Document 11495671

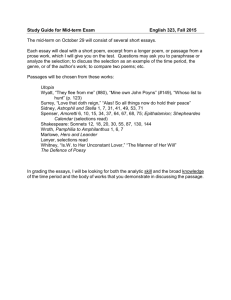

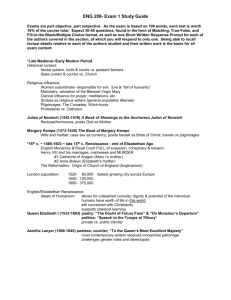

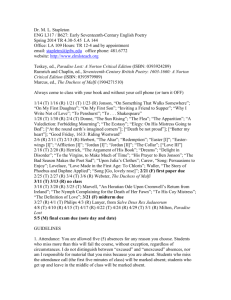

advertisement