R C :

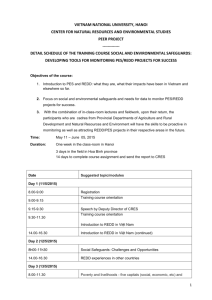

advertisement