BOSTON COLLEGE INTERNATIONAL AND COMPARATIVE LAW REVIEW

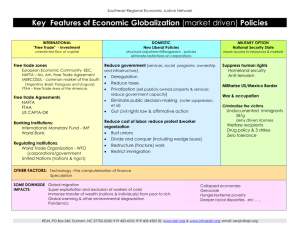

advertisement