for the

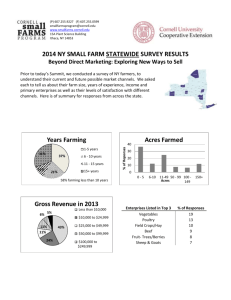

advertisement