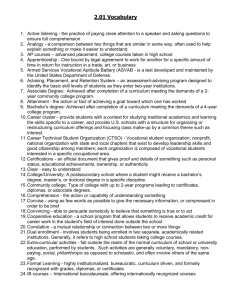

SCHOLASTIC ACHIEVEMENT OF HIGH SCHOOL VOCATIONAL

advertisement