Document 11530569

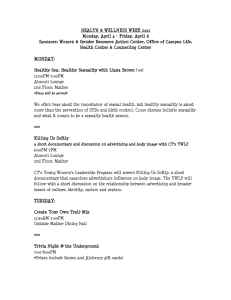

advertisement