Gaining Ground Information Database

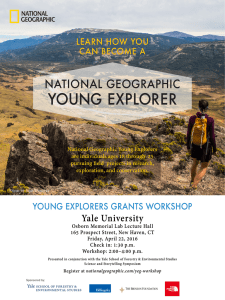

advertisement