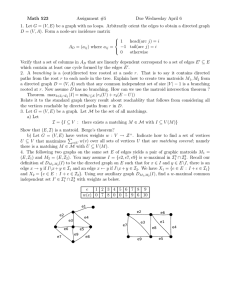

On the normality of giant components Taral Guldahl Seierstad University of Oslo

advertisement

On the normality of giant components

Taral Guldahl Seierstad

University of Oslo

November 19, 2008

Abstract

We consider a general family of random graph processes, which begin with an empty

graph, and where at every step an edge is added at random according to some rule. We

show that when certain general conditions are satisfied, the order of the giant component

tends to a normal distribution.

1

Introduction

We consider discrete random graph processes, where the initial state typically is an empty

graph on n vertices, and where, at every step, an edge is added at random, according to

some given rule. The standard example of such graph processes is the model introduced

by Erdős and Rényi [5], where at every step the edge to be added is chosen uniformly at

random from all edges which are not already present in the graph. We use the notation

GER

n,m to denote the state in the Erdős–Rényi graph process on n vertices after m edges have

been added.

An interesting phenomenon in this graph process is the emergence of the so-called giant

component: Erdős and Rényi [5] showed that when cn edges have been added and c > 1/2,

then asymptotically almost surely (i.e. with probability tending to 1 as n tends to infinity,

abbreviated a.a.s.) there is a unique component with Θ(n) vertices, whereas the second

largest component has Θ(ln n) vertices. In fact they showed that if Γn,m is the order of

p

−1

the largest component in GER

Γn,cn → d, where d is the number

n,m , and c > 1/2, then n

between 0 and 1 such that d + e−2cd = 1.

Later, Pittel [10] showed that Γn,cn tends to a normal distribution; that is, there is a

constant σ, depending on c, such that

Γn,cn − dn d

√

→ N (0, σ 2 ),

n

where N (0, σ 2 ) denotes the probability distribution of a normal random variable with mean 0

and variance σ 2 . Such central limit theorems for the giant component have interested several

authors, in particular in relation to the similar random graph model G(n, p). For that graph

model a central limit theorem was first found by Stepanov [16], and it has been reproved

several times. In fact, Pittel’s proof in [10] also works for this model. Another proof is due

to Barraez, Boucheron and Fernandez de la Vega [2] who used a random walk approach. For

hypergraphs, the problem has been studied by Behrisch, Coja-Oghlan and Kang [3], who

proved a similar theorem.

1

In this paper we consider a wide family of random graph processes, which includes GER

n,m ,

and we show that a central limit theorem holds for these processes as well, provided that

certain conditions are satisfied. The main requirement of our method is that at every

stage in the graph process, the probability that the next edge to be added is incident to

a particular component depends only on certain features of the component, such as the

number of vertices in the component, or the degrees of the vertices in the component. This

is satisfied by several random graph processes which have been studied earlier; in particular,

in Section 4, we will consider the so-called minimum-degree graph process [18, 7, 8] in detail.

In Section 5 we will discuss some other graph processes for which this technique may work.

Note that we will not prove that these graph processes actually have a giant component; we

will merely show that if there is a giant component, then the number of vertices it contains

is asymptotically normally distributed.

In order to prove a central limit theorem for the giant component in this more general

setting, we will use an approach similar to that of Pittel [10]. A central ingredient in

our proof is the so-called differential equation method. Wormald [17, 18] used differential

equations as a general way to prove laws of large numbers for random variables defined on

graph processes. This was extended to a central limit theorem by Seierstad [13], and this

theorem will be used to prove the main theorem of the present paper.

In Section 2 we present the differential equation method to be used in the proof. The

theorem we present is a generalization of the main theorem in [13]; the proof is found

in Section 6. In Section 3 a rather general method to prove that the giant component has

asymptotically normal distribution is presented. The method requires a number of conditions

to be satisfied in order to function. Therefore, in Section 4, we apply it to the minimum

degree graph process, thereby showing that it actually can be used in real problems. In

Section 5 we briefly discuss some other processes to which the method can be applied.

2

The differential equation method

Let (Ωn , Fn , Pn ) be a sequence of probability spaces, and assume that a filtration Fn,0 ⊆

Fn,1 ⊆ · · · ⊆ Fn,mn ⊆ Fn is given for every n ≥ 1, where mn = O(n). Let q ≥ 1

be a fixed number and let Xn,m,1 , . . . , Xn,m,q be Fn,m -measurable random variables. Let

X n,m = [Xn,m,1 , . . . , Xn,m,q ]0 , where v 0 denotes the transpose of v, and let ∆Xn,m,k =

Xn,m,k − Xn,m−1,k for 1 ≤ m ≤ mn and 1 ≤ k ≤ q. If Σ is a q × q-matrix, N (0, Σ)

denotes the multivariate normal distribution with mean 0 and covariance matrix Σ; if σ is a

constant, N (0, σ 2 ) denotes the univariate normal distribution with mean 0 and variance σ 2 .

Asymptotic statements are meant to hold as n → ∞.

Wormald [17, 18] developed the differential equation method: provided that the random

variables satisfy certain conditions, they converge in probability to the solution of some

differential equations. Seierstad [13] extended this method by showing that if further conditions are satisfied, then the random variables converge jointly to a multivariate normal

distribution. The following theorem is a combination of Theorem 5.1 of Wormald [18] and

the main theorem of Seierstad [13], with a slight generalization to allow for random initial

states.

(n)

Theorem 1. Assume that there is a constant C0 such that Xm,k ≤ C0 n for all n, 0 ≤ m ≤

mn and 1 ≤ k ≤ q. Let fk , gij : Rq → R, 1 ≤ i, j, k ≤ q, be functions. Assume that there is

a constant vector µ0 and a constant q × q-matrix Σ0 such that

X 0 − nµ0 d

√

→ N (0, Σ0 ).

n

2

(1)

Let D be a bounded connected open set containing the closure of

(n)

{(z1 , . . . , zq ) : P[X0,k = zk n, 1 ≤ k ≤ q] 6= 0

for some n},

and let HD = HD (X n,m ) be the random variable denoting the minimum m such that

n−1 X n,m ∈

/ D. Assume that the following conditions hold.

(i) For some function β = β(n), with 1 ≤ β = o(n1/12−ε ) for some ε > 0, we have

(n)

∆Xm,i ≤ β, for 1 ≤ m < HD and 1 ≤ i ≤ q.

(ii) For some function λ1 (n) = o(n−1/2 ), and all i ≥ 1 and 1 ≤ m < HD ,

(n)

E[∆Xm,i | Fm−1 ] − fi (n−1 Xm−1,1 , . . . , n−1 Xm−1,q ) ≤ λ1 (n).

(iii) For some function λ2 (n) = o(1), and all i, j ≥ 1 and 1 ≤ m < HD ,

(n)

(n)

E[∆Xm,i ∆Xm,j | Fm−1 ] − gij (n−1 Xm−1,1 , . . . , n−1 Xm−1,q ) ≤ λ2 (n).

(iv) Each function fi is continuous and differentiable, with continuous derivatives, and

satisfies a Lipschitz condition on D.

(v) Each function gij is continuous and satisfies a Lipschitz condition on D.

Then the following are true.

(a) For (ẑ1 , . . . , ẑq ) ∈ D, the system of differential equations

dzk

= fk (z1 , . . . , zq ),

dt

k = 1, . . . , q,

has a unique solution in D for zk : R → R passing through zk (0) = ẑk , 1 ≤ k ≤ q, and

which extends to points arbitrarily close to the boundary of D.

(b) Let F : Rq → Rq be the function F (z) = [f1 (z), . . . , fq (z)]0 , and let G : Rq → Rq×q be

the function G(z) = {gij (z)}ij . Let α : R → Rq be the unique function satisfying

d

α(t) = F (α(t))

dt

∂fi

with α(0) = µ0 and let J(z) = { ∂z

}i,j be the Jacobian matrix of F . Let T (t) be the

j

q × q-matrix satisfying the differential equation

d

T (t) = −T (t)J(α(t)),

dt

Let

Z

Ξ(t) = Σ0 +

T (0) = I.

(2)

t

T (s)(G(α(s)) − F (α(s))2 )T (s)0 ds

(3)

0

and let Σ(t) = T (t)−1 Ξ(t)(T (t)0 )−1 . If

(n)

(n)

Ym,k =

Xm,k − nαk (m/n)

√

n

(n)

(n)

0

for 1 ≤ k ≤ q, and Y (n)

m = [Ym,1 , . . . , Ym,q ] , then

d

Y (n)

m → N (0, Σ(m/n)),

3

(4)

for 0 ≤ m ≤ σn ≤ mn , where σ = σ(n) is the supremum of those m to which the

solution α can be extended before reaching within L∞ -distance Cλ of the boundary

of D, for a sufficiently large constant C. Moreover, the convergences (1) and (4)

occur jointly.

This theorem is proved in [13] for the case that Σ0 is the zero matrix. A modification

of the proof is necessary to allow for nonzero initial covariance matrices. The reason that

we include this generalization is that it is necessary for studying the minimum-degree graph

process in Section 4; for most typical graph processes however, the generalization is not

needed. Since this is not the central theme of the paper, we defer the proof of Theorem 1

to Section 6.

3

General theorem

Let {Gn,m }m≥0 be a Markov process, whose states are graphs on n vertices.

Let T1 , T2 , . . . be classes of trees such that every tree is a member of Tk for exactly one k.

We require that all the trees in a given class have the same number of vertices, and we let

ck be the number of vertices in the trees contained in Tk . Furthermore, we assume that the

sequence (c1 , c2 , . . .) is non-decreasing and that the number of integers i such that ci = k is

at most k γ for some γ ≥ 0.

(n)

Let Tm,k be the random variable denoting the number of components in Gn,m which are

(n)

(n)

(n)

members of Tk . Let ∆Tm,k = Tm,k − Tm−1,k .

For δ > 0, let Lδ = Lδ,{ck } be the Banach space of all sequences x = (x1 , x2 , . . .) with

the norm

X

kxk =

cδk |xk | < ∞.

k≥1

(q)

Theorem 2. For every q ≥ 1, let functions fi

(q)

: Rq → R and gij : Rq×q → R be given

(q)

(q 0 )

for 1 ≤ i, j ≤ q. Assume that if q > q 0 ≥ i, then fi (z1 , . . . , zq ) = fi

(z10 , . . . , zq0 0 ) and if

(q 0 )

gij (z10 , . . . , zq0 0 ),

(q)

gij (z1 , . . . , zq )

q > q 0 ≥ max(i, j), then

=

whenever zk = zk0 for 1 ≤ k ≤ q.

Assume furthermore that for every fixed q ≥ 1, the conditions of Theorem 1 are satisfied,

(n)

(n)

with Xm,k = Tm,k and for some D = Dq ⊆ Rq . Let t be a constant, and let m = btnc.

Assume that there are constants K, C 0 and ρ with 0 < ρ < 1, possibly depending on t, such

that

(n)

ETm,k ≤ Knρck

and

(n)

Var Tm,k ≤ Knρck .

Then there exist continuous functions µi (t) and σij (t) for i, j ≥ 1, and jointly normal

variables W1 (t), W2 (t), . . . such that EWi (t) = 0 and Cov(Wi (t), Wj (t)) = σij (t) and such

that the following hold.

a. Let

(n)

(n)

Um,k

Tm,k − nµk (t)

√

=

n

for k ≥ 1. If q ≥ 1 is fixed, then

(n)

d

Um,k → Wk (t)

jointly for 1 ≤ k ≤ q and 0 ≤ m ≤ σn ≤ mn , where σ = σq is as in Theorem 1.

4

(n)

(n)

∗

b. Let U (n)

m = (Um,1 , Um,2 , . . .) and W (t) = (W1 (t), W2 (t), . . .) and σ = inf q σq . Then,

(n)

for 0 ≤ m ≤ σ ∗ n, W (t) ∈ Lδ a.s., and U m converges to W (t) in distribution; that

is, for every bounded continuous functional h on Lδ , h(U (n)

m ) converges in distribution

to h(W (t)).

(n)

c. Let Zm be the number of vertices contained in components which are not trees. Then

there are continuous functions µ(t) and σ(t) such that for 0 ≤ m ≤ σ ∗ n,

(n)

Zm − nµ(t) d

√

→ N (0, σ(t)).

n

(n)

d. Let Γm be the random variable denoting the number of vertices in the largest compo(n)

nent in Gn,m , and let Cm be the random variable denoting the number of vertices in

√

(n)

cyclic components, except for the largest component. Assume that Cm = o( n) a.a.s.

Then, for 0 ≤ m ≤ σ ∗ n,

(n)

Γm − nµ(t) d

√

→ N (0, σ(t)).

n

Proof. In our proof, (a) is proved by the differential equation method, while the proof of (b)

follows the proof by Pittel [10]. Finally, (c) and (d) follow from (b).

(q)

(q)

Henceforth we will suppress the dependence on n. The conditions imply that fi and gij

are essentially the same for all values of q; we therefore refer to these functions as fi and gij

and we note that fi only depends on z1 , . . . , zi and gij only depends on z1 , . . . , zmax(i,j) .

Thus, the functions µi (t) and σij (t), which we obtain by the differential equation method

will be the same, regardless of the value of q. Conclusion (a) then follows directly from

Theorem 1.

In order to prove (b) we first have to show that W (t) ∈ Lδ a.s. for δ > 0. By Jensen’s

d

2

inequality, E[|Um,k |]2 ≤ E[Um,k

]. Moreover, by (a), Um,k → N (0, σk2 ), for some σk ≥ 0, so

E[Um,k ] = o(1) as n → ∞. Then

(n)

E[|Um,k |]2 ≤ Var[Um,k ] + E[Um,k ]2

= Var

Tm,k − nµk (m/n)

√

+ o(1)

n

= n−1 Var Tm,k + o(1) ≤ Kρck + o(1).

√

ρ < ρ0 < 1. Then, by Markov’s inequality,

√ c /2

E|Um,k |

Kρ k + o(1)

0 ck

P[|Um,k | > ρ ] ≤

≤

= Kθck + o(1),

ρ0ck

ρ0ck

√

where 0 < θ = ρ/ρ0 < 1. By (a), for every a, P[|Wm,k | > a] = limn→∞ P[|Um,k | > a], so

Let ρ0 be a constant such that

X

c

P[|Wk (t)| > ρ0 k ] ≤ K

X

θ ck ≤ K

k≥1

k≥1

X

k γ θk < ∞.

k≥1

c

By the Borel–Cantelli lemma, there is a.s. a k0 such that for all k ≥ k0 , |Wk (t)| ≤ ρ0 k .

Hence,

X

X

k

cδk |Wk (t)| ≤

k δ+γ ρ0 < ∞,

k≥k0

k≥ck0

5

so W (t) ∈ Lδ a.s.

In order to prove that U m tends to W (m/n) in distribution, we have to show the

following. (See Billingsley [4].)

(i) Convergence of the finite-dimensional distributions. For any selection of k positive

integers i1 , . . . , ik , where k ≥ 1, the vector [Um,i1 , . . . , Um,ik ] converges in distribution

to [Wi1 (t), . . . , Wik (t)] as n tends to infinity.

(ii) Tightness. For every ε > 0 there exists a compact subset K(ε) of Lδ such that

P[U 6∈ K(ε)] < ε for every n.

Convergence of the finite-dimensional distributions follows from (a), so it remains to

show that (ii) holds. Let

√

K(ε) = {x ∈ Lδ : |xk | ≤ ε−1 3 ρck },

which is a compact set. By Chebyshev’s inequality, for ν > 0,

P[|Um,k | > ν] ≤

Var Tm,k

Var Um,k

Kρck

=

.

≤

ν2

ν2n

ν2

Hence,

P[U m ∈

/ K(ε)] ≤

X

X

√

√

P[|Um,k | > ε−1 3 ρck ] ≤

Kε2 3 ρck = O(ε2 ).

k≥1

k≥1

P

Therefore the tightness condition is met, and (b) follows. If we define h(x) = k≥1 ck xk ,

this function is clearly bounded on L1 , so h(U (n)

m ) converges in distribution to h(W (t)).

Since

X

Zm = n −

ck Tm,k ,

k≥1

we see that (c) follows directly

from (b).

√

Finally, since Cm = o( n) a.a.s. and Γm = Zm − Cm ,

Γm − nµ(t)

Zm − nµ(t)

√

√

P

>a =P

> a + o(1),

n

n

so n−1/2 (Γm − nµ(t)) and n−1/2 (Zm − nµ(t)) converge to the same distribution.

Theorem 2 is adequate for graph processes such as GER

n,m , where the probability that

the next edge chosen is incident to a particular component depends only on the type of

the component. However, we can also allow the probability to depend on other random

variables, such as the total number of vertices of degree k, say, in the graph, provided that

these random variables also behave nicely, and can be subjected to the differential equation

method.

(n)

(n)

Theorem 3. Let Dm,1 , Dm,2 , . . . be Fn,m -measurable random variables, and let

(n)

(n)

(n)

(n)

Φ = {Dm,1 , Dm,2 , . . .} ∪ {Tm,1 , Tm,2 , . . .}.

(n)

(n)

Order the elements of Φ, and write Φ = (Xm,1 , Xm,2 , . . .), so that each Xm,k is equal to

Dm,i or Tm,i for some i. Assume that the random variables in Φ have been ordered in such

(n)

(n)

a way that Theorem 1 can be applied to any initial segment Φq := (Xm,1 , . . . , Xm,q ) of Φ.

Assume furthermore, that the conditions of Theorem 2 are otherwise satisfied. Then the

conclusions of Theorem 2 hold.

6

Proof. We observe that the differential equation can be applied to the random variables

in Φq . Thus, the proof of Theorem 2 can be applied virtually unchanged.

A number of conditions must be satisfied in order for Theorem 2 or Theorem 3 to be

applied. In the next section we consider a concrete example — the minimum degree graph

process — in order to demonstrate that the procedure explained in this section actually is

practical to apply to real graph processes.

The differential equation method provides an explicit formula for the mean µ(t) and the

covariance matrix Σ(t). In principle it is calculate the functions µ(t) and σ(t) from µ(t) and

Σ(t), but in many cases this will be unfeasible. So although we can show that the order of

the giant component is asymptotically normally distributed, our method is not necessarily

suitable for calculating the actual parameters of the normal distribution.

4

The minimum degree graph process

We will now apply the method of the previous section to the minimum degree graph process,

which was introduced by Wormald [18]. Let Gmin

n,0 be the empty graph on n vertices, and

for

m

≥

1

be

obtained

in

the

following

way: Choose first a vertex v in Gmin

let Gmin

n,m

n,m−1

uniformly at random from the set of vertices of minimum degree; then choose a vertex w

uniformly at random from the set of vertices distinct from v. Note that w may have any

min

degree. Let Gmin

n,m be the graph on n vertices consisting of all edges in Gn,m−1 in addition

to the edge vw.

Let h1 = ln 2 ≈ 0.69 and h2 = ln 2 + ln(1 + ln 2) ≈ 1.22, and let t = n/m. Kang et al. [7]

showed that if t is a fixed number with 0 ≤ t < h1 , then the minimum degree is a.a.s. 0; if

h1 < t < h2 , then the minimum degree is a.a.s. 1; and if t > h2 , then the minimum degree

is a.a.s. at least 2. Moreover, they showed that if t > h2 , then the largest component a.a.s.

has n − o(n) vertices, and the graph is in fact connected with probability bounded away

from 0.

Moreover, it was shown by Kang and Seierstad [8] that there is a phase transition at the

2−2

≈ 0.86. That is, when t < hg , the largest component

point hg = ln 2 ln 2−1+16√ln27−16

ln 2 ln 2

a.a.s. has order Θ(ln n), whereas when t > hg , the largest component a.a.s. has order Θ(n),

while every other component a.a.s. has order O(ln n). Although not explicitly stated, it is

implied by the proof in [8] that there is a function µ(t) such that if Γn,tn is the number

p

−1

of vertices in the largest component in Gmin

Γn,tn → µ(t) when t ∈ (hg , h2 ).

n,tn , then n

(See Seierstad [14].) Moreover, a formula for µ(t) was given in [8]. Here we will show the

following theorem.

Theorem 4. There are functions µ(t) and σ(t), which are continuous on (hg , h2 ), such that

Γn,tn − nµ(t) d

√

→ N (0, σ(t))

n

for hg < t < h2 .

Due to some complications explained below, specific to this graph process, we cannot

apply Theorem 2 or Theorem 3 directly. However, the general method explained in Section 3

can be used. For reasons explained in Section 4.1 we will split the trees into classes depending

on their order and number of leaves; thus Tk,l is the set of trees of order k with l leaves, and

we let Tm,k,l be the random variable denoting the number of trees in Gmin

n,m with k vertices

and l leaves. The fact that we use two indices instead of one is only for convenience, and

7

has no effect on the argument. By considering the proof of Theorem 2, we see that in order

to prove Theorem 4 it is sufficient to show that the following three conditions are satisfied.

1. Any finite number of the random variables Tm,k,l converge jointly to a multivariate

normal distribution.

2. There are constants K > 0 and ρ with 0 < ρ < 1 such that ETm,k,l ≤ Knρk and

Var Tm,k,l ≤ Knρk .

3. Let Cn,m be the random

variable denoting the number of vertices in cyclic components.

√

Then ECn,m = o( n).

These three conditions will be shown to hold in the next three sections.

4.1

Applying the differential equation method

From now on, we will write Gn,m for Gmin

n,m . Assume that t is a fixed number with 0 ≤ t < h2 .

If 0 ≤ t < hg , then the graph consists a.a.s. of small components of order O(ln n). If

hg < t < h2 , there is a.a.s. a giant component, but a positive proportion of the vertices is

contained in components of order O(ln n).

Let C be a component in Gn,m , and suppose vw is the next edge to be added to the

process, with v chosen first and w second. The probability that w is contained in C is

proportional to the number of vertices in C. When the minimum degree is 0, v must be an

isolated vertex; when the minmum degree is 1, the probability that v is contained in C is

proportional to the number of leaves in C. Thus, we should define the classes Tk in terms

of both the number of vertices and the number of leaves. It is then most practical to use

two indices. We define a leaf to be a vertex of degree 0 or 1; thus, an isolated vertex is

considered to be a leaf. We let Λ be the set of pairs (k, l) for which there exists at least one

tree with k vertices and l leaves; in other words

Λ = {(1, 1)} ∪ {(2, 2)} ∪ {(k, l); k ≥ 3, 2 ≤ l ≤ k − 1}.

For (k, l) ∈ Λ, let Tk,l be the set of trees which have k vertices and l leaves. Clearly, every

tree is in exactly one class, and there are max(1, k − 2) classes of trees with k vertices, so

this partition satisfies our conditions.

For (k, l) ∈ Λ, let Tm,k,l be the number of tree components in Gn,m which are of type Tk,l .

We also define Tm,k,l = 0 whenever (k, l) ∈

/ Λ, so that we do not need to be so careful with

the bounds on the summation indices. In order to use the differential equation method,

we should now express the expected change ∆Tm,k,l by functions fk,l ; however, here we

encounter a problem, since the functions fk,l are different when there are vertices of degree 0

in the graph, and when the minimum degree is 1. Thus, the functions fk,l are not necessarily

continuous at t = h1 .

We therefore consider the graph process in two phases: the first when the minimum

degree is 0, and the second when the minimum degree is 1.

This graph process was studied in [7] and [8], and we will use some of the calculations

from those papers, which we summarize here:

Lemma 5. Let H be the random variable denoting the smallest integer for which Gn,H

has minimum degree 1, and let Lm be the random variable denoting the number of vertices

p

p

of degree 1 in Gn,m . Then n−1 H → ln 2, n−1 LH → ln 2 and there are constants µk,l

p

for (k, l) ∈ Λ such that n−1 TH,k,l → µk,l , with µ1,1 = 0 and µk,l > 0 for (k, l) 6= (1, 1).

Moreover, there is a continuous function b(t) with b(t) > 0 for t ∈ (0, h2 ) and b(t) = 0

p

otherwise, such that for t = m/n, n−1 Lm → b(t).

8

p

p

Proof. In [7] it was shown that n−1 H → ln 2 and n−1 LH → ln 2. Let Rm,k be the number

of trees in Gn,m of order k. In [8] it was shown that there are constants ρk with ρ1 = 0 and

p

ρk > 0 for k > 1, such that n−1 RH,k → ρk . Moreover it was shown that there are constants

pk,l > 0 for (k, l) ∈ Λ such that if C is an arbitrary component with order k, then it has

p

exactly l leaves with probability pk,l . It follows that n−1 TH,k → µk,l where µk,l = pk,l ρk ,

and that µk,l = 0 for (k, l) = (1, 1) and µk,l > 0 for (k, l) ∈ Λ\{(1, 1)}. Finally, the existence

of b(t) was shown in [7].

The next lemma shows that these random variables also satisfy a central limit theorem:

they converge jointly to normal random variables.

Lemma 6. Let Λ∗ be a finite subset of Λ. There are jointly normal random variables

d

d

η, χ and {Uk,l }(k,l)∈Λ∗ such that n−1/2 (H − n ln 2) → η, n−1/2 (LH − n ln 2) → χ and

d

n−1/2 (TH,k,l − µk,l n) → Uk,l for all (k, l) ∈ Λ∗ jointly as n → ∞.

Proof. We can assume without loss of generality that Λ∗ is on the form {(k, l) ∈ Λ; k ≤ q}

for some fixed integer q.

The proof uses Theorem 1; however, there is a complication, since we want to determine

the distribution of the random variables with respect to the random stopping time H. In

order to make sure that Theorem 1 can be used, we would prefer that the process continues

◦

which are

smoothly also some time after H. Below we will introduce random variables Tm,k,l

identical to Tm,k,l when m ≤ H, but which continue smoothly also some time after m = H.

∗

∗

∗

We will now find functions f(k,l) : RΛ → R and g(k,l),(k0 ,l0 ) : RΛ ×Λ → R such that

E[∆Tm,k,l | Fm−1 ] = f(k,l) ({n−1 Tm,κ,λ }(κ,λ)∈Λ∗ ) + o(n−1/2 )

(5)

E[∆Tm,k,l ∆Tm,k0 ,l0 | Fm−1 ] = g(k,l),(k0 ,l0 ) ({n−1 Tm,κ,λ }(κ,λ)∈Λ∗ ) + o(1).

(6)

and

Assume that m ≤ H, and let vm wm be the mth edge added in the graph process. When

we talk about the properties of vm and wm , we always mean their properties as vertices

in Gn,m−1 . Then vm is necessarily an isolated vertex, while wm can be in any type of

component. The probability that wm is in a particular component is proportional to the

order of the component. Let Wm ∈ Λ × {1, 2} be the random vector containing the relevant

characteristics of wm : We let Wm = (κ, λ, d) if wm is contained in a component of order κ

with λ leaves and d = 1 if wm is a leaf and d = 2 otherwise. Then, for (κ, λ) ∈ Λ∗ and

d = 1, 2,

λTm−1,κ,λ − δκ1

P[Wm = (κ, λ, 1) | Fm−1 ] =

(7)

n−1

and

(κ − λ)Tm−1,κ,λ

P[Wm = (κ, λ, 2) | Fm−1 ] =

.

(8)

n−1

Define

−δkκ δlλ + δk,κ+1 δl,λ+d−1 if (k, l) ∈ Λ \ {(2, 2)},

(d)

−δκ2 δλ2 + δκ1 δλ1

if (k, l, d) = (2, 2, 1),

ζk,l (κ, λ) =

0

otherwise.

If Wm = (κ, λ, d), then

(d)

∆Tm,k,l = −δk1 + ζk,l (κ, λ).

(9)

To see that this holds, note that if w is contained in a (κ, λ)-component with κ ≥ 2, then

we lose a component of type (κ, λ). On the other hand, we gain a component with κ + 1

9

vertices, where the number of leaves is λ if w is a leaf, and λ + 1 if w is not a leaf. The

case (κ, λ) = (1, 1) is a bit different, since we then get a component with two vertices and

λ + 1 = 2 leaves, even though w is a leaf itself. Finally, δk1 is subtracted, since an isolated

vertex disappears at every step. Thus,

X

(d)

E[∆Tm,k,l | Fm−1 ] = − δk1 +

P[Wm = (κ, λ, d) | Fm−1 ]ζk,l (κ, λ)

κ,λ,d

= − δk1 +

X λTm−1,κ,λ

n

κ,λ

+

X (κ − λ)Tm−1,κ,λ

n

κ,λ

(1)

ζk,l (κ, λ)

(10)

(2)

ζk,l (κ, λ) + o(n−1/2 ).

Note that only a finite number of the summands are nonzero, so the sums are well-defined.

(d)

Furthermore ζk,l (κ, λ) = 0 whenever κ > k or λ > l, so we obtain an expression on the

form (5). In a similar manner, we obtain

Tm,1,1

Tm,1,1

2

(−2) + 1 −

(−1)2 + o(1)

E[∆Tm,1,1 ∆Tm,1,1 | Fm−1 ] =

n

n

(11)

3Tm−1,1,1

=

+ 1 + o(1),

n

and if k > 1,

E[∆Tm,1,1 ∆Tm,k,l | Fm−1 ]

X λTm,κ,λ

X (κ − λ)Tm,κ,λ

(1)

(2)

=

(−1 − δκ1 )ζk,l (κ, λ) +

(−1)ζk,l (κ, λ) + o(1).

n

n

κ,λ

(12)

κ,λ

Finally, if k, k 0 > 1,

E[∆Tm,k,l Tm,k0 ,l0 | Fm−1 ]

(13)

X

X λTm−1,κ,λ (1)

(κ − λ)Tm−1,κ,λ (2)

(1)

(2)

ζk,l (κ, λ)ζk0 ,l0 (κ, λ) +

ζk,l (κ, λ)ζk0 ,l0 (κ, λ) + o(1).

=

n

n

κ,λ

κ,λ

Hence, we also have found expressions on the form (6), so Conditions (ii) and (iii) of

∗

Theorem 1 are satisfied. We then have to find a domain D ∈ RΛ on which the functions f

and g satisfy a Lipschitz condition. Since the functions are all linear, this is simple: we always

∗

have 0 ≤ n−1 Tm,k,l ≤ 1, so we can define D = {{z(k,l) }(k,l)∈Λ∗ ∈ RΛ ; −ε < zk,l < 1 + ε} for

any ε > 0. The functions f(k,l) and g(k,l),(k0 ,l0 ) then clearly satisfy Conditions (iv) and (v).

Finally, since |∆Tk,l | ≤ 2 always, Condition (i) is satisfied. Hence, we can apply Theorem 1.

We conclude that for every t with 0 < t < h1 there are functions µk,l (t) and jointly normal

d

∗

∗

random variables Uk,l

(t) for (k, l) ∈ Λ∗ such that n−1/2 (Ttn,k,l − nµk,1 (t)) → Uk,l

(t) jointly.

Our aim is to show that Tm,k,l also converges to a normal distribution for the random

◦

time m = H. To this end we define random variables Tm,k,l

for m ≥ 0 and (k, l) ∈ Λ∗ which

behave like Tm,k,l when m ≤ H, but whose behaviour does not change abruptly as soon as

◦

m > H. We assume that m ≤ hn + o(n). We first define a random variable Wm

as follows.

◦

For 1 ≤ m ≤ H, let Wm = Wm . For m > H, we let

◦

P[Wm

= (κ, λ, 1) | Fm−1 ] =

10

◦

λ|Tm−1,κ,λ

| − δκ1

n−1

(14)

and

◦

P[Wm

= (κ, λ, 2) | Fm−1 ] =

◦

(κ − λ)|Tm−1,κ,λ

|

.

n−1

(15)

◦

◦

We define Tm,k,l

such that if Wm

= (κ, λ, d), then

(d)

◦

◦

∆Tm,k,l

= −δk1 + ζk,l (κ, λ) sgn(Tm−1,κ,λ

).

Then

◦

E[∆Tm,k,l

| Fm−1 ]

X

(d)

◦

◦

= − δk1 +

P[Wm

(κ, λ, d)] | Fm−1 ]ζk,l (κ, λ) sgn(Tm−1,κ,λ

)

κ,λ,d

= − δk1 +

◦

X λ|Tm−1,κ,λ

| − δκ1

n−1

κ,λ

+

◦

X (κ − λ)|Tm−1,κ,λ

|

n−1

κ,λ

= − δk1 +

◦

X λTm−1,κ,λ

κ,λ

n

(1)

◦

ζk,l (κ, λ) sgn(Tm−1,κ,λ

)

(2)

◦

ζk,l (κ, λ) sgn(Tm−1,κ,λ

) + o(n−1/2 )

(1)

ζk,l (κ, λ) +

◦

X (κ − λ)Tm−1,κ,λ

κ,λ

n

(2)

ζk,l (κ, λ) + o(n−1/2 ),

◦

which is the same as (10) except that Tm−1,κ,λ is exchanged with Tm−1,κ,λ

. Similarly, (11)

◦

◦

and (12) hold when Tm−1,κ,λ is exchanged with Tm−1,κ,λ , since |Tm−1,κ,λ

| is multiplied

◦

by sgn(Tm−1,κ,λ

) whenever it appears. It is not so clear that (13) holds, since the terms

◦

◦

sgn(Tm−1,κ,λ

) will be squared; thus Tm−1,κ,λ in (13) must be exchanged with |Tm−1,κ,λ

|,

p

◦

rather than Tm−1,κ,λ

. However, according to Lemma 5, we have n−1 Tm,k,l → µk,l > 0

whenever κ > 1 and (k, l) ∈ Λ, so for these values of k and l, Tm−1,k,l is a.a.s. positive. The

p

only problem therefore lies in the terms where κ = 1, since, by Lemma 5, n−1 Tm−1,1,1 → 0, so

Tm−1,1,1 may be either positive or negative. But when m = hn+o(n), we have Tm,1,1 = o(1)

a.a.s., so this case is consumed by the error term in (13). Hence all the equations (10) to (13)

hold for T ◦ as well, and we can apply Theorem 1. Hence, there are jointly normal random

d

∗

◦

◦

◦

◦

(t) = Uk,l

(t)

(m/n) for 0 < t < h1 +o(1). Clearly Uk,l

variables Uk,l

(t) such that Tm,k,l

→ Uk,l

when t < h1 .

◦

The random variables we are looking for are TH,k,l = TH,k,l

, and we will now show

that these random variables also converge jointly to a jointly normal distribution. Since we

d

◦

2

have limt→h− µ1,1 (t) = 0, we see that n−1/2 Th◦1 n,1,1 → U1,1

∼ N (0, σ1,1

), for some constant

1

√

0

σ11 > 0. Let m = h1 n + c √n, where c is a constant, either positive or negative. Then

◦

we have a.a.s. |Tm

n). Let m1 = min(m0 , h1 n) and m2 = max(m0 , h1 n). Let

0 ,1,1 | = O(

νk,l,d be the random variable denoting the number of values m between m1 and m2 for

◦

◦

which Wm

= (k, l, d); in other words, νk,l,d = |{m : m1 ≤ m ≤ m2 and Wm

= (k, l, d)}|.

◦

√ |Tm,1,1

|

is bounded in probability, and we have Tm2 ,1,1 − T√m1 ,1,1 =

Then E[ν1,1,1 ] = c n √n

◦

◦

m1 − m2 − ν1,1,1 ∼ −|c| n a.a.s., and it follows that Tm

n a.a.s.

0 ,1,1 = Th n,1,1 − (c + o(1))

1

√

H−h

n

◦

◦

◦

Thus, if ηn = √n1 , then TH,1,1 = Th1 n,1,1 − (ηn + o(1)) n. Since TH,1,1

= 0 by the

√

d

◦

definition of H, we have ηn = Th◦1 n,1,1 / n + o(1) → U1,1

(h1 ).

◦

When m = h1 n + o(n), we have Tm,k,l = µk,l (h1 )n + o(n) a.a.s. Hence, for these

◦

values of m, P[Wm

= (κ, λ, d)] = aκ,λ,d + o(1), where we define aκ,λ,1 = λµκ,λ (h), and

11

√

aκ,λ,2 = (κ − λ)µκ,λ (h). If m1 and m2 are as above, then νk,l,d = (ηn ak,l,d + o(1)) n a.a.s.

√ d

◦

Hence νk,l,d / n → ak,l,d U1,1

(h). We have

◦

TH,k,l

− Th◦1 n,k,l = −

X

(d)

νκ,λ,d ζk,l (κ, λ),

κ,λ,d

so it follows that

X νκ,λ (d)

Th◦ n,k,l − nµk,l (h1 )

TH,k,l − nµk,l (h)

√

√

√ ζk,l (κ, λ)

= 1

−

n

n

n

κ,λ,d

X

d

(d)

◦

◦

→ Uk,l

(h1 ) −

ak,l,d U1,1

(h1 )ζk,l (κ, λ) =: Uk,l .

κ,λ,d

Again only a finite number of the summands are nonzero, so the sum is well-defined. Since

◦

{Uk,l

}(k,l)∈Λ∗ are jointly normal random variables and {Uk,l }(k,l)∈Λ∗ are linear combinations

◦

of {Uk,l

}(k,l)∈Λ∗ , it follows that also {Uk,l }(k,l)∈Λ∗ are jointly normal random variables.

Finally we tie in the variable Lm , denoting the number of vertices of degree 1 in Gn,m .

Since vm is an isolated vertex in Gn,m−1 and has degree 1 in Gn,m , it contributes an increase

of 1 to Lm . Thus, if wm is an isolated vertex, we have ∆Lm = 2, if wm has degree 1, then

∆Lm = 0, and in all other cases ∆Lm = 1. All in all,

E[∆Lm | Fm−1 ] = 1 +

Tm−1,1,1 − 1 Lm−1

−

n−1

n−1

(16)

and

Tm−1,1,1

Lm−1

−

+ O(1/n).

n

n

Then we should find the correlation between Lm and Tm,k,l . Thus,

E[(∆Lm )2 | Fm−1 ] = 1 + 3

E[∆Lm ∆Tm,k,l | Fm−1 ] = 2

Tm−1,k−1,l−1

Tm−1,k,l

Tm−1,1,1

δk1 δl1 +

−

+ o(1).

n

n

n

(17)

(18)

Hence, it follows from Theorem 1 that Ln,tn converges to some normal variable χ(t), and

that the convergence is joint with the convergence of Ttn,k,l to Uk,l (t). By a repetition of

the above argument, we can extend this to the variables LH as well; thus there is a normal

d

variable χ such that n−1 LH → χ jointly with the convergence of TH,k,l to Uk,l .

We now consider the second phase of the graph process, when the minimum degree is 1.

The following lemma establishes that the finite-dimensional distributions of {Tm,k,l } are

asymptotically normal in this phase.

Lemma 7. Let Λ∗ be a finite subset of Λ. There are functions µk,l (t) and σ(k,l),(k0 ,l0 ) (t),

which are continuous on (hg , h2 ) such that the following holds. For hg < t < h2 , let

{Uk,l (t)}(k,l)∈Λ∗ be jointly normal random variables such that E[Uk,l (t)] = 0 and such that

E[Uk,l (t)Uk0 ,l0 (t)] = σ(k,l),(k0 ,l0 ) (t). If m = btnc, then

Tm,k,l − µk,l (t)n d

√

→ Uk,l (t)

n

jointly for all (k, l) ∈ Λ∗ .

12

Proof. Again we may assume that Λ∗ is on the form {(k, l) ∈ Λ; k ≤ q}. In order to prove

this lemma, we consider the graph process {Gn,m }m≥H ; that is, we consider Gn,H to be the

initial state. Let m0 = m + H − n ln 2. Then the number of steps from Gn,H to G0n,m is

deterministically equal to m − hn. Lemma 6 then asserts that there are random variables χ

d

d

and Uk,l such that n−1/2 (LH − n ln 2) → χ and n−1/2 (TH,k,l − µk,l n) → Uk,l jointly.

We want to show that Tm,k,l converge jointly to jointly normal random variables; however, in this phase the evolution of these variables also depends on the number of vertices

of degree 1, which is why we included the random variable Lm in the analysis. Thus, we

have to find equations analogue to (10) and to (11), (12) and (13), as well as (16), (17) and

(18). There are fewer details to take care of in this case, since the number of steps made in

the process is determined beforehand as m − H. We will therefore be satisfied with showing

that equations analogue to (10–13) and (16–18) exist, without giving their explicit forms.

We now define Vm ∈ Λ to be the random vector denoting the type of component which

vm is contained in; that is, Vm = (κ, λ) if vm lies in a component with κ vertices and λ leaves.

We let Wm ∈ Λ × {1, 2} be as in the proof of the previous lemma: Wm = (κ, λ, d) if wm is

contained in a (κ, λ)-component, and d = 1 if wm is a leaf, and d = 2 otherwise. Then

P[Vm = (κ, λ) | Fm−1 ] =

while

P[Wm = (κ, λ, 1) | Fm−1 ] =

λTm−1,κ,λ

,

Lm

λTm−1,κ,λ − IVm =(κ,λ),deg(vm )=1

n−1

(19)

(20)

and

(κ − λ)Tm−1,κ,λ − IVm =(κ,λ),deg(vm )>1

.

(21)

n−1

Suppose that Vm = (κ, λ) and that Wm = (κ0 , λ0 , d). Then we lose one (κ, λ)-component and

one (κ0 , λ0 )-component, while we gain one (κ+κ0 , λ+λ0 +d−3)-component. The probability

of this event is obtained by multiplying (19) with (20) or (21) depending on the value of d,

and is therefore on the form φ({n−1 Tm−1,κ,λ }κ≤k+k0 ∪ {n−1 Lm }) + o(n−1/2 ). Moreover,

there is only a finite number of choices of (κ, λ) and (κ0 , λ0 , d) which cause ∆Tm,k,l to be

nonzero. Therefore functions fk,l and g(k,l),(k0 ,l0 ) can be found such that

P[Wm = (κ, λ, 2) | Fm−1 ] =

E[∆Tm,κ,λ | Fm−1 ] = fκ,λ ({n−1 Tm−1,k,l }k<κ ∪ {n−1 Lm }) + o(n−1/2 )

(22)

and

E[∆Tm,κ,λ ∆Tm,κ0 ,λ0 | Fm−1 ] = g(κ,λ),(κ0 ,λ0 ) ({n−1 Tm−1,k,l }k<max(κ,κ0 ) ∪ {n−1 Lm }) + o(1).

Then we consider the number of leaves. By definition, vm is always a leaf, while wm has

m −1

degree 1 with probability Ln−1

, so

E[∆Lm | Fm−1 ] = −1 −

and

Lm−1

+ O(1/n)

n

Lm−1

+ 1 + O(1/n).

n

Finally we have to find an expression for E[∆Lm ∆Tm,κ,λ | Fm−1 ]. Clearly the product

∆Lm ∆Tm,κ,λ is nonzero only if ∆Tm,κ,λ is nonzero. If wm is a leaf, then ∆Lm = −2, while

if wm is not a leaf, then ∆Lm = −1. Thus, an expression for E[∆Lm ∆Tm,κ,λ | Fm−1 ] (up

to an error term of o(1)) can be obtained by multiplying each term in (22) with −1 or −2.

E[∆Lm ∆Lm | Fm−1 ] = 3

13

We have one random variable for every element in Λ∗ , in addition to Lm . Let us rename

the random variables Xm,0 , Xm,1 , . . . , Xm,|Λ∗ | such that Xm,0 = Lm and {Xm,k }1≤k≤|Λ∗ | =

{Tm,k,l }(k,l)∈Λ∗ . We write X n,m = [Xn,m,0 , . . . , Xn,m,|Λ∗ | ]0 . Thus, the functions fk,l and

∗

∗

g(k,l),(k0 ,l0 ) are functions from R|Λ |+1 to R and we have to find a set D ⊂ R|Λ |+1 such

that the conditions of Theorem 1 are satisfied. Unlike in Lemma 6, where all the functions

are linear and automatically satisfy a Lipschitz condition, we have to be careful since Lm

appears in the denominator of (19). Thus, to ensure that a Lipschitz condition is satisfied,

we have to choose D such that n−1 Xm,0 = n−1 Lm is bounded away from 0 whenever

p

X n,m ∈ D. By Lemma 5, there is a continuous function b(t) such that n−1 Xm,0 → b(t)

for all t, and such that b(t) > 0 whenever t ∈ (0, h2 ), and b(h2 ) = 0. Then, for every

ε > 0, there is a δ = δ(ε) > 0 such that b(t) > ε whenever t ∈ [h1 , h2 − δ). We then define

Dε = {z = (z0 , . . . , z|Λ∗ | ); z0 > δ(ε), −ε < zk < 1 + ε for 1 ≤ k ≤ |Λ∗ |}. Then X n,m ∈ Dε

a.a.s. whenever t < h2 −ε, and the functions fk,l and g(k,l),(k0 ,l0 ) satisfy a Lipschitz condition

on Dε .

Let ε > 0. From Theorem 1 it follows that there are continuous functions µk,l (t) and

∗

∗

σ(k,l),(k

0 ,l0 ) (t), such that for all t ∈ (h1 , h2 − ε) the following holds. Let {Uk,l (t)}(k,l)∈Λ be

∗

∗

∗

∗

jointly normal random variables with E[Uk,l (t)] = 0 and E[Uk,l (t)Uk0 ,l0 (t)] = σ(k,l),(k

0 ,l0 ) (t).

Then

Tm0 ,k,l − µk,l (t)n d ∗

√

→ Uk,l (t).

n

We let ε → 0, and see that the convergence holds for all t ∈ (h1 , h2 ).

The only thing that remains is to exchange m0 with m. Let m1 = min(m, m0 ) and

m2 = max(m, m0 ), and let ν(κ,λ),(κ0 ,λ0 ,d)√= |{m : m1 ≤ m ≤ m2 and Vm = (κ, λ) and Wm =

(κ0 , λ0 , d)}|. Assume that m2 − m1 = c n. Since Tm,k,l = µk,l (t)n + o(n) a.a.s. for m1 ≤

m ≤ m2 , we see from (19–21) that a.a.s.

ν(κ,λ),(κ0 ,λ0 ,1) = cλ

√

√

√

√

µκ,λ (t) 0

λ µκ0 ,λ0 (t) n + o( n) =: cr(k,l),(k0 ,l0 ,1) n + o( n)

β1 (t)

and

ν(κ,λ),(κ0 ,λ0 ,2) = cλ

√

√

√

√

µκ,λ (t) 0

(κ − λ0 )µκ0 ,λ0 (t) n + o( n) =: cr(k,l),(k0 ,l0 ,2) n + o( n).

β1 (t)

(d)

Define ζk,l (κ, λ, κ0 λ0 ) to be the value of ∆Tk,l,m in the event that Vm = (κ, λ) and Wm =

(d)

(κ0 , λ0 , d). Then ζk,l (κ, λ, κ0 , λ0 ) is well-defined and equal to an integer between −2 and 1,

inclusive, and

X

X

(d)

(d)

Tm0 ,k,l − Tm,k,l =

ν(κ,λ),(κ0 ,λ0 ,d) ζk,l (κ, λ, κ0 , λ0 ) =

ηr(κ,λ),(κ0 ,λ0 ,d) ζk,l (κ, λ, κ0 , λ0 ),

κ,λ,κ0 ,λ0 d

κ,λ,κ0 ,λ0 ,d

d

√

where η is the random variable found in Lemma 6, such that H−hn

→ η. We know that η is

n

∗

jointly normal with Uk,l for (k, l) ∈ Λ. By Theorem 1, Uk,l (t) are jointly normal with Uk,l ,

so we actually have

X

Tm,k,l − nµk,l (t)

Tm0 ,k,l − nµk,l (t)

(d)

√

√

=

+

ηr(κ,λ),(κ0 ,λ0 ,d) ζk,l (κ, λ, κ0 , λ0 )

n

n

0

0

κ,λ,κ ,λ ,d

d

→

∗

Uk,l

(t)

+ ηsk,l =: Uk,l (t),

∗

where sk,l is a constant for all (k, l) ∈ Λ. Since η and Uk,l

(t) are jointly normal random

variables, the linear combinations are also jointly normal, which completes the proof.

14

4.2

Exponential bound

In order to show that the expectation and variance of Tm,k,l are exponentially bounded, we

will use a branching process argument. In [8] a branching process was introduced in order to

approximate the manner in which one might expose the components of the graph. We will

first need some results from the theory of branching processes. An ordinary Galton–Watson

branching process starts with a single particle. At every step every particle still alive gets

a number of children which is distributed as a random variable Z, and then dies. The size

of the Galton–Watson process is the total number of particles produced by the branching

process. This value may be finite or infinite; if it is finite we say that the branching process

dies out, and the probability that this happens is called the extinction probability of the

branching process.

The following theorem summarizes several facts about branching processes, regarding the

extinction probability and the generating functions associated with the branching process.

It is a combination of results from Chapter I of Athreya and Ney [1] and Theorem VI.6 of

Flajolet and Sedgewick [6].

Theorem 8. Let

P Z be a nonnegative integer-valued random variable. Let pk = P[Z = k]

and let p(z) = k≥0 pk z k be the probability generating function of Z. Let S be the random

variable denoting the size of the Galton–Watson process, where the number P

of offspring of

a given particle is distributed according to Z. Let sk = P[S = k] and s(z) = 0≤k<∞ sk z k .

Let q denote the smallest positive solution to the equation p(z) = z, let τ satisfy

p(τ ) − τ p0 (τ ) = 0,

and let ρ = τ /p(τ ). Then

P[S < ∞] = q,

s(z) is given implicitly by s(z) = zp(s(z)) and sk ∼ ck −3/2 ρ−k , for a constant c.

We now present the branching process from [8]. In order to define the branching process,

we colour the edges in the graph. For d ≥ 1, we let Hd be the smallest value of m such that

the minimum degree of Gn,m is at least d; thus H1 = H. We let all the edges in Gn,H1 be

coloured red, and if m ≤ H2 , we colour the edges in Gn,m \ Gn,H blue. If m > H2 , the edges

in Gn,m \ Gn,H2 do not receive a colour; we will, however, consider the graph process when

m ≤ H2 , so that all edges are coloured. When m ≤ H1 , a step in the graph process consists

of attaching an isolated vertex to another vertex; thus, no cycle can be formed in this phase,

and so Gn,m contains no red cycle. When m > H1 , any vertex of degree 1 must necessarily

be incident to a red edge, and is therefore not incident to any blue edges; when m ≤ H2 , a

step consists of attaching such a vertex to another vertex, and no blue cycle can therefore

be formed either. Thus, when H1 < m ≤ H2 , the graph Gn,m is a union of a red and a blue

forest. Moreover, whenever a blue tree grows with one vertex, the new vertex must have

degree 1 and be incident to one red edge; hence, the only way a vertex incident to more

than one red edge can become part of a blue tree is if at some stage in the graph proces an

edge vm wm is added such that neither vm nor wm is incident to a blue edge in Gn,m−1 , and

wm has degree larger than 1. Hence, every blue tree contains at most one vertex incident

to more than one red edge. We call a vertex light if it is incident to exactly one red edge,

and heavy if it is incident to more than one red edge.

For a vertex v, let Cred (v) and Cblue (v) be the maximal red and blue tree, respectively,

incident to v. Let k and l be positive integers. In [8] the asymptotic probability that Cred (v),

respectively Cblue (v), consists of exactly k vertices of which exactly l are light, is calculated.

15

To be more precise, there are constants Px,y,k,l such that a.a.s.

P[Cx (v) is of type (k, l) | v is y] = (1 + o(1))Px,y,k,l ,

(23)

where x is ‘red’ or ‘blue’ and y is ‘light’ or ‘heavy’. Since (23) holds a.a.s., we can in the

following condition on the event that it holds.

Moreover, it is observed that the order and number of light vertices in Cred (v) is essentially independent of the order and number of light vertices in Cblue (v), when we condition

on whether v itself is light or heavy. What this means is that if we know whether v is light

or heavy, then (23) holds for Cred (v), even if we condition on the type of Cblue (v), and vice

versa.

We let Gn,m be an instance of the graph process such that (23) holds. We let πx,y,k,l =

P[Cx (v) is of type (k, l) | v is y], where v is a randomly selected vertex. Then πx,y,k,l =

(1 + o(1))Px,y,k,l .

We now define a multitype branching process mimicking the graph process in the following way. We start with a randomly chosen vertex v, which may be light or heavy, and

generate a red tree incident to it, whose type is chosen at random according to the probabilities πx,y,k,l . By ‘type’ we mean the number of vertices and the number of light vertices. At

every vertex in this red tree we add a blue tree, again with probabilities πx,y,k,l . At any new

vertex generated this time, we add a red tree, and we continue in this manner, alternatingly

generating red and blue trees. Since a vertex is not necessarily incident to a blue edge, it is

possible that no new vertices are generated when a blue tree is to be added; thus, there is

a chance that the branching process dies out. On the other hand, every vertex is incident

to at least one red edge, so every time a red tree is to be added, at least one new vertex is

generated. It was found in [8] that the probability that v is in a component of order O(log n)

is asymptotically equal to the probability that this branching process dies out, which is 1

when t < hg and less than 1 when t > hg .

The branching process above is a multitype branching process: a vertex in the process

may either be light or heavy, and it can be generated either when a red tree or a blue tree

is created. We give the vertices colour as well, and say that a vertex is red (blue) if it

was created when a red (blue) tree was generated. For our purposes, it is easier to work

with an ordinary branching process with only one type of vertices. We therefore consider

a variant of this branching process, where we are only interested in one of the types of

vertices, say the light, red vertices. Whenever we make a step in the branching process and

acquire some vertices which are not light, red vertices, we continue the branching process

from these vertices, until we only have light, red vertices. Then we get a Galton–Watson

process. Let Z be the random variable denoting

of red light vertices generated

P the number

from one red light vertex, and let pZ (z) =

P[Z = k]z k be the corresponding probability

generating function. Since the original multitype branching process is supercritical, this

Galton–Watson process must also be supercritical, so EZ > 1.

We will now use Theorem 8. The number of vertices created in one step is finite with

0

0

probability 1, so p(1) = 1, while

Pp (1) = EZ > 1. Let f (z) = p(z) − zp (z), so that

f 0 (z) = −zp00 (z). Since zp00 (z) = k≥0 k(k − 1)pk z k−1 , and pk > 0 for some k ≥ 2, we have

f 0 (z) < 0 for all z > 0. Since f (0) = p(0) = p0 > 0 and f (1) = p(1)−p0 (1) < 0, we must have

0 < τ < 1; then f (z) > 0 for z ∈ (0, τ ) and f (z) < 0 for z ∈ (τ, 1). Let now r(z) = z/p(z).

Then, r0 (z) = f (z)/p(z)2 , so r(z) is increasing on (0, τ ) and decreasing on (τ, 1). Moreover,

r(0) = 0 and r(1) = 1, so ρ = r(τ ) > 1. Then, by Theorem 8, P[S = k] ∼ ck −3/2 ρ−k for a

constant c.

The conclusion is that, conditioned on the branching process dying out, the number of

light, red vertices is exponentially bounded. By the same argument one can show that the

16

number of heavy, red vertices is exponentially bounded. Since every vertex is adjacent to at

least one red edge, a blue vertex always generates at least one red vertex, and so the total

number of vertices is at most twice the number of red vertices generated. Hence, the number

of vertices generated by the multitype branching process is also exponentially bounded, and

since the probabilities πx,y,k,l were given by the actual structure of Gn,m , this holds also

for the components in the real graph process; in other words, if C(v) is the component

containing the vertex v,

ETm,k,l ≤ nP[|C(v)| = k] ≤ Knρ0k ,

for some constants K > 0 and 0 < ρ0 < 1.

Let T be an arbitrary tree on k vertices, whose edges are ordered and coloured red

and blue such that a edges are coloured red and b edges are coloured blue, where a +

b = k − 1, and such that all red edges appear before the blue edges in the ordering. Let

v1 w1 , v2 w2 , . . . , vm wm be the m edges added in the graph process, such that vi is first and

wi the second vertex chosen at every step. Let A be the event that exactly a vertices among

v1 , . . . , vH belong to A, and exactly b vertices among vH+1 , . . . , vm belong to A. Let us

assume that A holds, and let vi1 , . . . , vik−1 be the k−1 vertices chosen in A. Let xj ∈ {0, 1, 2}

be the number of vertices in {vij , wij } having minimum degree in Gn,ij −1 . Let yj be the

number of vertices of minimum degree in A. Let X = x1 · · · xk−1 and Y = y1 · · · yk−1 .

Conditioned on A, the probability that A forms a tree isomorphic to T preserving the edge

colouring, and such that the order in which the edges are added in the process matches the

ordering of the edges in T is equal to

xk−1 1

x1 1

···

y1 n − 1

yk−1 n − 1

n−k−1

n−1

m−k+1

=

X

Y

1−

k

n−1

m

(n − k − 1)1−k (24)

To see that this equation is correct, note that for the “correct” edge relative to T to be added

at the next step, one of the endpoints must be chosen as the first vertex. If we condition on

that vertex belonging to A, the probability that the vertex is one of the endpoints of that

edge is 2/yj if both endpoints have minimum degree, 1/yj if only one of the endpoints has

minimum degree, and 0 if none of the endpoints has minimum degree. The probability that

wij is the other endpoint of the graph is then 1/(n − 1). The last factor is the probability

that the remaining m − k + 1 edges in the graph lie completely outside of A.

Assume instead that A is a set of k vertices in Gn−k,m−k+1 . (The reason for this will be

explained below). Conditioned on A, the probability that A forms a tree isomorphic to T

becomes

m−2k+2

x1

1

x2

1

xk−1

1

n − 2k − 1

·

· ··· ·

y1 n − k − 1 y2 n − k − 1

yk−1 n − k − 1

n−k−1

m−k+1

X

k

=

1−

(n − 2k + 1)1−k

Y

n−k−1

which differs from (24) by a factor of (1 + O(k 2 /n)).

Let B be the event that A forms a tree of any kind in Gn,m . If B holds, there are

k − 1 edges inside A and no edges between A and V \ A, where V is the entire vertex set.

Thus, if we condition on B, the graph process Gn,m restricted to V \ A is identical to the

process Gn−k,m−k+1 . From this it follows that the expected number of pairs of trees of

type (k, l) is

E[Tm,k,l (Tm,k,l − 1)] = P[Cv = k]2 (1 + O(k 2 /n))n2 .

17

Hence

2

E[Var Tm,k,l ] = E[Tm,k,l

] − E[Tm,k,l ]2 = E[Tm,k,l (Tm,k,l − 1)] − E[Tm,k,l ]2 + E[Tm,k,l ]

= P[C(v) = k]2 (1 + O(k 2 /n))n2 − P[C(v) = k]2 n2 + nP[C(v) = k]

= O(k 2 n)P[C(v) = k]2 + nP[C(v) = k] ≤ K 00 nρ00k

for some constants K 00 and ρ00 with 0 < ρ00 < 1.

4.3

Small cyclic components

To complete the proof of Theorem 4, we have to show that the expected number of vertices

√

(n)

in cyclic components is o( n). Recall that Cm is the random variable denoting the number

of such vertices in Gn,m .

Let k− = B ln n for some constant B and let k+ = n1−ε for some ε with 0 < ε < 1/2. Let

A be the event that there is either a component in Gn,m with between k− and k+ vertices or

more than one component with at least k+ vertices. In [8] it is shown that PA = o(1); this

bound was made just as strong as was necessary to prove the main theorem of [8]. However,

it is immediate from the calculations in [8] that the probability can be made much smaller,

so for large enough B, we have, say, PA = o(n−1 ).

Let us call a component small if it has at most k− vertices. Let v and w be the two vertices

chosen at one stage in the graph process. The probability that v and w both belong to the

same component, having at most k− vertices, is bounded by k− /n. The expected number

of edges added in the graph process, such that both endpoints belong to the same small

component is therefore mk− /n. Thus, the expected number of vertices in small unicyclic

2

/n = O(ln2 n).

components is at most mk−

Since Cn,m clearly is at most n, we have

E[Cn,m ] = E[Cn,m | A]P[A] + E[Cn,m | A]P[A]

≤ O(ln2 n) + n · o(n−1 ) = O(ln2 n).

5

Other random graph processes

The previous section considered in detail the minimum-degree graph process, and used the

method explained in Section 3 to show that the giant component is asymptotically normally

distributed. The argument for this process is more complicated than it would be for several

other graph process it is natural to study, because of the “discontinuity” in the evolution of

the graph when the minimum degree increases from 0 to 1.

The most “important” necessary condition for this method to be applied is that the

differential equation method can be applied. The other conditions (the exponential bound

and the small cyclic components) are likely to hold in most typical random graph processes,

although they may be difficult to verify in some cases.

In the d-process, which is studied by Ruciński and Wormald [11, 12], a new edge is added

to the graph uniformly at random under the provision that the maximum degree remain at

most d. Suppose C is a component at some stage in the d-process. Then the probability that

the next edge to be added is incident to some vertex in C is proportional to the number of

vertices in C with degree strictly less than d. Thus, we need to keep track of the number of

vertices of degree d in every component. But this means that we also have to keep track of all

the other possible degrees. Thus, the classes of trees must be defined in terms of the entire

18

degree sequence, so we have {Tk,πk }k,πk , where πk is a partition of k. Although the number

of classes seems to be very large, perhaps making the actual computations prohibitive, the

number of classes of trees with k vertices is clearly O(k d ), so Theorem 2 can be applied.

To the author’s knowledge it has not been proven that there actually exist a phase

transition and a giant component in the d-process; however, since the evolution mechanism

is similar to the one in the standard GER

n,m model, one may reasonably conjecture that

there are, and from the above arguments it also seems safe to conjecture that whenever

there is a linear-sized giant component in the d-process, its order is asymptotically normally

distributed.

We also mention the Achlioptas process, which is studied by Spencer and Wormald [15].

In the general Achlioptas process, at every stage one is presented with two randomly chosen

edges, and one has to choose one of them to add to the graph, seeking either to promote

or delay the formation of a giant component. The problem is to find an optimal strategy

to either make sure that the giant component is formed as soon as possible, or as late

as possible. Our method probably does not work for the general problem, as it is likely

that there are strategies which actively prevent the giant component from being normally

distributed. However, Spencer and Wormald [15] suggest strategies where the decision about

which edge to pick depends solely on the orders of the components containing the endpoints

of the edges. This situation is ideal for the differential equation method. It is shown in [15]

that such processes exhibit a phase transition and a giant component. The point of the phase

transition depends, of course, on the exact strategy which is used; however, apart from that

the giant component behaves as in most other typical random graph processes, and with

the method in the present paper, it ought to be possible to show that it is asymptotically

normally distributed.

6

Proof of Theorem 1

Theorem 1 is a generalization of the main theorem in Seierstad [13]. The difference lies

in that we allow X 0 to be non-deterministic, provided that it converges to a multivariate

normal distribution; that is

X 0 − nµ0 d

√

→ N (0, Σ0 ).

(25)

n

√

In [13] X 0 has to be deterministic, or at least have deviations at most o( n) (although

this is unfortunately not stated very precisely in [13]). In this section we will show that

the theorem still holds when (25) is satisfied. We will not include every step in the proof

rigorously, as it is in large parts similar to the proof in [13], but will be content with including

the main steps in the argument which differ from the previous version. The proof is based

on a central limit theorem for near-martingales by McLeish [9]; the following is similar to

the version of that theorem which was proved in [13], except that we allow the inital state

to be nondeterministic.

Theorem 9. Let (Ωn , Fn , Pn ) be a sequence of probability spaces, and assume that a filtration Fn,0 ⊆ Fn,1 ⊆ · · · ⊆ Fn,mn ⊆ Fn is given. For n ≥ 1 and 0 ≤ m ≤ mn , let S n,m be an

Fn,m -measurable q-dimensional array of random variables, and let Σ0 and Σ∗ be symmetric

d

q × q-matrices. Suppose that S n,0 → N (0, Σ0 ). Assume that the following conditions are

satisfied.

(i) maxm k∆S n,m k has uniformly bounded second moment.

p

(ii) maxm k∆S n,m k → 0.

19

Pmn

p

(∆S n,m )2 → Σ∗ .

(iii) For all 1 ≤ i, j ≤ q, m=1

Pmn

p

(iv)

m=1 E[∆S n,m | Fm−1 ] → 0.

Pmn

2 p

(v)

m=1 E[∆S n,m | Fm−1 ] → 0.

d

Then S n,mn → N (0, Σ), where Σ = Σ0 + Σ∗ . Moreover, S n,0 and S n,m converge jointly.

Pm

Proof. Let S ∗n,m = S n,m − S n,0 = k=1 ∆S n,k . Then S ∗n,m has deterministic initial state.

d

By Theorem 3 in [13], if we condition on F0 , then S ∗n,m → N (0, Σ∗ ).

Assume first that q = 1, and let σ02 and σ ∗ 2 be the sole entries in Σ0 and Σ∗ , respectively.

∗

2 ∗2

Then the above can be expressed as E[eitS n,mn | F0 ] → e−t σ /2 for every t, where i is the

imaginary unit. Let a and b be arbitrary real numbers, and define T n = aS n,0 + bS n,mn .

Then, since Sn,0 is Fn,0 -measurable,

∗

∗

E[eitT n ] = E[eit(aS n,0 +bS n,m ) ] = E[eitaS n,0 E[eitbS n,m | F0 ]] → e−t

2

(a2 σ02 +b2 σ ∗ 2 )

.

Thus, S n,0 and S ∗n,mn tend jointly to jointly normal random variables, and in particular

d

S n,mn = S n,0 + S ∗n,mn → N (0, σ02 + σ ∗ 2 ). If q > 1, the theorem follows from the univariate

version by the same proof as that of Theorem 3 in [13].

We are now ready to prove Theorem 1. Let C = n−1/2 (X 0 − nµ0 ), and define X m =

√

d

X m − C n. By assumption C → N (0, Σ0 ) and X 0 = nµ0 , so X 0 is deterministic. Let

αm = α(m/n) and let Y m = X m − nαm . Clearly, ∆X m = ∆X m , so

E[∆X m | Fm−1 ] = F (n−1 X m−1 ) + o(n−1/2 )

= F (n−1 X m−1 + n−1/2 C) + o(n−1/2 )

= F (αm−1 + n−1 Y m−1 + n−1/2 C) + o(n−1/2 ).

Recall the definitions of J and T from Section 2. We let Tm = T (m/n), Am = J(αm ) and

Um = I − n−1 Am . Then (Lemma 1 in [13])

Tm = Tm−1 Um−1 + O(n−2 ),

so that

∆Tm = Tm−1 (Um−1 − I) = n−1 Tm−1 Am−1 .

(26)

q

Finally we define Z m = Tm Y m . We know from calculus that if a, y ∈ R , then

F (a + y) − F (a) = JF (a)y + O(kyk2 )

as y → 0. Thus

E[Um−1 Y m − Y m−1 | Fm−1 ]

= Um−1 (E[X m | Fm−1 ] − nαm ) − X m−1 + nαm−1

= (I − n−1 Am−1 )(X m−1 + F (αm−1 + n−1 Y m + n−1/2 C)

− nαm−1 − F (αm−1 )) − X m−1 + nαm−1 + o(n−1/2 )

= − n−1 Am−1 Y m−1 + JF (αm−1 )(n−1 Y m−1 + n−1/2 C) + o(n−1/2 )

= n−1/2 Am−1 C + o(n−1/2 ).

20

Hence

E[∆Z m | Fm−1 ] = E[Tm Y m − Tm−1 Y m−1 | Fm−1 ]

= Tm−1 (E[Um−1 Y m | Fm−1 ] − Y m−1 ) + O(n−2 )

= n−1/2 Tm−1 Am−1 C + o(n−1/2 ).

(27)

Let Ξ∗ (t) = Ξ(t) − Σ0 . Then Ξ∗ (t) is a solution of the integral in (3), satisfying Ξ∗ (0) = 0.

One can verify that

m

X

p

−1

n

(∆Z k )2 → Ξ∗ (m/n).

k=1

The rather lengthy calculations needed to prove this are identical to those in the proof of

Lemma 3 in [13]. Also similarly to [13], one can show that ∆Z m = O(β) and (∆Z m )2 =

O(β 2 ) a.s. We now define M m = n−1/2 Z m + Tm C. We will show that M m is almost a

d

martingale, in the sense that it satisfies the conditions of Theorem 9. We have M 0 = C →

N (0, Σ0 ) by assumption. It is easy to see that (i) and (ii) are satisfied. For (iii) we obtain

m

X

(∆M k )2 =

k=1

m

X

(n−1/2 ∆Z k + ∆Tk C)2

k=1

n−1

=

m

X

!

(∆Z k )2

p

+ o(1) → Ξ∗ (m/n).

k=1

For (iv), we find that

m

X

m

X

E[∆M k | Fm−1 ] =

k=1

(26,27)

=

k=1

m

X

E[n−1/2 ∆Z k + ∆Tk C | Fm−1 ]

n−1 Tm−1 Am−1 C − n−1 Tm−1 Am−1 C + o(n−1 )

k=1

= m · o(n−1 ) = o(1).

d

For (v) the calculations are similar. It now follows from Theorem 9 that M m → N (0, Ξ(t)),

which means that

Tm (X m − nαm )

d

√

+ Tm C → N (0, Ξ(t)).

n

Thus

√

Tm (X m − nαm )

Tm (X m − nαm + C n) d

√

√

=

→ N (0, Ξ(t)),

n

n

so

X m − nαm d

√

→ N (0, Σ(t)),

n

where Σ(t) = T (t)−1 Ξ(t)(T (t)0 )−1 .

References

[1] K. B. Athreya and P. E. Ney. Branching processes. Springer-Verlag, New York, 1972.

Die Grundlehren der mathematischen Wissenschaften, Band 196.

21

[2] D. Barraez, S. Boucheron, and W. Fernandez de la Vega. On the fluctuations of the

giant component. Combin. Probab. Comput., 9(4):287–304, 2000.

[3] M. Behrisch, A. Coja-Oghlan, and M. Kang. The order of the giant component of

random hypergraphs. submitted.

[4] P. Billingsley. Convergence of probability measures. Wiley Series in Probability and

Statistics: Probability and Statistics. John Wiley & Sons Inc., New York, second edition, 1999.

[5] P. Erdős and A. Rényi. On the evolution of random graphs. Magyar Tud. Akad. Mat.

Kutató Int. Közl., 5:17–61, 1960.

[6] P. Flajolet and R. Sedgewick. Analytic combinatorics. Web edition (available from the

authors’ web sites). To be published in 2008 by Cambridge University Press.

[7] M. Kang, Y. Koh, S. Ree, and T. Luczak. The connectivity threshold for the min-degree

random graph process. Random Structures Algorithms, 29(1):105–120, 2006.

[8] M. Kang and T. G. Seierstad. Phase transition of the minimum degree random multigraph process. Random Structures Algorithms, 31(3):330–353, 2007.

[9] D. L. McLeish. Dependent central limit theorems and invariance principles. Ann.

Probability, 2:620–628, 1974.

[10] B. Pittel. On tree census and the giant component in sparse random graphs. Random

Structures Algorithms, 1(3):311–342, 1990.

[11] A. Ruciński and N. C. Wormald. Random graph processes with degree restrictions.

Comb. Probab. Comput., 1(2):169–180, 1992.

[12] A. Ruciński and N. C. Wormald. Connectedness of graphs generated by a random

d-process. J. Aust. Math. Soc., 72(1):67–85, 2002.

[13] T. G. Seierstad. A central limit theorem via differential equations. To appear in Ann.

Appl. Probab., available from the journal’s website.

[14] T. G. Seierstad. The phase transition in random graphs and random graph processes.

PhD thesis, Humboldt University Berlin, 2007.

[15] J. Spencer and N. C. Wormald. Birth control for giants. Combinatorica, 27(5):587–628,

2007.

[16] V. E. Stepanov. On the probability of the connectedness of a random graph Gm (t).

Theor. Probability Appl., 15:55–67, 1970.

[17] N. C. Wormald. Differential equations for random processes and random graphs. Ann.

Appl. Probab., 5(4):1217–1235, 1995.

[18] N. C. Wormald. The differential equation method for random graph processes and

greedy algorithms. In M. Karoński and H-J. Prömel, editor, Lectures on approximation

and randomized algorithms., pages 75–152. PWN, Warsaw, 1999.

22