Document 11495670

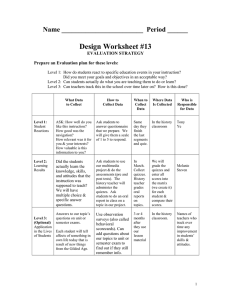

advertisement