Document 11530591

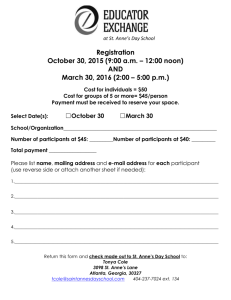

advertisement