Assessment of Students’ Reading Practices in Chabot’s Developmental English Classes

advertisement

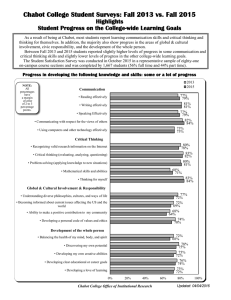

Assessment of Students’ Reading Practices in Chabot’s Developmental English Classes Report Prepared by Katie Hern With extensive support from Jamie Chandler, Program Assistant, Faculty Inquiry Network May 18, 2010 Description of Assessment Tool The Metacognitive Awareness of Reading Strategies Inventory (MARSI) was developed by educational researchers Mokhtari and Reichard (2002). This survey lists 30 different strategies readers use to make sense of texts, and it asks students to rate the frequency with which they use these strategies in academic reading, along a 5-point scale from 1 (Never) to 5 (Always). Student responses are grouped into average scores for three areas – Global Reading Strategies, Support Reading Strategies, and Problem-Solving Strategies, along with an overall score. The scoring scale: High = 3.5 and up, Medium = 2.5-3.4, Low = 2.4 and below. Sample: We administered this survey in 5 sections of Chabot’s English 102: Reading, Reasoning, and Writing (Accelerated), as part of the Jumpstart Initiative targeting first-time college students who enrolled at Chabot in the late summer 2009 (Instructors: Chowenhill, Hern, Johnston, Klevens, Magallon). Students completed the survey during the first week of Fall 2009, and then completed it again during the last two weeks of the semester. Their pre- and post-class responses were compared as a way to assess the degree to which instruction was influencing students’ reading practices. Student Learning Outcomes Assessed By the end of English 102, students should be able to: 1. use pre-reading techniques to facilitate understanding of texts, including access background knowledge in the subject area; establish own purpose for reading the material; assess the difficulty of the text, including vocabulary, sentence structure, and concepts and make a plan for approaching it; establish outcomes for the reading material prior to reading, for instance, forming appropriate questions and using structural cues about how the textbook or essay is organized; 2. take charge of reading, applying strategies to unlock the meaning from texts, including identifying passages that are causing difficulty to comprehension; developing strategies to work through difficult passages; identifying and correcting reading miscues; understanding such text features as structure, transitions, captions, graphs, charts; 3. read actively and critically, and effectively use textual annotation; What We’ve Learned English Departmental Level The responses from this sample gave us new information about the reading practices of incoming, first-time college students – what kinds of things do they say they do and don’t do regularly when they read academic texts. This helps us have a starting picture of them as readers and ideas about what we might want to emphasize in our instruction; for example, which of the “low” usage might we want to be intentional about helping students cultivate? One important trend we saw across all five sections is that students report the lowest usage of the category of "support reading strategies": I take notes while reading to help me understand what I read. When text becomes difficult, I read aloud to help me understand what I read I summarize what I read to reflect on important information in the text. I discuss what I read with others to check my understanding I underline or circle information in the text to help me remember it I use reference materials such as dictionaries to help me understand what I read. I paraphrase (restate ideas in my own words) to better understand what I read. I go back and forth in the text to find relationships among ideas in it. I ask myself questions I like to have answered in the text. Because these strategies are important to being an active reader – and because they aid significantly in understanding complex texts – these are promising areas for attention in English classrooms. We also found evidence that instruction in the 5 sample English 102 sections was positively impacting students’ reading practices. In 4 out of the 5 sections sampled, students’ overall average moved from the medium range to the high range, and there were particularly strong gains in support reading strategies. Individual Faculty Level Each faculty member was able to see how students’ use of the 30 specific reading strategies changed over the semester. In many cases, this provided positive validation of reading instruction, with students reporting increased usage of key reading practices that instructors had emphasized in class. For example, Katie Hern saw that for many of the reading practices she emphasized as routines in her classroom, average scores for the class increased significantly: “I critically analyze and evaluate the information presented in the text” Starting average: 2.73 (medium) Ending average: 3.57 (high) “I summarize what I read to reflect on important information in the text.” Starting average: 2.93 (medium) Ending average: 3.78 (high) “I discuss what I read with others to check my understanding.” Starting average: 2.66 (medium) Ending average: 3.52 (high) The results also helped each instructor identify areas for future attention in their classes. For example, Hern found that for certain important reading practices, average student responses changed very little, and she plans to be more intentional about cultivating these practices among future students. “I take notes while reading to help me understand what I read.” Starting average: 2.64 (medium) Ending average: 2.89 (medium) “I preview the text to see what it’s about before reading it.” Starting average: 3.06 (medium) Ending average: 3.31 (medium) “I go back and forth in the text to find relationships among ideas in it.” Starting average: 3.03 (medium) Ending average: 3.27 (medium) Individual faculty reflections from Klevens, Chowenhill, and Magallón are available in separate reports on Chabot’s Center for Teaching and Learning website. A Note about the Tool: For students with severe reading difficulties, the MARSI survey may not be a good assessment instrument. In a few cases, instructors’ individual interactions with students and students’ performance on other reading assessments (e.g. tests of reading comprehension, annotations, think alouds) revealed significant reading problems that their survey responses did not.