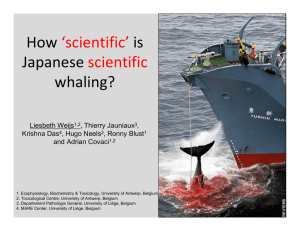

Boston College Environmental Affairs Law Review Volume 36

advertisement