C CC CA A

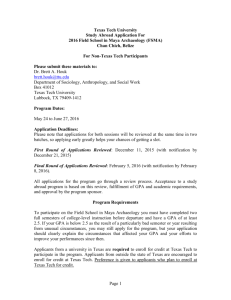

advertisement