THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF RAW MATERIALS AND DEPENDENCE THEORY, GEOPOLITICS REVISITED Helge llveem

advertisement

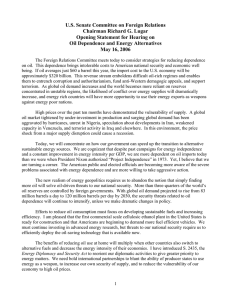

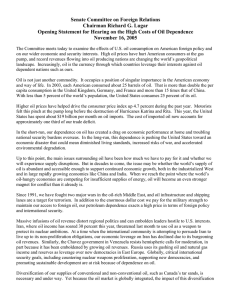

THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF RAW MATERIALS AND DEPENDENCE THEORY, GEOPOLITICS REVISITED Helge llveem International Peace Research Institute, Oslo Paper presented to the XIth International PoliticaZ Science Association Congres , Edinburgh, 16-22 August 1976 The problem The 'resource crisis' no doubt has given increased weight to the spatial dimension of the global political economy. I am referring to the perception of a crisis, not to its 'objective existence', which is disputed. And I am referring to the per- ceptions which are held in the dominant, center economies of the international system. Concern about dependence on foreign supply of natural resources - land, energy, or raw materials - is far from being a new phenomenon. The concern has been found salient enough to (partially) explain why big powers have gone to war, governments have decided to colonize or re-colonize whole subcontinents, and corporations have organized or taken part in the overthrow of locally elected governments which they have seen as a (potential) threat to supply security. Any of such measures as have been taken, or have been contemplated, have been defended on the ground that they were last-resort action against attempts to 'strangulate' the supplied nation (Kissinger 1975) or to maintain an open international market of resources which is seen as a prerequisite to peace (Leith et al., 1943). The concern probably has been particularly manifest in periods of crisis, such as the 1938-45 period, the Korea war and the 1973-75 p e r i o d s . T h i s has led many observers to the conclusion that in such periods the crucial problem has been that the normal functioning of the market has been invaded, in fact upset, by the political system: become 'politicized'. resource flows have It is true that resource markets in the periods referred to have been subject to processes and structures that have largely imposed themselves on the market mechanism. What is hot correct is that this superimposure on the market of the political system is particular, is only true in periods of crisis. Ever since the first empire of some size and duration (at least the Roman) set up external supply lines that made peripheral imperial nations resource areas subordinated to the imperial center, the market has been 'rigged' by politics. It is an ahistorical, often superficial and at . times perhaps 'structure-blind' perspective that have made observers overlook this fact. - 2 - This point, in the present context mostly treated for its theoretical and methodological importance, is the first proposition to be brought out in this paper. do with a reverse phenomenon: A second point has to the tendency to 'politicize' certain key concepts and thus make them practically inoperable in linking theoretical empirical analysis to policy proposals. I am thinking in particular of the term 'interdependence', which is presently being used - purposedly or not - to represent phenomena that are often best analyzed and understood in terms of dominance or imperialism theory. To some extent, the same is true with the use of the dependence concept. I wish to point out certain possible ways of overcoming these patterns of theoretical underdevelopment that follows from the use of dependence terminology for purely political-demagogical purposes. In so doing, I shall make a third point of analysis that relates the notion of a crisis in resource flows during the first part of the 1970s to the question of dependence. As the present paper is part of a much larger ongoing study, I will 2) make my observations in brief. to a (necessary) logical order: They will be made according first, a framework for the analysis of market power is presented; then the problem of dependence is raised; and finally the notion of a crisis and possible changes in the power structure of raw material markets are taken up. Market power and dependence In both economics and politics textbooks, it is rather usual to find a strong bias toward seeing the state as the sole possessor and executor of power to manipulate the market mechanism. Thus, in reporting between-the-wars turmoils in resource markets, even an outstanding political economist like Hirschman sees "national sovereignty over commercial policies" as the main problem (Hirschman, 1945). Once checked, the abuses of trade for power policies would be gotten rid of. Decades before, other analysts had established the firm as a chief actor, operating monopolies or oligopolies in their respective resource markets (Bukharin, 1 9 1 5 ) . Below, some data - 3 - are presented to support the conception that this is at least as true of the present international economy (Table 1 ) . A similar neglect of the basic facts - to which I return is implicit in Bergsten's portraying of the present raw material-producing and -exporting peripheral countries' attempts to associate over their market interests as a 'threat' to the industrialized world, or the center (Bergsten, 1973). The fact that a major share of the supply of raw material originates in the Third World does not mean that a capacity to influence markets, as in a monopoly situation, automatically is there. Geopolitics means, put briefly, that at least political organization is added to space, to the geographical dimension: the location of supply sources. The fact that a small number of firms account for the major share of supply flows internationally (and nationally) is a much more important piece of knowledge in this respect. In order for a raw material commodity to have a value in the market, it will pass through at least the following 'stages': prospection (the identification of its existence and location), extraction or production, marketing, transportation, distribution. Depending on the context in which it appears, it may in addition be refined, further processed, stocked, retransported, redistributed, etc. In this product line, peripheral countries may share in the control at some stage(s). Due to the fact, among others, that these countries historically have been subjected to specializing at the extractive level, been directed to a monopsonistic market (colonial mother-land and/or firm, or sphere of interest) and only recently have started to change this situation through nationalization, going into processing and the like, they find themselves in an asymmetric relationship vis a vis their counterparts, be they transnational firms, big center country governments, or rather both. The firm, more often than not, will share in, sometimes practically exclusively enjoy control at all these stages, because it has integrated operations in all of them in one global organization under one single command. And in addition, it often operates a cartel with other firms in order to regulate whatever controversy, or challenge from third parties, may occur. Table 1. ,~ Concentration in orne selected primary commodity industries and selected areas Commodity IArea (market) . Alum 'niuml } ~vorld IYear Ifirms 6 6 6 4 3 4 1 G"966 1966 19G6' United States 1 1972 United States 1972 1972/73 Japan Bolivia I Zinc 2) Tin 2 ) II li"1 ket share of these firms ln area, 9" NO. of I Copper 2) Lead 2 ) - ,--- Nickell) ; \lJorld -/ Diamonctsl):World Platinum 1) i iHorld ' ,1):\1 Zlrconlu,1l : ·"or 1-'1~ Iron 3 ) 2) Bananas 2) Cocoa Coffee 2 ) Cotton Meat Rubber Sugar Tea Tobacco Rice Vegetable oil J Virtual imonopolies I I '. IUnited States 11970 I ~ 1970-72 .VJorld I )VJorld : France 1969 1969 France 4 United Kingdom! 1971 I United Kingdom' I United Kingdom 'J I United States :1972 IUnited States ;1970 Iworld 11964 (~k:t economies) jGermany F.R. ;196'7 :United States , .197? I World 1969 I , 1 junited KJ,ngdom I 1969 I i United Kingdomi1971 I States !1968 Uni te~ 1 i i IUnited I States !1967 I 3 2 2 5 5 5 4 4 12 3 4 1 1 II i !'. 85 95 75 70 90 70 70 I I Pr:i.nat'y aluminium proc.. Alumina produc'ti.on I Bauxite production Refined copper Lead smelting capacity Zinc sD~ltin~ cap,city (State Corporation) I I I I I (International Nickel Co. ) (de Beers) (Rustenburg) (v.Iah Chang) 54 Raw steel 68 40-60 90 Soluble coffee Processing of green 25 coffe, linported Ground coff.o 60 50 Spindles 25 Looms Processed meat 56 Meat packing 23 New rubber 80 47 65 4 25 43 90-95 46 4 56 3 Level of processing/ production Refining capacity Rice milling 1) H. Hveenl, "The Political Economy of Rm.J Hatcrials", ffilmeo, J'1arch 197~; various so~rc s referred to in the paper. 2) Data collected by the UNCTAD Commodities Division. 3) H. Erdenli & B. Real, L'internationalisation dans la IREP, Grenoble, 1974, mimeo, siderurgie~ - 5 Let us assume, then, that peripheral countries, individually or rather in collusion, move into all (or the most important of) these stages and set up transnational production, marketing and distribution systems, as in particular certain Latin American governments now wish to do. In order to assess the consequences of sucn an eventuality, it is necessary to make a distinction between the various stages of the product line as operational or consequential aspects of world-wide resource flows, and on the other hand the strategic or influential aspects which are technology, information, capital and organization. The present power of firms over global product lines is the result of fargoing past 'mixings' of finance with technological skills, organizational innovation and information to establish operations at those stages which were mentioned. Apart from the recent inroad by the oil-extracting countries into the financial part of the system, there has so far been no successful attempts to take a share of control over others. Nor is the accumulation of an oil surplus by certain OPEC members as yet having any impact in the direction of changing basic processes and structures of allocation of financial power internationally, or reallocating financial capital. These are some important reasons why the percentages of market shares presently held by a small number of firms, practically all originating in big center economies, represent a realistic picture of power structures. Trends towards decon- centration through nationalizations and vertical integration into global product lines by peripheral countries are most prominent in oil, bauxite and copper, extraction and refining. Of approximately 350 cases of peripheral country take-over of a foreign-owned subsidiary in food and raw materials between I960 and 1974 (Un, 1 9 7 4 , a & b ) , a considerable number took place in a handful of countries and involved various forms of take-over, from private local business buying out a foreign owner to full state take-over within an overall strategy of socialization, not all of them representing any real change in power. Both operational and strategic aspects of market power are related to actors: governments. firms, private shareholders, a landowner, I propose, in addition, to introduce the concept - 6 of systemic power, or, rather - since the term 'power' ought to be reserved for actor-related behaviour - systemic aspects of resource market relations. By these I mean given (existing) standards and levels of consumption, development, buying power, etc. that are historically determined and structure present (and future) flows. In other words, the very fact that most of the production of peripheral countries, whether monocultural or not, is marketed in the center economies according to their level of industrialization, resource consumption and economic growth rates, and tastes represents in and by itself an important structural constraint. Dependence and 'interdependence': An attempt at clarifying a theoretical and conceptual mess From the point of view of a center economy - a center-based firm or an industrialized country - dependence on the periphery is first of all a matter of resource imports. Dependence on these areas'as markets for manufactured goods and as labor reserves is, however, increasing. Juxtaposed to this type of unilateral dependence is the dependence of periphery societies on imports of technology, skills, capital and other means of industrial development from the center. And out of two unilateral dependencies, linked to each other as unit A depends on unit B for something and B depends on A for something else and exchange takes place, results accordingly in a situation of bilateral dependence. In the terminology of present-day political rhethoric: 'interdependence'. This simplified view of the world is having its proponents even in scholarly works. It implies that there is equality between A and B; that both parties gain from the exchange because they each trade according to respective comparative advantages and production complementarity; that their respective production factor loadings - or their respective capabilities to improve their comparative advantages - are constant and immobile; that the value of the goods exchanged is set by the market mechanisms; and that they both contribute to and enjoy - 7 a non-conflictuous relationship to the extent they open up for trade and reduce autarkic policies. Because there are also units C, D, etc. which similarly trade with A and B and between themselves, the system is one of multilateral dependence: units are not only directly dependent on other units, but also indirectly. We may retain the distinctions between unilateral, bilateral and multilateral as well as between direct and indirect dependence, as useful analytical tools. It follows from my observations on market power, however, that the content of the 'interdependence' thinking, as represented above, is theoretically unacceptable, or at least problematic. Bilateral dependencies are, as in the center-periphery case, often 'asymmetrical; the equality assumption, thus, is erroneous. Partly because the relationship is asymmetrical at the outset, as e.g. in a relationship resulting from post- (or neo-)colonial rule, gains from trade are unequally distributed (Amln, 1 9 7 4 ) . The assumption of equality, or mutually beneficial exchange, has further been proved wrong by the terms of trade analysis (Prebisch, 1950) and in pointing out the unequal sharing of technology, skills, inter-industry linkages, etc. in a typical center-periphery exchange, that of raw materials against manufactures (Singer, 1 9 5 0 ; Hirscbman, 1 9 6 6 ) . Yet further steps in the critical analysis of international trade has been taken by the 'unequal exchange' theory which points out that unequal sharing of benefits does not primarily take place at the level of nations, but at the level of classes or labor forces (Emmanuel, 1 9 6 9 ) . In the dependencia tradition, finally, a holistic perspective is applied, presenting the dependence relationship as a complex structural-social system and stressing its functional and all-encompassing effects on the local (peripheral) society. The dependencia tradition has been subject to increasing attention outside Latin America in recent years, and some of its basic propositions put to empirical testing. I do not propose to review these efforts in detail here, but confine myself to the following observations. Firstly, many efforts - as pointed out by Cardoso ( 1 9 7 6 ) - do not recognize the fact that dependence theory, as in the Latin American tradition (or, 8 I would say, in general) cannot be reduced to a few propositions that are analyzed totally out of the context of a holistic perspective as that which the theory represents. Secondly, when this is being done, it is quite possible to disprove the proposition of what may be referred to as the school': 'Gunder Frank that growth in the periphery is impossible under conditions of a close relationship of economic interaction with the center. This proposition has been erroneously generalized to be valid for all peripheral areas. Externally dependent growth in the periphery is, thirdly, possible, but it does not (automatically) mean development, since the internal distribution of the gains from growth in the present international system normally will be skewed. Which means, fourthly, that ,the dependence relationship basically is a political-structural one. The 'lucky minority' which does share in growth, through association with the center, performs a maintenance function in the system and guarantees its stability, as far as its power and will to do so goes. Where it stops, or where it shows signs of being weakened from within or threatened from outside, the power of the center is mobilized. This, as we know, may be done in a variety of different ways, from improving the terms of trade of the peripheral country in order to strengthen the local elite (and one's influence on i t ) , to employing such strategic aspects of power as referred to above, or going outside the economic sphere and employing military or diplomatic sanctions - or threats of the same. International relations in raw material markets of the recent decades present numerous illustrations: the US govern- ment agreeing to increase coffee prices in order to strengthen Latin American governments during the Cold War (Howe, 1965); Japanese firms securing raw material supplies through marketing, management and/or export credit contracts with the supplying country; one US firm employing its international financial and organizational strength to pressure the Allende government on the expropriation question (Moran, 197 ); the US government using the military and political guarantee of the United States and her comparative autarchy in energy to bargain a more conciliatory trade policy from her allies-competitors, Japan and the EC (the Federal Republic of Germany) (Knowles, 1 9 7 4 ) . - 9 All this supports the observation that the term 'interdependence' "... for those who wish to maintain United States leadership ... has become the new symbolism, to be used both against economic nationalism at home and assertive challenges abroad" (Bergsten, Keobane and Nye, 1 9 7 6 ) . And it stresses the necessity of analyzing dependence relations in a context of political, military, and general economic factors, not solely in^terms of market relations, even when the various aspects of market power are taken fully into account. Thus, what may be termed single-factor dependence, unilateral or oilateral, of a center unit on raw material sources in a periphery (or in general, an external) area must be analyzed in terms of what probabilities there are that such dependence cannot be controlled for by any of those means which are, or may b e , at the disposal of the center unit. Unit C's vulnerability in raw material markets is, thus, a function of the probability that the conditions for its imports of raw materials from P may be manipulated by P, or by some third unit, without C being able to control against suck an eventuality. Moving to a two-factor dependence relationship, it is a commonly held belief that not only is P dependent on C for its industrialization (importing technology for exporting raw raw materials), but C is dependent on keeping P as a relatively non-industrialized unit in order that P will not become a competitor to C. Such dependence on a 'classical international division of labor' is believed to have led C to actively preventing P from industrializing (the colonial situation) or, if it could not be prevented (completely), to controlling P's industrialization through direct investments or otherwise assuming command of 6) it. Present trends to industrialize P with investments and other forms of assistance from C is not necessarily a disproof of the thesis that C is (to some extent) dependent on the classical international division of labor. The point is not simply to maintain an exchange of raw materials against manufactures, an often too simplistic way of describing the division, but to maintain growth and development inequality. In strict economic terms, for instance, this would mean that - 10 those sectors, or stages of the product line which represent high value added are 'preserved' for C. In more general terms, they represent stages of opportunity for a fuller development, of all the benefits that growth may give to a society and to those living in it.7) This vertical dependence relationship then allows industrialization to take place in P areas, but at lower (subordinate) stages of refining and manufacturing. In addition to the economic and social aspects of vertical dependence, there is the technical aspect, illustrated e.g. by the exclusive use of specific processes in transforming mineral ore into metals and further downstream into first, second stage etc. manufactured goods. Their use is made exclusive through patenting and licensing, aspects of technological dependence. These patterns of vertical dependence represent a system of integration where raw material industries quite often have ceased to be sectors or branches apart and have become more or less integral parts of world-wide manufacturing activities. When, moreover, these vertical structures of dependence are linked to the horizontal structure, that is the spatial dimension, it will be seen for instance that a major US producer of armaments is dependent on a Canada-based firm for some of its secondary metal; this firm takes part of its primary metal from a Norway-based firm which has its refined mineral ore imported from a Caribbean-based smelter. If the various units occupying some task in this structure were independent sellers and buyers, there would have been an intricate network of dependence relations, often approximating bilateral symmetry, often again perhaps giving the P unit, at the bottom of the vertical division of labor, a position of strength. Bilateral and unilateral, direct and indirect cross- country relations of dependence have been assembled and integrated under one roof, that of the transnational firm. The dependence of a number of periphery countries, branches of industry of semi-industrialized or smaller industrialized countries on one or a small number of firms is a more visible, more important pattern than the dependence of the firm on a number of different units, performing their particular functions linked to each other in one product line, but practically non-integrated in terms of bargaining and decision- - 11 - making power. This is 'organized dependence' (Hemes, 1975).' This structural asymmetry - the local affiliates of the firm being ruled, as fragmented units within one system of command - has been subject to increasing attention and concern among the former. There have been moves to form alliances of workers within transnational firms, and as mentioned, there are moves to form associations of producer-exporter countries, the conditions and possibilities of which I am currently investigating. extent They are still a far cry from reaching the of collusion within and among firms. They are also appearing in a situation where firms for long have been conglomerating and diversifying their operations and thus become more difficult to attack according to a material-by-material, or branch-by-branch, approach and with sufficient information about all the intricacies of its operations. In addition, peripheral units are still monocultural and export-oriented and thus strongly dependent on being linked to the world market through a big transnational firm, whether the link is in the form of direct ownership by the firm, a joint venture or minority participation, or a 'simple' trade relationship. Changing dependence patterns? A few empirical observations Monoculturality means, inter alia, that employment and current expenditure are both highly dependent on one product (except for some minerals where production is labor-intensive). Here a tendency towards a decreasingly monocultural production structure in the Third World can be observed, at an aggregate level: Whereas in the period 1 9 5 8 - 6 5 there were as many cases of increasing as of decreasing monocultural production in the periphery nations, between 1965 and 1972 the number of cases (of a total of 77 periphery countries) of decreasing monoculturality was twice that of the opposite pattern 1 7 , 28 showing no change). (32 against In particular, periphery countries specialized in coffee and cotton exports decreased their dependence on these products. At the opposite end, the crude petroleum exporting countries were the main monoculturals'. 9) 'increasingly - 12 On the other side, dependence on imports of raw materials of the 'big center economies on the whole seemed to increase somewhat during the same period. Most of this increase originated in Canada, Australia and South Africa; there has been an overall reduced relative dependence on the periphery, although in absolute terms, in volume, imports to the center have increased radically. As an illustration I have assembled some figures on the United States' import dependence in some basic materials (Table 2 ) . As is well known, Japan is relatively much more importdependent in raw materials than are the United States, while the EC occupies a position in between. At least the following elements seem to have been part of the strategy of Japanese 'firms, backed by the powerful Ministry of Trade and Industry (MITI), during the last decade or so: - to diversify into Australia, South Africa and other resource-rich non-Third World countries; thus, Third World shares in Japanese material imports fell from 90 to 45 percent in the period 1 9 6 5 - 7 4 in the case of iron ore, from 75 to 45 percent for bauxite, and from 75 to 35 for manganese; - in the Third World, Japanese firms to a considerable extent seem to have cashed in on a certain desire to diversify away from excessive dependence on the United States and the EC; - the Japanese firms may have been less concerned with competition from periphery industrialization; as an example, while the US reduced (in relative terms) imports of copper and tin alloys (the very two mineral industries in which the Third World enjoy a considerable smelting and refining capacity), Japan increased hers; the relationship between the firms and the state has been more harmonious and cooperative than in the case of the US, where anti-trust traditions and cross-cutting pressures from industrial lobbies have created more disharmony (Snyder, 1966) (a difference, though, of degree, not a fundamental o n e ) . Irrespective of these trends towards decreased (singlefactor) dependence on imports from the periphery, such - 13 Table 2. Basic (strategic) raw material imports of the United States A: Total imports as a percentage of consumption B: Third World imports as a percentage of total imports 1972 1965 1974 Bauxite 92 100 100 Cobalt 100 n.a. 54 76 71 60 52 l.974 52) 13 Copper (unmanufactured) 16 Iron ore 32 a 49 100 100 100 'Manganese 78 93 78 Petroleum, crude 65 69 Petroleum products 21 SOl) 98 86 Tin 75 Unwrought 100 Alloys 94 100 88 8 Natural rubber Unwrought Alloys C: Defense consumption as a percentage of total consumption in US 7 Tungsten 70 n.a. 65 8 Zinc (unmanufactured) 47 n.a. 30 8 SOURCES: A: Hearings of the Permanent Subcon~ittee on Investigation of the Committee on Government Operations~ United states Senate, Materials Shortages, Part 1, Sept. 1974. B: UN and International Monetary Fund annual statistics. C. Annual Report of the Joint Committee on Defen e Production~ Congress of the United States, 1975, delivered 19 January ]976. 1) Approximate, my estimate. Consists of Residual fuel (63%), Unfinishotl oil (47%), and Distillate fuel oil (10% ~mported). 2) A part is imported as aluminum from notably Canada. 'lor industrialized coun~ries, 14 dependence still exists as long as any amount which represents a difference to firms or to the national economy as a whole has to be imported. What that 'indifference margin' is, will depend on several factors. A public French commission put the margin at which a supplier might have a bargaining option at 30 percent of the total consumption of a buyer (Matteoli, 1975), but the margin in fact could be much lower. In par- ticular, the sensitivity to drops in supply would be great in strategic materials. Take the case of US imports of chromite. There are no important reserves in the US, and current consumption is 100 percent imported: about 40 percent from the USSR, another 30-35 percent from South Africa and Rhodesia. The US government has not applied sanctions on Rhodesian exports of chromite and ferrochromite, no doubt out of concern about this tight dependence on politically sensitive supply lines (although the Rhodesian supplies do not amount to more than a 10 percent of total US consumption). It may be that the apartheid regimes of Southern Africa enjoy some leverage vis á vis the US government due to the dependence of US firms and defense industries on imports of strategic materials, but it may also be that such supplies are what these regimes have to pay in order to have a sympathetic US business and defense community in a world which tries to isolate them politically. In the case of black majority rule, US vulnerability might increase. In view of the fact that considerable imports of strategic materials originate from the main strategic-military adversary, the Soviet Union, and the second main supplier is Southern Africa, there certainly is some concern over import dependence in US government, defense and business circles (Table 3 ) . In its relationship to the Soviet Union, the US government at present probably will have no difficulties in offsetting mineral import dependence against Soviet dependence on imports of US wheat and technology. Or, the dependence that occurs according to a single-factor analysis may be traded against some non-economic factors, such as e.g. Soviet desires to maintain detente, to keep the US from playing too friendly with - 15 - Table 3. ensitive US imports of strategic 1 73 figures Po l'l: ti ca lly materials. Import' as a per cent age of total national consumption Chromite ore Ferrochrome Manganese ore Ferromanganese Antimony 100 Titanium metal Falladium Platinum Vanadium 28 Source: Percentage of total imports originating from (a) South Africa (b) Th & Rhodesia USSR 30-35 35-40 50 n.a. 15-20 40 Ore 110 Metal (China(Taiwan) 20) 33 71 35 51 100 100 41 25 35 35 15 15 60 See source C, Table 2. China, and so on. That is: the dependence is no longer a single- factor bilateral relationship, exchanging minerals for food, but is transformed into (or perhaps originates from) a multi-factor relationship, where political and other factors are added to and influencing the economic one(s). In some respects it may even approach a multilateral relationship to the extent that third parties play a role in determining the form and content of the relationship between the two parties concerned. Dependence relations are seldom stable; they tend to b e , though, under conditions of strong asymmetry as in a colonial or neo-colonial situation. One reason, in addition to those already mentioned, is that there is not one, universal definition of the interest in, the value of a good or an event to all actors concerned. Political, economic and moral con- siderations may give those who influence, or hope to influence, supply lines and dependence margins differing interests. This makes it problematic to define dependence in terms of interests, the value actor A attaches to having a certain material in a given quantity from B. 10) - 16 When we talk about strategic materials, which are 'strategic' because they are considered as 'high interest' goods, we talk about a certain society or a political system, the modern warfare system which means an armaments race which in its turn has led to a colossal and rapidly growing consumption of minerals. With disarmament, one would expect that the 'interest' in, say, titanium would drop. Further, present consumption levels of a good number of other materials are a function of luxury consumption, rapid circulation of goods, in short of overconsuming upper and middle classes in the center. If people e.g. chose massively to not eat excessively instead of trying to slim-fit after having eaten, the interest in soybeans, meat, etc. would similarly drop. What is intended by these remarks is not that an analysis of dependence in terms of interest or value definition is impossible or unfruitful, but that it ought to be properly related to the social goals and position of those whom it concerns; and that it should be dynamic, not static as most analytical efforts so far have tended to be. 11) Aspects of a 'crisis' and some center responses Official government and business concern over sensitive supply lines obviously took a big step in 1973. upward after the OPEC actions Various ways of overcoming dependence on a periphery which was perceived as increasingly uncontrollable were considered. 1. At least five alternative options were brought up: Reduce consumption of materials, and/or more recycling (the ecologist t h e s i s ) ; 2. Concentrate on politically safe areas where resources are still plentiful and organize a joint policy on resource use among the industrialized nations (the IEA strategy); 3. Diversify supply into politically manipulable parts of the periphery, that is countries that are rather unlikely to join the producer-exporter associations; 4. Move into 'non-territories' such as the ocean bed and start mineral extraction from there; 5. Increase use of own national resources (the Independence' strategy). 'Project - 17 - Option 1 does not seem to be taken as seriously in government and business circles at present as it was during the first months after the 'oil crisis'. The Club of Rome studies e.g. presently seem to be more criticized than appreciated for their predictions about resource scarcity. Option 2 is probably more operational, although it takes time before massive new investments in e.g. Australia yield results and the IEA is beginning to function. Option 3 is clearly practized, as for instance shown by the massive new investments in Brazil, Indonesia, etc. 12) Option 4 is behind strong pressures on the US govern- ment to allow or guarantee protection for mineral extraction from the ocean before any international ocean bed regime has been agreed upon. It is believed, however, that the ocean bed resources available (and even sub-economic at present) are much overestimated. Remains option 5. far seems to be a complete failure. 'Project Independence' so There are political, economic and ecological constraints to putting this option into operation, although the latter differ widely: while Japan seems to be bound to import a sizeable share of her material consumption indefinitely, the United States in theory could reduce her dependence on imports considerably. There may be several reasons why this is not being done, including domestic opposition due to fear of pollution, economic reasons and lack of labor force willing to do the job. No doubt, therefore, options 2 and 3 are the preferred ones under present conditions and for the foreseeable future. One of the main reasons why, is of a political nature (I base the suggestion more on logical reasoning than on empirical proof, though): As I have shown above, dependence on imports of raw materials may be offset or controlled for by making the supplier dependent on oneself, politically, militarily, economically. Thus, a leading power unit will establish a number of bilateral relationships based on strategic advantages, with those whom it wants to control. In order to facilitate co-ordination, avoid that some bilateral subordinate get tempted by an alliance with some other subordinates in order to multiply his dependencies, a system of multilateral and multifactor dependence may be a preferred option. - 18 - Such reasoning has been manifest in the policy of the US government with regard to the IFA, and it may be developed further. One possible direction is a combination of options 2 and 3 as in the thoughts of the Vice-Chairman of the US Industry Council, Arthur Harrigan, who in a recent article in National Defense suggested that a constellation of a new type among the capitalist nations might, or should, develop. 13) It would consist of the strongest economies plus those countries with the greatest natural resource potentials and the most advanced means for controlling the flow of resources in the world. This would be the new First World, the purpose of which, according to the author, would be to constitute a sort of 'core area' to the 'Free world', forming a military-political-economic alliance that would be self-sufficient in all vital resources and protect self-sufficiency against communist threats. Members would be the three big - the United States, Japan and Federal Germany - and Canada and Australia among other rich countries, plus South Africa, Brazil, Iran and Saudi Arabia. Together they would control at least 40 percent of world trade and more than 2/3 of all world-wide direct investments; militarily they would constitute an alliance of key areas in all the main regions of the world outside the Socialist world, and no doubt they would represent a formidable resource area. There are trends that indicate that such a capitalist 'core area' is in fact developing. They include a massive US military build-up of Iran; increasing military and economic ties with South Africa; important assistance to technology-weak Saudi Arabia; Australia retreating from the 'resource nationalis of her deposed Labour government; and a joint position of the three big center nations in international negotiations, such as on the UNCTAD raw material programme and the Paris negotiations. An analysis of investment patterns probably would, as I have indicated, show similar trends. But the Harrigan idea also confronts certain major problems. First, it might meet considerable opposition among business interests at home: many big U S , Japanese and West German firms have large investments and trade interests in periphery - and center areas falling outside the 'core area' that - logically - would receive special privileges at the expense of non-core areas and quite probably become monopolized at the expense of 19 a good number of firms. Secondly, even the governments of the three dominant nations would hesitate to divert attention from non-core areas or provoke their hostility for being 'excluded', in such a way that they loose influence. Even a sensitive dependence relation gives opportunities for penetration and control that are too important to be neglected or set aside as 'second class' relationships. One way of solving the problem would be to extend membership, but that would run against a natural interest among the dominant units of the 'core' to keep membership and thereby insecurity due to the possibility of defection, as low as possible. Another way would be to let those periphery areas which are let into the club take on 'sub- imperialist' roles in their respective regions. A third problem would be whether Japan and Federal Germany in fact would agree to such a club that would tend inevitably to be dominated by the United States. I have suggested that certain important aspects of the Japanese strategy after 1973 is not in line with that of the US. Both Japanese and German leaders will have to weigh the advantages of going-it alone in their relations to the resource-rich periphery against (dis)advantages of joining an American umbrella. Even if they cannot establish tight (colonial type) spheres of interest in the periphery, they have shown at least since the mid-1980s that they can compete effectively with the US in world markets at practically all stages of the product line; dependence on US political and military capabilities have not prevented them from doing so. Here, two observations should be made. One is a counter- proposal to what seems to be a widespread view of the postworld war period: that political-military and political-economic questions were separated or otherwise unrelated Keohane and Nye, 1976). They were not. (Bergsten, The United States could create the post-war economic system on the basis of its military strength and unquestioned political leadership of international capitalism, and it enjoyed a leading position in the economicfinancial sphere until the mid-1960s. When Japanese and West European firms then began to challenge US business positions in the most important manufacturing markets, inter alia leading to weakened balance of payments, the US retorted by employing the - 20 - 'latent stick' - its military and financial (monetary) supremacy. The devaluation of the dollar in 1971 was one such weapon, bringing the military guarantee into negotiations on economic questions another. This mounting conflict and the erosion of the monetary system more than any other factors contributed to the 'disturbances' of mineral and raw material markets from 1972 on, and to speculation, buying up of stocks, etc. that sent prices in the marginal (the 'free') markets up. If developments in the energy sector is a valid indicator, the IEA so far seems not to have harmonized policies of the three big. for example, there is tough competition in the marketing of nuclear reactors. And OPEC members to a large extent is approached bilaterally on oil supplies. The 'oil crisis' also brought to the forefront tensions between the state and the firms over price margins, supply policies, etc. I propose that the state-firm relationship in either of the big nations is fundamentally not a very or a 14) permanently conflictuous one. The two are clearly too inter- dependent on each other: intervowen through 'interlocking directorships' or simply common class bclongingness; the state being dependent on the firm for major contributions to balance of payments, to employment, to technology (including that used by the military, by crucial infrastructure, e t c . ) ; the firm is dependent on the state for political-diplomatic and military support, either as between firms pressure or repression. The conflict and states, at the transnational level - such as between the big three referred to - is a more crucial one. Its evolution will probably be the single most important factor in shaping the future of the interantional capitalist system. Is there, thus, a run between contending forces on both sides of the global center-periphery division? If the big three became more split, the 'cere area' became impossible and at the same time the forces forming unity in the periphery grew stronger, present power structures would be changing. If, on the ether hand, OPEC split while the IEA and further on the 'core area' idea worked, there would clearly evolve an even more asymmetrical order. When political, economic tedhnological and ecological aspects are considered in their mutual relationship, chances exist for effective producer associations in - 21 - bauxite, manganese, tin, phosphates, cocoa, tea, hard fibres and some other materials. Time will be a crucial factor and many such associations would improve their chances if they were linked together in order to prevent that firms play one material against another by substituting and/or diversifying. However, political will (in practice, absence of neo-colonial t i e s ) , organizational skill and financial support (by OPEC) that would put an association in a position to sustain a prolonged embargo and/or buyer boycott, are decisive factors, so far mostly lacking. And as Australia's role is rather important to the bauxite exporters and Brazil's decisive to those exporting manganese, prospects do not seem too bright. Present multilateral negotiations - both the.prolonged deliberations under UNCTAD auspices and the dead-locked Paris conference - have a particular importance in this respect. It will most probably not result in any agreement that changes power relations and alters conditions of dependence; it is even highly unlikely that the big center nation governments want such an agreement. This probably means that the negotiations on their part are intended to put brakes on periphery efforts to take other action unilaterally, such as strengthening producer-exporter associations, while the center itself may step up support to their firms' efforts to substitute and diversify supply lines while 'negotiations' continue. This situation where one side alters the context and the conditions of the bargaining setting while the other does not, is nearer to cheating than anything else. The center's experience in 1973 was that it no longer exclusively controlled the capitalist world economy. trying to regain control. It is now The periphery's future will be considerably influenced by what policy OPEC, or individual OPEC members, adopt towards these efforts by the center. Here lies immense conflict potentials, even within the periphery. There is, however, one option which periphery leaders, even so-called 'moderate' or 'nationalist bourgeois' ones, may be increasingly tempted to choose as they realize by the that they are being cheated 'new international economic order' diplomacy: to reduce their dependence on world markets and thereby increase their power and autonomy. In the longer run, an increasing - 22 - disbelief in the virtues of an export-oriented strategy or Bather a general disillusion about the 'Western capitalist model' with its values, development strategy and so on may become a much more serious crisis than anything the center has experienced in the recent past. Notes 1) One indication is the behavior of the research community: during or just after the crises, a great number of reports and comments on raw material suppliers occurred in scholarly journals and books. 2) A monograph is under preparation. Two preliminary and incomplete drafts have been made: "The political economy of raw materials and the conditions for their 'Opecization'", March 1 9 7 5 , mimec. 68 pp. + annexes; and "Producer associations", December 1 9 7 5 , mimco. 91 pp. + annexes. 3) For a further discussion, see Helge Hveem 1 9 7 3 , and my "The technocapital structure and the global dominance system", paper presented at the ECPR Workshop in Strasbourg, April 1 9 7 4 , mimeo. 4) See for instance neo-classical economists as e.g. reflected - in Paul Samuelson's Economies textbook; or 5) Andre Gunder Frank, 1 9 6 7 . An example of empirical testing of the proposition on growth in the periphery is Patrick J. McGowan, "Economic dependence and economic performance in Black Africa", The Journal of Modern African Studies, 14, No. 1 ( 1 9 7 6 ) , pp. 25-40. This example suffers from a lack of appreciation of the wider, contextual character of dependence theory. 6) Hirschman (1945) shows that the Germans before World War II held such a view, even in their policy toward European neighbours; but this view has quite probably been instrumented in British and French colonial policy and in the investment, trade and technology transfer policies of several industrialize countries and firms right up to the present. 7) I am not equating growth and development, nor am I overlooking the obvious negative aspects of modern economic growth patterns with high resource consumption, waste production, etc. that represent aspects of over- or maldevelopment. These, however, are themes which are not taken up in the present context. 8) See footnote 2. 9) This may partly be explained by the important rise in the posted price of crude OPEC oil in 1 9 7 1 , as our data are based on the value of exports. I employed a ± 5% margin of error in order to control for other possible 'accidental' factors affecting the figures. 10) H e m e s , 1 9 7 5 defines A's direct dependence on B as 'the product of A's relative interest in an event and B's share of the control over the event'. p. 60. 11) Similar arguments are put forth by Chouchri and Bennett Commenting on a two-dimensional measure of the importance of individual minerals, one dimension being the centrality of the mineral to the State's economy, the other being the overall availability of it (including political and economic factors): "The most serious difficulty with such assessments , is their static nature. Technological innovations, changes in tastes , interaction between prices and availability, and changes in consumption patterns all interject highly variable effects, the implications of which one difficult to gange. In addition changes in the position of one mineral in the field are inextricably bound with changes in the position of all other minerals." See their "Population, .Resources, and Technology: Political Implications of the Environmental Crisis", International Organization, Vol. 26, no. 2, Spring 1972, p. 198. 12) The stock of direct private investments from the DAC (OECD) countries in Brazil rose from 3728 in 1966 to 6150 million US dollars in 1972, in Indonesia they rose from 254 to 1200 million, according to OECD estimates. The two were in 1972 the single most and the seventh most interesting country for investment in the periphery, respectively. The others from no. 2 to 6, were: Venezuela 3700 millions (3500 in 1 9 6 6 ) , Mexico 2650 (1790), Argentina 2300 (1820), India 1660 (1300) and Panama 1650 (830). After 1972 investments has been rising rapidly in Brazil and Indonesia, whereas at least Venezuela has been disinvesting. 13) National Defense, quoted in Information, Copenhagen 15th July, 1976. Mr. Harrigan is believed to be an unoffical spokerman for the futurologists of Pentagon. 14) For an account of state-firm collusion in France during the 'oil.crisis', see Philippe Simmonot, Let complot petrolier, Paris: Editions Alain Moreau, 1976.