I believe we are living at a very defining time in the history of

22 man. And these times come every 50 years or so--40, 45, 50, 60 years. They do come in cycles, and we are in such a cycle. How long that lasts I'm not near wise enough to know.

So with that and for all those reasons, I'm grateful that you would give me the privilege of exchanging some thoughts and before I go back and vote here on a couple of things that I think they're going to call the vote shortly, and prepare myself to meet

Senator Clinton on the floor of the Senate on her bill, I would be very happy to respond to any questions, comments, thoughts, advice, wise counsel. Gene Sperling has already given me some. He's already coming to see me soon.

MS. : I'm just here to help you with questions.

SENATOR HAGEL : All right. Well, good. That means you answer. Yes.

Yes, sir.

MR. GUTTIEREZ: My name is Luis Guttierez. And I was wondering if 9/11 didn't do it, and if hitting $50 per barrel of oil didn't do it, do you have any idea of what kind of a crisis will be necessary to bring the American people to the level of awareness that is necessary to make it politically feasible to embrace the Millennium Development

Goals?

SENATOR HAGEL: The Millennium--which goals?

MR. GUTTIEREZ: The Millennium Development Goals.

SENATOR HAGEL: Oh, are you speaking partly specifically about the

Millennium Challenge Accounts? Is that what you're--

MR. GUTTIEREZ: I'm speaking in general about Professor Sach's proposition--

SENATOR HAGEL: Okay. I see what you mean--

MR. GUTTIEREZ: That the United States--

SENATOR HAGEL : Yes. I understand.

MR. GUTTIEREZ : Has to become active in--

SENATOR HAGEL: Yes. I got it. I understand. Thank you. Well, I support what Professor Sachs was saying, and I support those goals and I think reflected in the comments I've just made I think you at least get some sense from me what I think the priorities need to be for our policy and our government and our leadership and resources in the world, which would I think fit pretty closely with what Jeff talked about. And I think the forces of reality are bringing this into a clear focus for the American people.

You mentioned two specific examples. You mentioned September 11th and $50 a barrel oil, and it's probably going to get to $60 a barrel oil. And there will be other pressures that will focus on this, what I call the forces of reality that will make it clearer and clearer to the American people this wide angle lens understanding and approach to these great challenges of mankind, and it is not enough to just be worried about American homeland security and securing our borders. That's part of it, of course--of course. But it has to go much wider than that.

I have spoken out in concern and in the Congress last three years and fought for a recommitment to exchange programs. Our immigration laws need to be reformed. I think it's nuts what we're doing in Cuba. I think it's crazy what we're doing to ourselves on a lot of the immigration issues. We have an immigration system that doesn't work.

We're pushing people out of this country that want to be here. I mean, after all, who is

America? America is a quilt and is a quilt that reflects colors, races, religions, ethnicity-all the great strengths that were brought to this country over the last 300 years from all over the world. That's who America is. And we need strong appeals outside. And we need new vitality to come to the United States, not just for economic reasons, but other reasons.

23

And so it is coming I think into clearer focus and vision the realities that connect

America to the rest of the world--exchange programs--all the programs that you're involved in--us, the United States willing to lead and do things that connect us to the rest of the world and the perception--and changing the optics.

Since World War II, we have been the leading power in the world. And the optics that we have viewed the world from have been essentially American optics. We view the world from our optics. We're going to have to reverse some of that. And we're going to have to understand how the rest of the world sees us, and why. That doesn't mean you give up your values, your expectations, and who you are, your sovereignty. That's nonsense. But the fact is this is going to have to be a different kind of a world because the world, if for no other reason, is just far too dangerous today than it's ever been if we don't do that.

MS. BIRDSALL: I'm going to ask you a question, if I may.

SENATOR HAGEL: Yes.

MS. BIRDSALL: It's a little unfair, but you mentioned the Millennium

Challenge Account of President Bush, which is an excellent initiative for ensuring that very poor countries with good governments get substantial resources to move ahead.

There are four or five countries eligible for the Millennium Challenge Account that are also eligible for a worldwide program agreed amongst all the donors, including the U.S., for something called the Fast Track Initiative for Education. Maybe I could ask you it's in the form of--it's a quasi question. Is there something that you can do or we can do to press forward on at least ensuring that Millennium Challenge Account funds, which are available and could be spent quickly, are allocated if the countries want to this initiative on education?

SENATOR HAGEL: Well, I think the general answer to that is first of all, yes, that we could do that. Another part of that question is what can I do, what can you do, what can this group do. I think inform and educate representatives on Capitol Hill,

Congressmen and Senators, about why this is important, why it can be done.

One of the reasons that I have been a strong proponent and a leader on the

Millennium Challenge Accounts is it gives these countries eligible, and it I think it is smart to focus the way we have the flexibility, Nancy, to be able to address their own problems' unique foundational issues. Every country is different. We understand that and you can't compartmentalize and make rules for every country. And the same way, there are certain general standards and certainly of accountability. That's what the

Millennium Challenge Account is about. But let those countries decide where their priorities are. I am a strong proponent of that; will continue to be. The specific program that you mentioned needs to be integrated into that because even though these are more economic development kind of funds and programs, you can't again, I say, as I said earlier disconnect these circles of interest that connect. And education is as basic to that--

[START OF TAPE 2]

MR. BIRDSALL: The Civil Society Action Coalition on Education for All.

This is a coalition of 124 different civil society organizations working on education in

Nigeria. So it's really a pleasure--it has been a pleasure work with Amina. She is a person who has worked inside government and outside government to make a difference for the children of Nigeria, and she has become a spokeswoman at the global level on these issues.

Amina will introduce to you the panel. You have the floor, Amina.

FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE EDUCATION SECTOR FROM THE

U.N. MILLENNIUM PROJECT TASK FORCE

24

ON EDUCATION AND GENDER EQUALITY

MS. IBRAHIM : Thank you, Nancy. I'd like to add my voice of welcome to everybody for making the time to come and be with us today. It is an important opportunity to engage with the work of our task force over the last two and a half years, and to hear some of your feedback on such important issues.

It also comes at a time when we look at the first target, as Geeta has said, and why we say missing the mark. In my country, for instance, we've missed in half the country, but the other half we still have a chance to reach it, and that's what we want to look at-the specific and strategic ways to achieving that within the next decade or sooner.

The panel this morning is going to deal more specifically around the issues of the country-level challenges by national governments and societies and also the donor community.

I have with me today four panelists, who've got vaster experience and would say in the field in their different aspects. I'd like to first start by introducing Vicky Colbert de

Arboleda, from Colombia. She is the founder and executive director of the Back to

People Foundation in Colombia, and she will be speaking to us about the country experiences from Colombia.

I then have my friend and colleague, Desmond Bermingham, from the

Department for International Development in the U.K. And Desmond is the head of the

Education Office and chief advisor to the Policy Division in the U.K. He will be giving us a perspective on the donor challenges, which are numerous. So from the U.K. side, and this is a year that we see the U.K. doing a lot in the forefront of championing the cause for our development issues.

Elizabeth King--sorry--Beth King. All right. It's Elizabeth. Beth King, a lead economist in the Development Research Group of the World Bank, will also be giving us a perspective on what helps make the donor relationships work.

And last but not least our director from the Education for Global Monitoring

Report, Nicholas Burnett, Nick Burnett, of UNESCO. He's been in charge of an independent report which monitors and tasks us on how far, in fact, we've gone to achieving EFA, the Education for All goals within the education sector.