DISCUSSION PAPER Playing without Aces: Offsets and the Limits

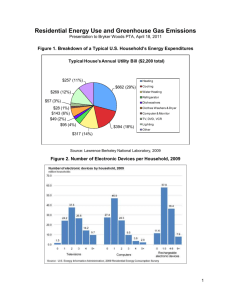

advertisement