Other Voices, Other Ways, Better Practices Bridging Local and Professional Environmental Knowledge

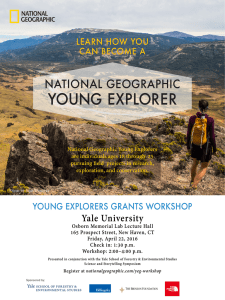

advertisement