Reading Apprenticeship Marianna Matthews English 4 Spring 2011

advertisement

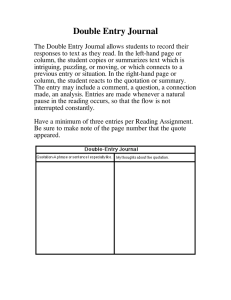

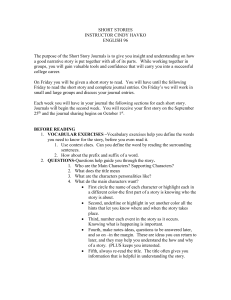

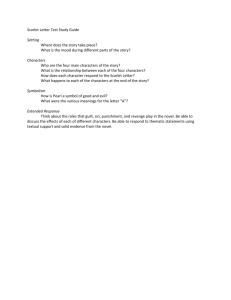

Reading Apprenticeship Marianna Matthews English 4 Spring 2011 At the beginning of the semester, I told Ss I had taken a professional development workshop called Reading Apprenticeship and I would be experimenting with some of the techniques I’d learned to help student improve their reading, particularly reading English literature. I explained that this was experimental. I’d never used some of these techniques as formal, required part of the course work before, and I would be asking for feedback along the way. Using the opening paragraph of “The Garden Party” by Katherine Mansfield on the document camera, I demonstrated “Talking to the Text.” After demonstrating using the first few sentences, I asked students to partner up and continue with the paragraph, one students thinking aloud and the other student keeping notes. This failed—I was mixing two exercises, hadn’t given them adequate instruction, probably hadn’t demonstrated what I was aiming for well enough, etc. I failed to do any kind of a reading strategy inventory—so they didn’t know what I was trying to get them to do—be aware of how they get information from a text. I put the paragraph back on the overhead and changed the focus—individual students read sentence by sentence and I asked the class what this sentence told them about the setting. This was more successful, but was not making students aware of their own reading strategies—which I think was my goal. ___________________________ A second technique I’d decided to use was the reading Log or Reading Journal. I asked students to keep a Reading Journal for all of their homework reading assignments: short stories, novel, poetry, & drama. I distributed a template for the reading Journal pages, but told students they could adapt it to suit their own needs but that the important thing was to use the journal in some form every time they read. The pattern would be to read the assignment with the journal alongside for homework and then in class, students would have 10-15 minutes to discuss among themselves their questions and comments on the text. Then share perhaps one comment per group with the whole class. In this way, I hoped to create a learning environment in which students could bond with each other and feel safe. The third or fourth week of the semester, after reading three short stories, I conducted an informal, anonymous survey. I asked: How is the Reading Journal working out? Is it helping your reading? Is it helping your understanding? Twenty-five students responded: 3 wrote that is was distracting, they didn’t like interrupting the flow to write things down. 4 wrote they’d adapted the journal, preferring to write on post its or annotating directly in the book 18 wrote that it was helping with their reading & understanding, helping them stay focused, helping with discussion, gave them “more depth,” and that it was useful writing down the exact quote and page number. I considered this a success. Students were using a tool, improving their reading & understanding and they were aware of the benefit. After reading the fifth and final short story, I did a spot check on sharing/discussion day and found only a handful of students had used the journal (some continued to use post its). So . . . mixed result. I assume once I asked for feedback, they thought the pressure was off. Since this was a second year English course, I didn’t feel it was necessary to collect the journals and do a point tabulation. But maybe that was necessary. My inquiry question was: Will using reading journals lead students to deepen their thinking and understanding of a literature text by providing a safe place not only for questioning but also reflection? Will students progress from awareness of their reading to the point where they can begin subject matter discourse in the journals? I collected two journal sets (template attached) from the students: one from the second short story we read: 2/2 (third week of semester), “The Storm,” focus on symbolism, and one from the final chapters of the novel 3/23 (10th week of semester), The Bean Trees. “The Storm” Students’ comments were fewer than their quotations, that is, the left column almost always had more writing than the right hand column. Ss quoted short passages from the story and didn’t try to summarize or paraphrase on the left side. Ss comments consisted of far more questions than answers. Not surprisingly, students made use of suggested leads on the journal template. Most of the questions dealt with vocabulary (the story was written in 1898 and due to its sexual nature, much of the language is necessarily subtle). Students also asked who was who (character identification), asked what the author meant or translated passages into their own words. These kinds of questions seem to me to be matters of identification or simple comprehension. Some students drew conclusions about symbolism (the story focused on symbolism) reached conclusions about character and theme and a few observed irony of language and the use of dialect to illustrate character. Some commented on figurative language that struck them. These entries seemed to display more than simple comprehension, but went on to make inferences and draw conclusions. A few students commented on character analysis and one or two made connections with outside reading. The Bean Trees Students’ comments were much more extensive. Generally, the right hand column had more writing than the left hand column. The reading assignment was five chapters at the end of a novel rather than one short story, still Ss filled out more than one journal page per chapter. Further, most of the entries on the left side were direct quotes, but there were some summaries/paraphrases. (this seems to indicate greater independence) There were far fewer simple comprehension questions/comments. There were more comments than questions. Although the language of the novel was somewhat regional it was more accessible than the language in “The Storm.” And the students had already read 2/3 of the novel. A few of the entries dealt with comprehension: vocabulary, interpreting what the author meant. Most of the comments reflected dealing with the text in an analytical way: analyzing character, analyzing symbolism, drawing conclusions about the theme, and making predictions. A few entries (more than with the short story) showed the reader making a personal connection with the text and bringing in outside knowledge to inform their understanding. Conclusion: I definitely see development in the students’ ability to extract meaning from a text. By the tenth week, the students demonstrated an ability and willingness to dig deeper in reading and thinking about a literature text. I think keeping the journals contributed to this and not because they were accountable to the teacher, but because it was a tool that, by the simple act of writing something down, contributes to deeper thought. In the future: I will figure out how to do a brainstorm activity of reading strategies so that Ss can become aware of their own skills and we have a common vocabulary. I will emphasize the metacognitive element early and more. I’ll try to know better what I’m doing and use talking to the text, and think alouds early on to make students aware that they do have reading skills; we’re just going to take them out and look at them so they can become aware of them. I will probably alternate collection of the journals so that students will do them. I may make the journals more guided so that students will be directed to focus on certain concepts. Thanks so much for all of your help, Cindy. I don’t know what Chabot is going to do without you! Marianna