Using Escaped Prescribed Fire Reviews to Improve Organizational Learning Final Report

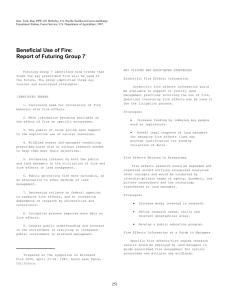

advertisement