Lecture 12 and 13: Macro dynamics of the open economy:

advertisement

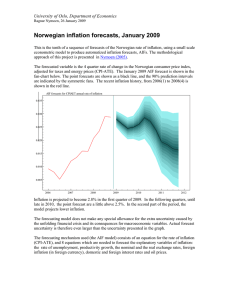

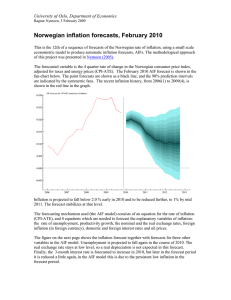

Inflation targeting in the AD-AS model The different regimes explained in Lecture10: Lecture 12 and 13: Macro dynamics of the open economy: Current monetary policy of small open economies Foreign exchange rate market exogenous variable Foreign exchange reserves Exchange rate Money market Money supply exogenous Interest rate variable None I III V II IV VI In Lecture 11 we analyzed R-I, a so called money targeting regime, and compared it to the R-VI (Et is targeted) Ragnar Nymoen In R-I the instrument of monetary policy is market operations: buying and selling of domestic bonds controls the supply of money in the domestic money market. November 13, 2007 2 1 Why consider alternatives to R-I? Recall the “supply of money function” of the open economy: ∆Mt = −∆Bt + Et · ∆Fg,t + ∆Et · Fg,t In R-I ∆Fg,t = 0 and Fg,t = F̄g . Revaluations of the stock of foreign currency F̄g affects ∆Mt somewhat, but according to the theory of R-I, such movements are countered by market operations (∆Bt). Changes in the net supply of bonds can also be used to increase or lower Mt independently of the market for foreign exchange. Hence, monetary policy independence in R-I: the interest rate is determined on the domestic money market. No such independence in R-VI, because the interest rate is determined in the market for foreign exchange. Remember that the discussion of R-I and R-IV was based on the assumption of perfect capital mobility (as in the IAM book). A full discussion is beyond this course, but in practice R-I failed to live up to the expectations founded in the theory just summarized: It turned out to be difficult to control money supply. Two issues in particular seem to have been important: a) Which money stock measure to target (M1, M2 or M3) b) In practice central banks rode two horses: tried also to intervene in FEX market (dirty float), which affect money supply In any case, R-I was really never considered an alternative when several SOEs started floating their exchange rates in the 1990’s. The alternative most countries settled for is called inflation targeting. In our typology inflation targeting can be seen as an extension of R-III. The interest rate is the used as an instrument to achieve a certain inflation rate (the target). Therefor it is “exogenous in the domestic money market”. However it it is endogenous in the wider setting of our macroeconomic model. We now define the inflation targeting regime 3 4 Inflation targeting defined We make a short-cut and replace equation (2), page 769 in IAM with the following policy response (equivalent to what IAM also eventually ends up with) f it = it + h(πt − π ∗) h > 0. (Policy response) where π ∗ denotes the inflation target, usually number like 2% or 2.5% (annual rate). f We follow IAM and make the following simplifying assumption π ∗ = π̄ f , target set to the constant foreign inflation From policy response function and expectations: f it = it + h(πt − π̄ f ) which is eq (14) on page 776. We can now augment the AD-AS model with this ’policy rule’. Note: could have coefficient different form 1 in front of it as well. Remark to table 25.1: Norges Bank does not acknowledge that it operates with “tolerance bands”. Rather a horizon (1-2 years) over which the target should be achieved. 6 5 The short-run analysis (inflation targeting) f yt = β0 + β1ert − β2rt + β3gt + β4yt e rt = it − πt+1 f ert = ∆et + πt − πt + ert−1 πt = πte + γ(yt − ȳ) + st f it = it + ee + αe(∆et + et−1) αe < 0 f it = it + h(πt − π̄ f ) mt − pt = m0 − m1it + m2yt, mi > 0, i = 1, 2 (1) (2) (3) ∆et = 1 f (it − it − ee) − et−1 αe (4) substitution of it from (5) (5) (6) −1 f 1 f (it + ee) − et−1 + e (it + h(πt − π̄ f )) e α α 1 = e (h(πt − π̄ f ) − ee) − et−1 α We therefore obtain the short-run AD schedule from ½ ¾ 1 f f ) − ee) − e r yt = β0 + β1 (h(π − π̄ + π − π + e t t t−1 t−1 t αe n o f f f e − β2 it + h(πt − π̄ ) − πt+1 + β3gt + β4yt Note that (4), is a generalization of eq (9) on page 771. IAM omits ee and et−1, and αe corresponds to −θ in IAM. Skip the discussion on p 772 and 774, it represents an internal inconsistency (non zero risk-premium and dirty float even though perfect capital mobility here). Compared to R-I we have one more equation. Hence mt is endogenous in the short-run model of inflation targeting 7 From (4): ∆et = 8 (7) (8) We adopt IAM’s assumptions about inflation expectations: e πt+1 = πte = π ∗ = π̄ f hence the model becomes ½ ¾ 1 f f ) − ee) − e r yt = β0 + β1 (h(π − π̄ + π − π + e t t t−1 t−1 t αe n o f f f f − β2 it + h(πt − π̄ ) − π̄ + β3gt + β4yt (9) − and πt = π̄ f + γ(yt − ȳ) + st (10) Differentiate (9) to obtain the slope of the R-III short-run AD-curve: ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ∂πt ¯¯ ∂πt ¯¯ − >− , when αe < 0 ¯ ¯ ∂yt ¯AD,rV I ∂yt ¯AD,rIII ∂πt ¯¯ ∂πt ¯¯ >− , when αe < 0 ¯ ¯ ∂yt ¯AD,rV I ∂yt ¯AD,rIII hence the short-run AD schedule is flatter in R-III (inflation targeting) than in R-VI. ¯ ∂πt ¯¯ −1 = <0 ¯ β1 ¯ ∂yt AD,rIII β1 + h(β2 − α e) consistent with β̂1in eq. (15) on page 776 in IAM. 10 9 Interpretation of slope-difference inflation The interpretation of the difference has to do with how the interest rate is determined in the two regimes: When πt increases, y-demand is reduced in both regimes through the real exchange rate, er . But there are additional effects in R-III: The interest rate is increased (monetary policy response) which leads to further reduction in yt. f R-III Hence regime III is different from the fixed exchange rate VI, but also from the floating exchange rate regime I (money as the target) where lower demand for money reduces the interest rate in the domestic money market. R-VI R-I y y We have generalized figure 25.3: AD(flex) represent only one sub-category of floating exchange rate regimes. 11 12 Short-run effect of a supply-shock Long-run effects of a supply-shock Consider a positive aggregate supply shock in period t = 1, s1 < 0 (s0 = 0) The impact multipliers: If the reduction in s is temporary: no long run effects. π − π̄ f = 0 from AS (the Phillips curve). Then er = er0 from definition of real-exchange rate. If a permanent reduction of s, then apparently π − π̄ f = s1 < 0 which cannot be reconciled with GDP: largest for R-III, smallest for R-I. Inflation: Largest reduction for R-I, smallest reduction for R-III. e πt+1 = πte = π ∗ = π̄ f The fixed exchange rate regime (R-VI) is an intermediate case. Paradox is resolved by nothing that ȳ is increased by the permanent positive supply shock. The natural rate of unemployment is lowered. So π − π̄ f in the long-run as before. But for higher ȳ. If h → ∞ R-III multipliers approach R-VI multipliers (not R-I). 14 13 Short-run effects of a demand shock However, note that for a given π: ¯ dyt ¯¯ = β3 ¯ dgt ¯πt=π̄,rIII Use fiscal policy again to represent a demand shock. We already know that R-I and R-VI can be compared by (identical) vertical shifts of the AD curve: However, from (9) ¯ ¯ dπt ¯¯ dπt ¯¯ β = = 3>0 ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ dgt yt=ȳ,rI dgt yt=ȳ,rV I β1 ½ 1 f yt = β0 + β1 (h(πt − π̄ f ) − ee) − et−1 + πt − πt + ert−1 e α n o f f − β2 it + h(πt − π̄ f ) − π̄ f + β3gt + β4yt we see that ¾ ¯ dπt ¯¯ β3 = ¯ β1 ¯ dgt yt=ȳ,rIII β1 + h(β2 − α e) so (unless the trivial case of h = 0) a vertical shift are not comparable (IAM p 782) 15 since there are no indirect demand side effects of a change in y in this regime (yt is not included in the policy response function). The same is true in R-VI where the interest rate is determined on the FEX marked. Hence, from n f yt = β0 + β1 πt − πt + ert−1 n f o o f e − β2 it + ee + αe(∆et + et−1) − πt+1 + β3gt + β4yt we have ¯ dπt ¯¯ = β3 ¯ dgt ¯πt=π̄,rV I hence, we can make a comparison of regime III and VI with the aid of a horizontal shift of the AD schedule. See IAM p 782 for the algebraic analysis. 16 The impact multipliers (of a change in gt): GDP: larger for R-VI than for R-III. Inflation: larger for R-VI than for R-III. Hence there is no clear cut answer to which monetary policy regime give most automatic stabilization to shocks. Relative frequency of demand and supply shocks is one aspect. This theme is developed further in IAM ch 26.1-26.2, in different directions, which we leave for self-study. 17 Choosing the rate of inflation Sometimes one the message is communicated that inflation targeting is not only about stabilization, but also about “choosing a different rate of inflation than the foreign rate”. In the model, such a policy choice entails keeping π ∗ as a policy determined parameter in the interest rate response function. The steady-state consistent with π = π ∗ and a constant real exchange rate, now implies that ∆e = (π ∗ − π f ), so (π ∗ − π f ) > 0 in the steady-state implies a constant rate of nominal depreciation. 18 Operational inflation targeting (Case of Norway) Characteristics of the regime 1. A floating exchange rate regime 2. The target of monetary policy is low and stable inflation 3. The operational target is the forecasted rate of inflation (1, 2 or 3 years ahead) 4. The instrument is the interest rate that the Central Bank sets as the loan rate in the domestic short-term money market. The interest rates offered to the public are higher but they are highly correlated with the CB’s sight deposit rate (’foliorente’). (a) Signaling, and building up of credibility: By acting on the macroeconomic prospects (in practice the CB’s own forecasts) rather than observed realities, monetary authority can signal a commitment to the target of low and stable inflation. The CB hopes that this will influence inflation anticipations among households and firms, which will in turn make goal achievement easier (b) The transmission mechanism is dynamic: it takes time before a change in the instrument affects the rate of inflation. Hence by acting “now” the costs of achieving the target is less than by waiting until a too high/low inflation rate becomes a reality. 6. Inflation targeting is flexible when the target horizon is long, so that interest rate adjustments can be gradual. 5. The CB’s interest rate setting is forward looking. There are two reasons given 19 20 A premise is of course the interest rate has an effect on the rate of inflation. What does the evidence say? Consider the Norwegian Aggregate Model for example. Figure 1: The transmission mechanisms in Norwegian Aggregate Model 21 The implications from this set of multipliers are: 1. The interest rate affects inflation through a complicated causal chain, confirming Figure 1. 2. Small and temporary interest rate changes will work no wonders for the rate of inflation 3. The most lasting, and over time strongest, influence is through demand. 22 Inflation forecasting and targeting Inflation targeting: the operational target variable is the forecasted rate of inflation, π̂T +H|T . Interest rate set so that it bring the forecasted inflation rate in line with target, π∗ Flexibility: related to the length of the forecasting horizon, H (as well as of other aspects of the “utility function”). 4. Flip of the coin of 3. is that i adjustments are best suited to offset demand shocks. Large supply shocks represent a challenge. However, a inflation forecast is uncertain, and might induce wrong use of policy. Hence, a broad set of issues related to inflation forecasting is of interest for those concerned with the operation and assessment of monetary policy. 23 24 A favourable situation occurs when it can be asserted that the bank’s forecasting model is a reasonably correct representation of the true inflation process of the economy. In this case, forecast uncertainty can be represented by conventional forecast confidence intervals, or by the fan-charts preferred by best practice inflation targeters. However an assumption of model correctness is not a practical basis for economic forecasting, as proven by the high incidence of forecasts failures. A characteristic of a forecast failure is that forecast errors turn out to be larger, and more systematic, than what is allowed if the model is correct in the first place. In other words, realizations which the forecasts depict as highly unlikely (e.g., outside the confidence interval computed from the uncertainties due to parameter estimation and lack of fit) have a tendency to materialize too frequently. 25 Situation B represents the situation most econometric textbooks conjures up, The properties of situation A will still hold–even though the inherent uncertainty will increase. The theory of inflation targeting also seems stuck with B. As stated: forecast properties are closely linked to the assumptions we make about the forecasting situation. One possible classification, is: A The forecast model coincides with actual inflation in the econometric sense. The parameters of the model are known and true constants over the forecasting period. B As under A, but the parameters have to be estimated. C As under B, but we cannot expect the parameters to remain constant over the forecasting period–structural changes are likely to occur somewhere in the .system. D We do not know how well the forecasting model corresponds to the inflation mechanism in the forecast period. A is a very idealized description of the assumptions of macroeconomic forecasting. Nevertheless, there is still the incumbency of inherent uncertainty–even under A. 26 A forecast failure effectively invalidates any claim about a “correct” forecasting mechanism (Situation A or B). Upon finding a forecast failure, the issue is whether the misspecification was detectable or not, at the time of preparing the forecast. In real life we of course do not know what kind of shocks that will hit the economy, or the policy makers during, the forecasting period, which is the focus of situation C. Structural breaks and regime changes are the most important source of forecast failure. Given that regime shifts occur frequently in economics, and since there is no way of anticipating them, it is unavoidable that after forecast structural breaks damage forecasts from time to time. The task is then to be able to detect the nature of the regime shift as quickly as possible. Situation D finally leads us to a realistic situation, namely one of uncertainty and professional discord regarding what kind of model best representing reality. This opens up the whole field of model building as well as the controversies regarding econometric specification, so we will leave that subject here. Hence in there is a premium on adaptation in the forecasting process, in order to avoid sequences of forecast failure. 27 28 Lack of adaptation will make the forecast susceptible also to before forecast structural break leading to unnecessary forecast failure. As an illustration, suppose that the following reduced form model—derived from a structural model (AD-AS for example)– is used for forecasting Relevance for inflation targeting? πt = δ + απt−1 + β1it + β2it−1 + εt, t = 1, 2, 3..., T, Forecast quality per se becomes of interest in this policy regime. −1 < α < 1, β1 + β2 < 0, The rate of inflation, being a nominal growth rate, is particularly susceptible to forecast failure (shifts in means of nominal variables in particular are notorious). If central bank’s do as they claim, and set interest rates to affect the inflation forecast, then regime shifts will not only damage the inflation forecasts, but will also interest rate setting. But in which way (with what consequences) depends on the operational aspects of inflation targeting. 29 iT |T = 0 where μ denotes the long run mean of inflation. Note: This a the so called interest rate path in simplified form 31 πt is the rate of inflation, and it is the interest rate. Suppose, for simplicity, that the central bank have chosen a 2 period horizon. The forecasts are prepared conditional on period T information, so π̂T +1|T = δ + απT + β1iT +1|T + β2iT |T (12) 2 π̂T +2|T = δ(1 + α) + α πT + αβ1iT +1|T + αβ2iT |T + β1iT +2|T + β2iT +1|T (13) There are 2 degrees of freedom if the bank chooses to attain the target π ∗ in period 2 (inflation targeting is flexible), and iT +1|T and/or iT |T can be set to (help) attain other priorities. 30 For simplicity, set iT +1|T and iT |T to some autonomous level, represented by 0 (hence let it be a deviation from its mean, the period 1 interest rate is equal to the mean interest rate). Hence, the interest rate path in this case is iT +1|T = 0 o 1 n −μ + α2(μ − πT ) + π ∗ iT +2|T = β1 (11) (14) In a constant parameter world, this path will secure that πT +2|T is equal to π ∗ on average. But if μ increases in period T + 1 and T + 2, a regime shift, both π̂T +1|T and π̂T +2|T will be too low, possibly representing a forecast failure. However, only iT +2|T is affected by the forecast failure, and can replaced by iT +2|T +1 in the next forecast round. The announced interest rate path is subject to the regime shift. Not today’s interest rate. With a different operational procedure, designed to move π̂T +1|T “in the direction” of the target, iT |T may be contaminated by regime shifts in the transmission mechanism. 32 The Norwegian Central Bank, in particular, has announced that interest rate changes, will as a rule be gradual. We can model this by setting: iT +j−1|T = γiT +j|T , j = 1, 2, ...H, 0 ≤ γ < 1 Norges Bank’s inflation forecasts Inflation forecasts are published in the bank’s inflation reports, IRs. which gives o γ2 n iT |T = −μ + α2(μ − πT ) + π ∗ Bn o γ iT +1|T = −μ + α2(μ − πT ) + π ∗ (15) B n o 1 iT +2|T = −μ + α2(μ − πT ) + π ∗ B where B < 0 is function of α, β1, β2 and γ. With gradual interest rate adjustment, regime-shifts and forecast failures are more serious, since interest rates today are affected, not only the i-path. 33 A main feature of BM is that the joint contribution of all interest rate channels secures a sufficiently strong and quick transmission of interest rate changes on to inflation to justify a 2 year policy horizon. This view of the transmission mechanism has left its mark on the published inflation forecasts, which typically revert to the target of 2.5% within a 2-year forecast horizon. But in the summer of 2004, this view was changed. 35 The details of the process leading up to the published forecast is unknown to the outsider, but the bank’s beliefs about the transmission mechanism between policy instrument and inflation, represents a main premise for the forecasts, and secures consistency in the communication of the forecasts from one round of forecasting to the next. For simplicity, we refer to the systematized set of beliefs about the transmission mechanism as the Bank Model–BM for short. 34 There is a trade-off between the wish to provide useful forecast, and the wish to avoid forecast failure. Forecasts with high information content come with narrow uncertainty bands. Conversely, the wider the uncertainty bands are, the less information about future outcome is communicated by the forecast. A simple indication of the information content of the inflation forecast is therefore to compare the width of the uncertainty bands with the variability of inflation itself (measured by the standard deviation over, say the last 5 or 10 years). If the forecast confidence region is narrow compared to the historical variability, the central bank forecasts can be said to have a high intended information value, see figure 3. 36 0.030 0.025 1. Norges Banks believes in low forecast uncertainty. High information content in forecast for the first couple of quarters. Inflation 0.020 0.015 IR 1/02 IR 1/04 2. Maximum uncertainty is reached fast- Hence Norges Bank acknowledges that there is a strict limit to the predictability of inflation? IR 1/05 IR 1/03 0.010 0.005 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 3. Forecast uncertainty is increased in IR 1/04 and after. A sign of adaptation? 2008 Time Figure 3: Uncertainty measures of Norges Bank’s inflation forecasts in Inflation Reports 1/02, 1/03 and 1/04. The lines show the width of the the approximate 90% confidence region for the 12 month growth rate of CPI-ATE. 38 37 0.04 IR 1/02 IR 2/02 0.04 0.02 0.02 actual actual 0.00 0.00 2001 0.04 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 IR 3/02 2001 forecast 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 IR 1/03 0.04 0.02 forecast 0.02 In the IR 2/02 forecasts the first four inflation outcomes are covered by the forecast confidence interval, but the continued fall in inflation in 2003 constitutes a forecast failure. actual actual 0.00 0.00 2001 2002 IR 2/03 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 0.04 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2006 2007 2006 2007 IR 3/03 0.04 forecast forecast 0.02 0.02 actual Specifically, the forecast confidence interval of IR 3/03 doesn’t even cover the actual inflation in the first forecast period. actual 0.00 0.00 2001 0.04 6 of 8 graphs show clear evidence of forecast failure. forecast forecast 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 IR 1/04 2001 0.04 2002 actual 2005 forecast 0.02 0.00 0.00 2001 2004 actual forecast 0.02 2003 IR 2/04 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 The 7th panel shows that the forecasted zero rate of inflation for 2004(1) in IR 1/04 turned out to be accurate. The forecasts have been substantially revised from IR 3/04. Whether this will prove enough to end the sequence of poor forecasts, remains to be seen. Figure 4: Norges Bank’s inflation forecasts, 90% confidence regions and the actual rate of inflation. The next section contains an evaluation by way of presenting ex post forecasts based on information which were available to the forecasters at the time of preparing the IR forecasts. 39 40 How avoidable was the forecast failure? As pointed out, poor forecasts due to after forecast structural breaks are unavoidable in economics. Given that fact, there is a premium on having a robust and adaptable forecasting process. Allowing relevant historical shocks to be reflected in forecast uncertainty calculations contributes to robustness in the forecasts, avoid too narrow forecast confidence intervals. Yet, as any nominal variable, inflation may be subject to frequent changes in mean, exactly the type of shocks that will damage forecasts. Adaptable forecasting mechanisms have the ability to adjust the forecasts when a structural change is in the making, or at the latest, when a forecast failure has manifested itself. This may have some relevance for the recent forecasts, since the low and stable inflation rates of the late 1990s may have lead some forecasters to down-play uncertainty. 41 42 The forecast failures also give rise to the question whether the sequence of poor forecasts was avoidable at the time of preparing the forecasts. This is a complex issue which needs to be analyzed from several angles. Here we follow an on-looker’s approach, and set up a forecasting mechanism which features at least two elements which logically must be present in the forecasting process in the bank: 1. All explanatory variables of inflation are themselves forecasted. Hence, our ex-post forecasts do not condition on variables that could not have been known also to the forecasters at the time of preparing the different inflation reports. Note that in our ex post forecasts, the up-dating of the forecasts is automatized. In real life forecasting, the revision of the forecasts from one inflation report to the next is done by experts. In comparison, our econometric forecasts are naive. In general, naive econometric forecasts are not particularly adaptive, but are prone to failures themselves. The set of forecasting equations was estimated on a quarterly data set which starts in 1981(1). Figure 5 shows the sequence of model forecasts. 2. Just like in a practical forecasting situation, the forecasts are updated: model parameters are re-estimated as new periods are included in the historical sample, and, more importantly for the forecasts themselves, the initial conditions are changed as we move forward in time. 43 44 0.04 AIR 1/02 0.04 0.02 0.00 0.00 2001 0.04 2002 2003 2004 2005 AIR 3/02 2001 0.04 0.02 2003 2004 2005 2. Even though the second year forecasts in “IR 1/02” show too high inflation, there is in fact a forecasted weak tendency towards lower inflation in 2003. 0.00 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 AIR 2/03 2001 0.04 0.02 0.02 0.00 0.00 2001 0.04 2002 AIR 1/03 0.02 0.00 0.04 1. The confidence bands of the forecasts are wider in “IR 1/02”, both for the one and eight quarter ahead forecasts. AIR 2/02 0.02 2002 2003 2004 2005 AIR 1/04 0.02 2003 2004 2005 2002 2003 2004 2005 2002 2003 2004 2005 AIR 2/04 3. Since the second year actual inflation rates are within the corresponding confidence bars, these outcomes do not represent forecast failure in Figure 5, while they do in the Norges Bank forecast. 0.02 0.00 2001 2001 0.04 2002 AIR 3/03 0.00 2002 2003 2004 2005 2001 4. In the panel, labeled “IR 3/02”, the impact of conditioning on 2002(2) shows up in narrower confidence bands for 2003, which in fact almost makes the realized inflation rate in 2003(4) a forecast failure. Figure 5: Forecasts from an econometric model of inflation, where we have emulated the (real time) forecast situation of the Norges Bank inflation forecasts. . 5. The next three panels in Figure 5 show an even more market difference from the Norges Bank forecasts. 45 46 A subjective assessment In the period 2001-2005 official monetary policy in Norway may have been hampered by several problems and mistakes 5. Interest rate decisions might have suffered, but 1. Overestimation of the effect of the interest rate on inflation (the interim multipliers) by Norges Bank. 2. Underestimation of the period of adjustment and of the forecast uncertainty. Time will show if these are still only teething problems. 6. 2006 and 2007 have shown a more adaptive approach. Forecast accuracy improved in 2006, and so far in 2007. 3. Very slow identification of the nature of the drop in the rate of inflation that started in 2003 (relative weight on supply and demand factors, an on domestic and foreign). 4. Exceptionally slow adaptation of the forecasts. 47 48 Deviation INFJAE DEPR .2 PBGR 1 .0 0.5 0 0.0 -1 -0.5 -2 -1.0 -3 -1.5 -.2 -.4 -.6 -4 -.8 -2.0 -5 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 -2.5 2007 2008 YGR 2009 2010 2011 2012 2007 2008 0.2 0.2 .8 .6 0.0 0.0 -0.2 -0.2 -0.4 -0.4 -0.6 -0.6 -0.8 -0.8 2009 2010 2011 2012 2011 2012 UR2 WCINF .4 .2 -1.0 .0 -.2 -1.0 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2007 2008 2009 2010 Figure 2: Dynamic multipliers from a permanent increase in the money market interest rate by 100 basis points, 2007(1)-2012(4). The distance between the two red dotted lines represent the 95 % confidence intervals 49