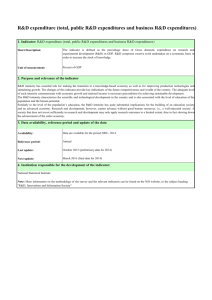

Opening the black box of ... clothing sector.

advertisement