BALANCING ACT: FINDING CONSENSUS ON STANDARDS FOR UNMASKING ANONYMOUS INTERNET SPEAKERS

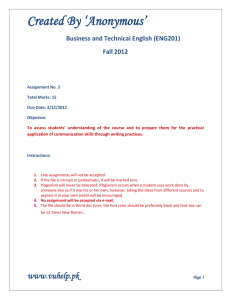

advertisement