P T E &

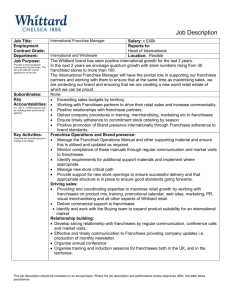

advertisement