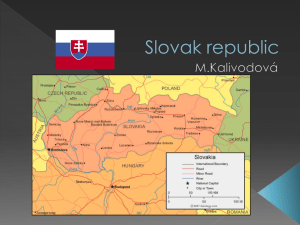

C Thirteen entralism against Slovak autonomism

advertisement