Chapter 6.2 — Tests of Significance

advertisement

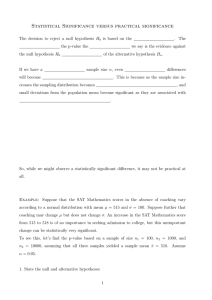

Chapter 6.2 — Tests of Significance Stat 226 – Introduction to Business Statistics I Tests of Significance Example: pick a jury of 12 people randomly out of a pool of 12 men and 12 women Spring 2009 Professor: Dr. Petrutza Caragea Section A Tuesdays and Thursdays 9:30-10:50 a.m. for a fair jury: 6 men and 6 women What about a selection of 5 men and 7 women? Chapter 6, Section 6.2 4 men and 8 women? or even 1 man and 11 women? Test of Significance (Hypothesis testing) Stat 226 (Spring 2009) Introduction to Business Statistics I Section 6.2 Where do we draw the line and no longer believe that the jury selection was truly random and fair? That is when do we start doubting that the chance of getting selected for each gender was truly 50/50? 1 / 27 Chapter 6.2 — Tests of Significance Section 6.2 2 / 27 The philosophy behind a statistical hypothesis test is the same as in a jury trial. There are only two possibilities: “not guilty” corresponding to H0 Hypothesis A hypothesis is a claim or belief about a population parameter that we wish to test. vs. “guilty” corresponding to Ha Like in a jury trial the philosophy is: In any test there are two competing hypotheses: “innocent until proven guilty.” the null hypothesis, denoted by H0 , is a statement of what we assume to be true That is, we assume “not guilty” until we have enough evidence to determine “guilt”. vs. the alternative hypothesis, denoted by Ha , which is a statement against H0 — this is what we want to show Introduction to Business Statistics I Introduction to Business Statistics I Chapter 6.2 — Tests of Significance Some basic terminology Stat 226 (Spring 2009) Stat 226 (Spring 2009) Section 6.2 Likewise we assume H0 is true until we have sufficient evidence in the data in favor of Ha . 3 / 27 Stat 226 (Spring 2009) Introduction to Business Statistics I Section 6.2 4 / 27 Chapter 6.2 — Tests of Significance Chapter 6.2 — Tests of Significance Both, null and alternative hypothesis are always stated in terms of the population parameter. Generally this will be µ for us. Example: Developing a new diet to loose weight (we are interested in the average weight loss in lbs.) we want to see if the diet is effective. Example: A brewery claims that the average content (µ) of their cans of beer is 12 oz, but we suspect that the average content is less (getting ripped off) We want to test H0 : vs. Ha : We want to test H0 : vs. Ha : Example: A machine “in control” should cut wood into 5 feet pieces. It is suspected that machine is “out of control”. We want to test H0 : Stat 226 (Spring 2009) Introduction to Business Statistics I Section 6.2 5 / 27 Stat 226 (Spring 2009) vs. Ha : Introduction to Business Statistics I Chapter 6.2 — Tests of Significance Chapter 6.2 — Tests of Significance In summary we have three different types of alternative hypotheses against the null hypothesis H0 : µ = µ0 Technically, we test Section 6.2 H0 : µ ≤ µ0 vs. Ha : µ > µ0 (instead of H0 : µ = µ0 ) H0 : µ ≥ µ0 vs. Ha : µ < µ0 (instead of H0 : µ = µ0 ) 6 / 27 as well as 1 2 For simplicity we will keep using H0 : µ = µ0 . 3 Note, the “=” sign is always included in the null hypothesis, never in the alternative hypothesis. H0 and Ha always have to contradict each other. earlier we set up the following hypotheses: µ0 corresponds to the mean we assume under H0 Stat 226 (Spring 2009) Introduction to Business Statistics I Example: Brewery claims the mean (average) content of a can of beer is 12 oz. We take a random sample of 36 beer cans and obtain the sample mean x̄ = 11.82 oz. If the standard deviation is known to be σ = 0.38 oz, do we have enough evidence that the brewery is making a false claim? Section 6.2 7 / 27 Stat 226 (Spring 2009) Introduction to Business Statistics I Section 6.2 8 / 27 Chapter 6.2 — Tests of Significance Chapter 6.2 — Tests of Significance If Ha is indeed true, we should expect x̄ to be less than 12 oz. Again, just like in the jury selection example, how much less than 12 oz should x̄ be before we start doubting that µ = 12? Is a mean of x̄ = 11.98 low enough? What about x̄ = 11.22? The question of interest becomes: We can use our knowledge about the sampling distribution of the mean x̄ and the normal calculation from Chapter 1.3 to assess how unusual/unlikely our data and hence the corresponding sample mean is: We need to find P(X̄ ≤ x̄) = P(X̄ ≤ 11.82), i.e. find the probability of obtaining a sample mean that is at least as unusual (in our case as small) as the observed one of x̄ = 11.82 Is a value of x̄ = 11.82 (for a sample of size 36) unusually small if the brewery’s claim of µ = 12 oz is supposed to be true? If so, then this would be evidence against H0 in favor of Ha . Stat 226 (Spring 2009) Introduction to Business Statistics I Section 6.2 9 / 27 Chapter 6.2 — Tests of Significance Stat 226 (Spring 2009) Introduction to Business Statistics I Section 6.2 10 / 27 Chapter 6.2 — Tests of Significance If the brewery claim is true (µ = 12), what do we know about how x̄ behaves for a sample size of n = 36? (sampling distribution) To evaluate evidence in favor of Ha , judge how “unusual” the observed sample mean x̄ = 11.82 is by where it falls on the sampling distribution of x̄ under the null hypothesis. Stat 226 (Spring 2009) Introduction to Business Statistics I Section 6.2 11 / 27 For reference, we then compute a so-called p-value, which is the probability of getting a value at least as unusual as the observed sample mean x̄ assuming that H0 is true. ⇒ p-value measures evidence against H0 Stat 226 (Spring 2009) Introduction to Business Statistics I Section 6.2 12 / 27 Chapter 6.2 — Tests of Significance Chapter 6.2 — Tests of Significance In the brewery example more unusual than x̄ = 11.82 corresponds to x̄ smaller than x̄ = 11.82 (under H0 ) and equivalently smaller than z = −2.84. What is the area to the left of z = −2.84 Handout (How to find p-values) the smaller the p-value the stronger the evidence is against the null hypothesis H0 and in favor of Ha ! Why? — recall the p-value tells us how likely it is to obtain a sample mean as extreme as the observed one if the null hypothesis holds true. So there is only a 0.23% chance of observing a sample mean of 11.82 when H0 : µ = 12 holds true. Stat 226 (Spring 2009) Introduction to Business Statistics I Section 6.2 13 / 27 Chapter 6.2 — Tests of Significance Stat 226 (Spring 2009) Introduction to Business Statistics I Section 6.2 Chapter 6.2 — Tests of Significance How small of a p-value do we need? First Summary of a Hypothesis Test 1 Write H0 and Ha in terms of the parameter µ (the population mean) 2 Assume H0 is true Typically we will make a decision to reject H0 by comparing our p-value to a preselected cut-off value. This cut-off value is called the level of significance and denoted by α. 3 Find z-score for the sample mean x̄ from your data common choices: α = 0.05, α = 0.01 4 Find corresponding p-value (area under the normal curve) So why α = 0.05? What does it imply? 5 if data come from a population that has a different mean than the one assumed under the null hypothesis H0 we will see a small p-value, i.e. our data most likely comes from a different population with a different population mean µ The level of significance corresponds to the error rate that we allow ourselves, saying that in 5% of all decisions we will make the wrong decision, i.e. reject the null hypothesis H0 when in fact H0 is true. Stat 226 (Spring 2009) 14 / 27 Introduction to Business Statistics I Section 6.2 15 / 27 Stat 226 (Spring 2009) Introduction to Business Statistics I Section 6.2 16 / 27 Chapter 6.2 — Tests of Significance Chapter 6.2 — Tests of Significance The choice of α is somewhat subjective — How much of an error probability are we willing to accept? This is equivalent to how strong your evidence against H0 has to be before you are willing to reject H0 . Decision Rule If we chose α = 0.01, we would commit the error only 1% of the times, but it would be harder to reject the null hypothesis (x̄ will have to be more extreme before we can reject H0 ) if p-value ≤ α, reject H0 in favor of Ha We say: We have statistically significant evidence against H0 and have reason to believe in Ha if p-value > α, fail to reject H0 We say: We do not have sufficient evidence against H0 and no reason to believe in Ha Stat 226 (Spring 2009) Introduction to Business Statistics I Section 6.2 17 / 27 Stat 226 (Spring 2009) Introduction to Business Statistics I Chapter 6.2 — Tests of Significance Chapter 6.2 — Tests of Significance Example: α = 0.05 (level of significance) A technical & philosophical note: We say any p-value ≤ 0.05 is statistically significant at the 0.05 level. Section 6.2 18 / 27 the decision is always in terms of the null hypothesis H0 ; we either are able to“reject H0 ” or we “fail to reject H0 ” Example: Suppose p-value=0.03 we never prove neither H0 nor Ha , we just collect evidence against H0 . If we fail to find strong evidence against H0 , we will “stick to H0 ”. This does not imply that H0 is necessarily true, maybe we just did not have a sufficiently large sample size if α = 0.05: On the other hand, rejecting H0 in favor of Ha does not guarantee that Ha is true despite very strong evidence. if α = 0.01: For any given hypothesis test, there is two kind of errors we can commit, but we also a very high chance of making a correct decision: Stat 226 (Spring 2009) Introduction to Business Statistics I Section 6.2 19 / 27 Stat 226 (Spring 2009) Introduction to Business Statistics I Section 6.2 20 / 27 Chapter 6.2 — Tests of Significance Chapter 6.2 — Tests of Significance Type I and Type II error in Hypotheses Tests Handouts (“z-procedure” & Examples) Stat 226 (Spring 2009) Introduction to Business Statistics I Section 6.2 21 / 27 Chapter 6.2 — Tests of Significance Stat 226 (Spring 2009) Introduction to Business Statistics I Section 6.2 22 / 27 Chapter 6.2 — Tests of Significance Connection between confidence intervals and two-sided hypotheses tests (p.394/395) Let’s see what decision we will obtain by conducting the corresponding hypothesis test: Recall the example of water bottling company Water bottles are supposed to contain 710 ml on average, σ = 6 ml and a sample of 90 bottles yielded an average of 708 ml. Example: Is the bottling process still on target? We constructed a 98% CI for µ and obtained (706.53 ; 709.47) We concluded intuitively, that this is a good indicator that the process is not on target any longer. — Was this intuitive decision justified? Stat 226 (Spring 2009) Introduction to Business Statistics I Section 6.2 23 / 27 Stat 226 (Spring 2009) Introduction to Business Statistics I Section 6.2 24 / 27 Chapter 6.2 — Tests of Significance Chapter 6.2 — Tests of Significance What is the connection? A two-sided hypothesis test using a significance level α and a (1 − α) ∗ 100% confidence interval are equivalent. That is, a two-sided hypothesis test rejects the null hypothesis H0 exactly when the value µ0 falls outside the corresponding (1 − α) ∗ 100% confidence interval Stat 226 (Spring 2009) Introduction to Business Statistics I Section 6.2 25 / 27 Chapter 6.2 — Tests of Significance Practical versus Statistical Significance Handout Stat 226 (Spring 2009) Introduction to Business Statistics I Section 6.2 27 / 27 Stat 226 (Spring 2009) Introduction to Business Statistics I Section 6.2 26 / 27