Against Assertion

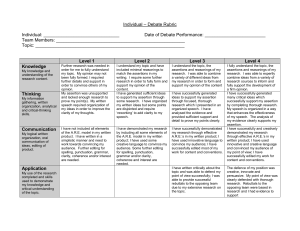

advertisement