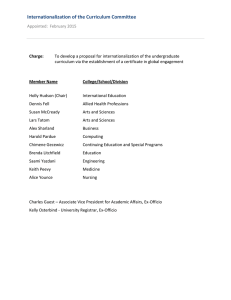

Internationalizing Higher Education Worldwide National Policies and Programs

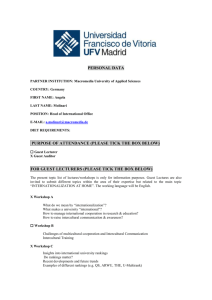

advertisement